Some Issues in Teaching English for Specific Purposes (ESP)

Kornelia Choroleeva, Bulgaria

Kornelia Choroleeva is a senior lecturer at the University of Food Technologies, Bulgaria. She is interested in ELT methods, English for Specific Purposes, translation theory and practice, and sociolinguistics.

E-mail: cornelia.choroleeva@gmail.com

Menu

Introduction

Language learners’ needs

Classroom activities

Conclusion

References

Linguists’ acknowledgement of the importance of English language learners’ purposes and needs with respect to the learning process has led to the development of the field of study known as English for Specific Purposes (ESP). Teachers and researchers dealing with ESP are interested in the peculiarities of the English language determined by the profession or branch of science where the language learners will function as second language users. Thus, it is possible to distinguish among English for Law, English for Tourism, Medical English, Business English, etc.

This subdivision of the English language is useful because it draws the attention to the fact that language cannot be taught or mastered in its entirety. That is why, an assertion of the type “I know Spanish” or “I speak perfect Spanish” is not only bold but also utterly fallacious because even native speakers cannot be deemed “to know” their mother tongue. Moreover, languages are not rigid constructs and are constantly subject to change.

The hierarchy of types of Special English presupposes the existence of language variations. Regionally or socially determined language variations are referred to as dialects. Degrees of formality account for stylistic differences. The combination of real-life situations where a language is used is characterized by “a special set of vocabulary (technical terminology) associated with a profession or occupation or other defined social group” [Spolsky: 33] which constitutes a specific jargon. This combination of situations, also termed domain, depends on social factors, namely the place where the interaction takes place, the topic, and the roles assumed by the interactants [ibid.].

Gramley and Pätzold [1992] point out that varieties of English are instances of registers which are classified mainly on the basis of field of discourse and purpose. Fields are determined by situations of use and can be subdivided almost ad infinitum, e.g.: science > natural science > biology > molecular biology, organic biology, cell biology, etc. This means that the boundaries of fields are quite elastic. The classification of Special English founded on purpose gives subtypes such as English for Occupational Purposes and English for Academic Purposes. English for Science and Technology belongs to the latter.

The study of language varieties narrows down the focus of linguistic enquiry, from which both teachers and language learners can benefit. Ideally, by identifying the domain where language is used, e.g.: the home, the workplace, the university, etc., including the social factors mentioned above, teachers will acquire an idea of what to teach and how to teach it. In the case of ESP, it should be kept in mind that Special English, albeit different from the so-called General English in terms of preference of some grammatical structures to others, stylistic characteristics, and field-specific vocabulary, has nevertheless inherited the patterns of word formation, syntactic and discourse organization from the larger system of language. This implies that: 1) the distinction between Special English and General English is not as clear-cut as it seems to be, and 2) the groundwork behind teaching ESP is provided by teaching English as a Second Language (TESL) and as a Foreign Language (TEFL).

All problems stemming from the questions as to what to teach and how to teach it apply both to teaching General English and teaching Special English. The difference is probably in the degree of problematicity. With ESP, these two questions are further complicated. The choice of content relevant to the purposes of learning becomes more difficult to make, partly because language teachers usually do not possess inside knowledge of the profession or science in which the language learners will function as second language users.

The first problem one encounters when teaching ESP is not why their students need English. It might help them to become good computer engineers, for instance. (Although passing examinations is often the only objective.) It is more problematic to find out how students will use English in the relevant setting. If the language learners are university students who go to lectures and seminars in English, they will probably have to develop their listening comprehension skills, they will need practice in writing term papers in English, giving oral presentations in English, etc. If the language learners need English for their present or future job, the teacher should be aware of what this job is supposed to be and what it will most probably entail.

Some authors [Tarone and Yule, 1989] suggest that needs analysis be conducted on the part of the teacher so that “the learners’ purposes in learning the second language” [ibid.: 40] are identified. If this can be done, teachers will know in what situations the learners will need the language as well as what kind of language-related activities are typical of these situations. The concept of “situation”, however, is not easily definable, as Widdowson [1973] points out. Moreover, what is important is to extract those features of the situation which are relevant to the communication process and which govern the choice of certain linguistic elements: “We do not want him [i.e. the language learner] to associate all of the language with just one situation: we want him to recognize which features of the situation are relevant in making particular linguistic elements appropriate ones to use.” [ibid.: 223]. Therefore, it is important to establish those features of the situation functioning as conditions which determine the communicative value of linguistic elements. Broadly speaking, what Widdowson [1973] proposes amounts to the following: 1) utilization of language learners’ existing knowledge, namely knowledge of the formal properties of English and extra-linguistic knowledge embracing knowledge of various sciences, and 2) an extension of language learners’ experience in language, that is in English and in their mother tongