Electronic Games (eGames) in the Language Classroom

Marko Maglic, Germany

Marko Maglic is a teacher of English and Spanish in Cologne, Germany. After finishing his studies in English/Spanish he spent a decade in IT-business. He runs several websites on language learning and teaching and is currently working on his PhD on “Motivation through e-Games”. Homepage: http://www.maglic.de. Email: marko@maglic.de

Menu

Learning vs. playing?

Learning through playing

New paradigms in the digital age

COME-ON games

Conclusion: Online Learning Games – the key to successful learning?

References

While the use of computers in class has been widely examined since they found their way into schools and universities, computer games still have remained in the shadow of scientific research. In contrast to the highly praised didactical value of classical game activities as a teaching and learning method – take for example the enormous success of Rinvolucri’s and Davis’ “Grammar Games” (Rinvolucri, 1984) – pedagogy and psychology have not been hesitating to warn us about the potential dangers of video games. People, observes Prensky, were more or less showered with the “games are evil message” (Prensky, 2006, p. 3).

People playing computer games were those supposed to remain isolated at home, playing some “strange games” and losing their connection to the “real world”. As a consequence, computer games have been considered as being anti-social or anti-communicative for a long time.

Playing games and learning were two different worlds: In times of economic pressure, there is no time for playing games, and even play itself has somehow been banned from the school context for achieving the didactical goals more efficiently. Long time, the common notion was that learning inherently is something that takes efforts, and gaming inherently is something that takes no efforts. So in common sense they didn't mesh up. (Klett, Schulz, & Weingarten, 2008)

Singer’s observation reveals how concepts about play – and thus about games as well as electronic games – have undergone a change in the academic world; play and games are now welcome at school:

From the living room to the classroom, children are being increasingly programmed and structured — as are the teachers who teach them. There is little time for play: the focus is on memorization of the "facts." Indeed, play is viewed as a waste of time when more important "work," the work of memorizing and parroting, could be done. As the pressure on children in school increases, paradoxically their ability to relax and just have fun through play is being restricted. (Singer, Golinkoff, & Hirsh-Pasek, 2006, p. 3)

Playing and gaming are today regarded as an indispensable component of teaching and learning. When electronic games in earlier times had been regarded as somehow anti-social, we here recognise that the new generation of educational games offers new learning possibilities and is intensely social, as Humphreys puts it (Humphreys, 2005, pp. 37–38):

I want to argue, firstly, that computer games are successful because they are more than repurposed "old" media; they are structurally different texts that exploit the multi-directional feedback loops offered by the medium. Computer games draw on their audiences' (players') inputs, require participation, and give feedback and rewards. More recently, with the advent of multiplayer online games, they also exploit the networking aspects of the technology and have thus become intensely social.

As a consequence, play and playing games are seriously being researched as a potential teaching and learning tool. Such intensification of research and the increase of public interest is to lead back mainly to the fact that the “World Wide Web” has altered the way of playing games: People playing games today form communities that simply tear down geographical and cultural frontiers of our societies quicker than anything else before did.

Electronic games (e-Games) have penetrated our daily lives, be it private, business or social contexts. Not surprisingly, the game industry’s turnover has meanwhile exceeded that of the film industry, and as a consequence a profound interest in games and the people who play them has arisen: Industry now carefully analyzes potential markets and puts emphasis on the gamers’ motivation, of course with the intention of increasing profits.

This commercial interest has found its echo in science and – after decades of a scientific concentration on simulations and computer assisted or blended learning – we today can observe an increasing amount of publications on “video games” or computer games: Prensky (2001), Shaffer and Gee (2006), Gee (2008), and many others studied the potential of learning trough electronic games. Steinkuehler (2008) and Malaby (2007) focus on games’ role in and their relation to society.

In spite of the high quality of such studies, they seldom keep pace with the speed of electronic developments: Within the time a book needs from concept to publishing, a new generation of games and players has already emerged. Today, the primary sources for keeping pace with the rapid development of the world of electronic games are the internet and game magazines. Accordingly, research still focuses on the so-called MMPORGs – Massively Multiplayer Online Role Games – when already a new “hype” is waiting at the door: Nintendo’s Wii, Sony’s PS/3 or Microsoft’s xBox have caused a world-wide boom of console games, often pushed into the market as “serious games”, “edutainment” or even “Braintertainment” (Spitzer, Bertram, & Adler, 2007). “Brain Jogging” – in times of increasing demands of economy – seems to be indispensable.

An example of this deep penetration of our lives is that in Germany, since a couple of years, students of year 13 widely use a new motto for the celebration of their “Abitur,” their A-levels: Abitendo – Level 13 completed.

Abitendo – Level 13 completed.

Source: http://abi09.marienschule.de/viewtopic.php?start=105&t=21

At first sight, one might consider this as a kind of retro-like revival of the console games of the 1980s or 90s, but then several decisive aspects would remain disregarded:

- Today’s students – in contrast to earlier generations – are digital natives, formed by the ubiquity of electronic media.

- Gaming has become ubiquitous: Trough the internet we today can play against or with almost everybody, at any time, and everywhere the games we like to play.

- We can form groups – “clans” in the world of the MMPORGs – and thus play together (cooperation) against other groups (competition).

- Online communication has opened another dimension to games, be it in synchronous or asynchronous communication.

- Game developers today know much more about the functioning of the brain, due to the findings of the “Decade of the Brain” (1990s).

- Technological developments have made games extremely fast and realistic, and thus allow a higher grade of immersion.

Learning through electronic games has thus risen to a new “level.”

With this background, new potential dimensions of learning – even at school – have emerged, and according to a study of the LEGO Learning institute, realized in 2002, 94% of the parents agreed that time spent playing is time spent learning (Singer et al., 2006, p. 5).

Two classical questions of pedagogic research have regained importance and, enriched with the game-aspect, are strongly focused in scientific research again:

- Why do people play games?

- How and when do they learn when they play games?

The first question is – with all respect to the abundant outstanding scientific studies – quite easy to answer: People play games because they want to have fun. Their main intention is not to learn, their main intention is to play.

The concept of fun comprises that of immersion and “flow”, a term coined by Csikszentmihalyi which according to Ashley describes a state of mind that should be familiar to any gamer:

Flow, or what an athlete calls being "in the zone," is what happens when other concerns melt away and you find yourself able to concentrate easily on the task at hand, be it saving the world, winning a deathmatch, or clearing as many Tetris lines as possible. Csikszentmihalyi attributes this higher gear of mind power to a perfect meeting of skill and challenge. In other words, it's all about doing something that is neither too easy nor too hard. (Ashley, 2007, p. 68)

We might thus conclude that playing games comes close to – if it is not – an autotelic experience: Once “in” the game, people are driven by intrinsic motivation. The question about how to motivate people to play seems to be meaningless, if we follow Spitzer (2002, p. 192): The question about how to motivate people is [thus] as meaningful as the question: "How do you generate hunger?" The only reasonable answer is "There's no way, as it arises by itself." Accordingly, Spitzer concludes, people are motivated by nature: The system of motivation is always in action, you cannot turn it off, unless you sleep. (ibid.)

Hence the central question game designers have to consider is how to keep people playing, how to attract them and how to keep them in the „flow”: Finding the flow – Ashley resumes, referring to Csikszentmihalyi’s well known book (Csikszentmihalyi, 1997) – is game design's motivational secret (Ashley, 2007, p. 68).

The second question – How and when do they learn when they play games? – has not been answered reliably till today.

We of course are all well aware of the fact that through playing we learn. The playing of children is often an imitation of adults and an indispensable prerequisite for participation in society. This learning effect of what I would like to call “natural playing” is what scientists want to achieve with electronic learning tools when creating simulations or games for educational purposes.

The mistake frequently made is that such ”learning games” often shift the focus from playing to learning, and thus are not able to meet their own demands: If a game is supposed to be enjoyable, the information has to follow game mechanisms – and not vice versa. Effective examples of conventional computer games that communicate knowledge quasi in passing are difficult to find. (Magdans & Gieselmann, p. 89)

The case of a child that is told to play in order to learn illustrates the potential consequences: If the main target was not playing itself – to win, or to lose, or to play with or against others – but the mere learning of new skills, the child would surely regard playing rather stressful than motivating or relaxing.

Not surprisingly, learning games are often considered to be boring:

Learning Games are boring (Schubert, 2008, p. 35).

Such attitude towards not only learning through games, but even to educational software itself is mirrored by the rare use of it. Prior to establishing e-Learning in the Spanish division of my school, I wanted to get to know more about my students’ attitudes towards e-Learning and learning games. In August 2008 I did a questionnaire-based research similar to two other researches I’ve done with pupils of the same age (secondary, year 11/12/13, 16-20 years old students).

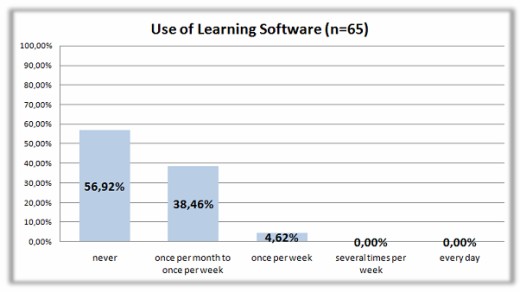

The results of the August resemble those of the earlier studies, revealing that educational software is seldom used by the students:

More than 50% have never worked with educational software or used it, and 38,5% declare that they use it less than once per week. Nobody at all uses it several times per week, what could be called a regular use.

Figure 1: The Use of Learning Software

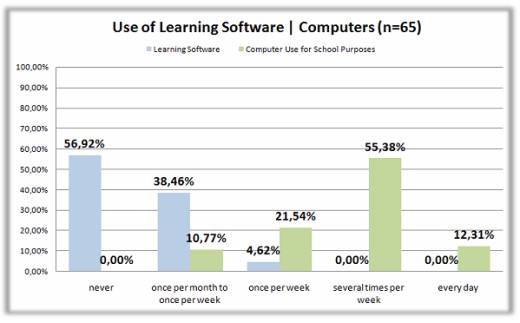

Comparing these figures with the more frequent use of the computer for preparing homework etc. for school, it becomes evident that the development of learning software can by no means be called successful:

Figure 2: The Use of Learning Software | Computers in general for school purposes

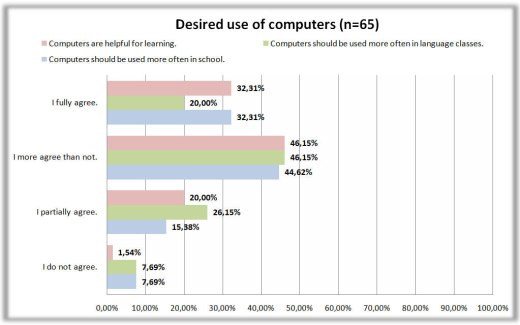

Although computers are not that intensely used for learning purposes, students regard them as helpful and long for using them more often in school: Almost 80% think that computers are helpful for learning and that they should be used more often in class, and around 66% want it to be used more frequently in language classes:

Figure 3: How computers should be used in school according to students.

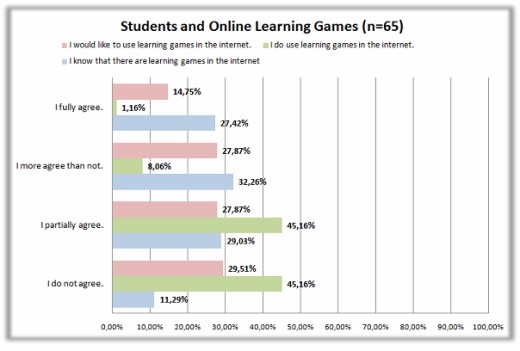

If it comes to games for educational purposes, we can observe that although almost every student knows about browser games in general, only around 40% know about learning games in the internet at all. 9% use them, and more than 40% would like to use („gerne nutzen”) such games:

Figure 4: Students and Online Learning Games.

It thus becomes evident that the failure of learning software – used regularly by not even 5% of the students – could be compensated by games for educational purposes – learning games – which would probably be used by around 42% of the students.

Hence eGames seem to pave the way for a new learning culture which is based on the concepts of „natural” playing. Rüppell calls them COME-ON Games – competitive educational online-games – and explains why they are that interesting for a new concept of teaching and learning in our times:

[...] playing and gaming are self-regulated activities, while learning - in most situations - is fundamentally teacher-regulated. Therefore in order to develop self-regulated learning it may be easier to enrich the self-regulated gaming behaviour with learning activities, rather than to restructure the receptive classroom learning behaviour. (Rüppell, 2005, p. 72)

Consequently eGames, offering the possibility of re-designing class room activities, comply with constructivist and other theories.

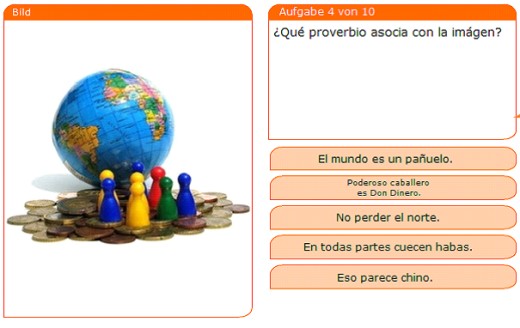

An example of COME-ON games is the internet platform www.studybuddy.de – initiated by Rüppell at the University of Cologne. It offers various game types which students play with or against each other. Immediate feedback is given by the platform in form of points and the correct solution, and is therefore more or less neutral compared to the subjective feedback of teacher or fellow students.

Here, learning is embedded in several types of game activities that the players play with (cooperation) or against (competition) each other. New games can be created by teachers or students, and although learning sequences can be conceived, the players chose the games they want to play through the integrated chat function and invite their “study buddies” electronically to join the game.

Figure 5: Game type “Picture Matching” on www.studybuddy.de

Playing games like the above, the faster or better student gets the points reserved for the correct answer, and thus can „beat” his co-players. The correct solution is displayed a couple of seconds so that each player gets this information and – that’s the key concept of studybuddy – memorizes it better because of the „fun factor”.

Learning is now no longer considered to be „hard work”. Instead, it is fun-based, what meets not only the needs of the students grown up as fast-switching digital natives, but as well enhances cognitive processes within the learners. Kiefer, Schuch, Schenck, & Fiedler (2007, p. 369) propose that

[...] mood states support different encoding processes that contribute to later successful recall. According to the assimilation-accommodation approach (Fiedler, 2001; Fiedler et al., 2003), in good mood stimuli are encoded by transforming incoming information on the basis of stored knowledge structures whereas in bad mood information of stimuli to be encoded is more likely conserved, with no or only minor transformation.

Additionally, the students’ learning process is no longer (directly) teacher-regulated, but predominantly experienced and organised by the students in a way that they become actants themselves. Consequently, a higher engagement is to be expected: The engagement comes because the player is the performer, and the game evaluates the performance (and adapts to it) . (Humphreys, 2005, p. 38)

Hence, evaluation is not reduced to the games’ feedback but enriched by the possibility of direct fellow students’ feedback through synchronous communication tools like a chat function. The nature of COME-ON games is thus not merely competitive, but cooperative at the same time.

The key benefits of eGames like studybuddy, resume Klett et al. (2008), are that such kind of games provide

- involving emotions by utilizing multi player games for intrinsic motivation

- offering various choices in the learning activity to foster processes of self regulation

- offering feedback in many levels to boost cognitive and reflective sequences in the learning process.

Summarizing the above we can assert that contemporary theories – above all neuroscience which generated a new understanding of human learning processes – support the concept of learning through eGames.

The critical point is that till today there is no empirical evidence for the positive effects on learning of these games. On the other hand, is there any reliable evidence for the effects of different learning tools or methods at all? According to my opinion there is not: Studies on these effects often neglect the side effects of the respective tests, and mostly only cover a learning phase limited to a short time span. In case the observed time spans are enlarged, it cannot be guaranteed that the tested students exclusively learn under the test conditions. Who could control whether they do not study at home facing a test situation the next day?

Nevertheless, if not for the scholars – at least for us teachers the most important aspect to be considered should be the motivational, as we day by day ask ourselves how to keep our students motivated for learning. To cope with the new demands of our times, we should look out for new possibilities with open eyes and try them in the classroom, even if the empirical evidence of their effectiveness has not been provided yet:

The world is moving toward an emerging creative class that values conceptual knowledge and original thinking. Ironically, our educational system is going in the opposite direction, as if we were educating children for the 19th century instead of the 21st. Instead of encouraging creativity, thinking outside the box, or colouring outside the lines, we are requiring children to memorize information, even in the face of the fact that information constantly changes. (Singer et al., 2006, p. 6)

The focus has thus to be put to other potential benefits of eGames which for now I would summarize as follows, and which I examine more in detail in my dissertation, to be published in 2010:

- eGames offer new ways of learning which correspond with the needs of the modern learner, who is a digital native.

- eGames provide new possibilities of cooperation, competition and feedback. They shift these elements of learning to a level of ‘playfulness’ that favours positive emotions.

- eGames have a strong motivational power which support the learning process of students that have motivational difficulties with ‘classical’ approaches.

- eGames offer students a new perspective on material, and thus ease understanding and progression.

Ashley, R. (2007). All Work and all Play: How Games are infiltrating the office and powering up the way we work. Electronic Gaming Monthly, (11), 66–70. Retrieved January 12, 2009, from http://www.1up.com/do/feature?cId=3166471.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1997). Finding flow: The psychology of engagement with everyday life. (1. ed.). MasterMinds. New York: BasicBooks.

Gee, J. P. (2008). Video Games and Embodiment. Games and Culture, 3 (3-4), 253–263.

Humphreys, S. (2005). Productive Players - Online Computer Games´ Challenge to Conventional Media Forms. Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies, 2 (1), 37–51.

Kiefer, M., Schuch, S., Schenck, W., & Fiedler, K. (2007). Emotion and memory: Event-related potential indices predictive for subsequent successful memory depend on the emotional mood state. Advances in Cognitive Psychology, 3 (3), 363–373. Retrieved July 18, 2007, from http://www.ac-psych.org/index.php?id=2&rok=2007&issue=3#article_31.

Klett, K., Schulz, L., & Weingarten, D. (2008, September 11). Studybuddy: A new approach to cooperative and competitive online learning: From Teaching to Learning with Serious Games: Making the Case for Multiplayer Online Learning Games. Göteborg. ECER 2008, Main Conference.

Magdans, F., & Gieselmann, H. Schluss mit lustig: Serious Games zwischen Ernst und Spaß. c't (Heise Verlag), 2008(17), 88–89.

Malaby, T. M. (2007). Beyond Play: A New Approach to Games. Games and Culture, 2(2), 95–113.

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital game-based learning. New York, London: McGraw-Hill.

Prensky, M. (2006). "Don't bother me Mom, I'm learning!": How computer and video games are preparing your kids for twenty-first century success and how you can help! (1st ed.). St. Paul Minn.: Paragon House.

Rinvolucri, M. (1984). Grammar games: Cognitive, affective and drama activities for EFL students. Cambridge.

Rüppell, H. (2005). Learning by competition: Compete and optimise your strategy. In R. Carneiro (Ed.), Self-regulated learning in technology enhanced learning environments. Proceedings of the TACONET Conference in Lisbon, Sept. 23, 2005 (pp. 72–78). Aachen: Shaker.

Rüppell, H. (2008). Eine „LAN – Party“ für das Verstehen technischer Dokumente. Retrieved March 06, 2009, from Universität Hamburg: http://www.bwpat.de/ht2008/ft03/rueppell_ft03-ht2008_spezial4.pdf.

Schubert, F. (2008). Daddel Dich schlau? Gehirn & Geist, (9), 32–37.

Shaffer, D. W., & Gee, J. P. (2006). How computer games help children learn. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Singer, D. G., Golinkoff, R. M., & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2006). Why Play = Learning: A Challenge for Parents and Educators. In D. G. Singer, R. M. Golinkoff, & K. Hirsh-Pasek (Eds.), Play=learning. How play motivates and enhances children's cognitive and social-emotional growth (pp. 3–14). Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

Spitzer, M. (2002). Lernen: Gehirnforschung und die Schule des Lebens. Heidelberg: Spektrum Akad. Verl.

Spitzer, M., Bertram, W., & Adler, R. H. (2007). Braintertainment: Expeditionen in die Welt von Geist & Gehirn (1., durchgesehener Nachdruck 2007 der 1. Aufl. 2007). Stuttgart: Schattauer.

Steinkuehler, C. A. (2008). Why game (culture) studies now? Games and Culture, 1 (1), 1–6.

Please check the What’s New in Language Teaching course at Pilgrims website.

|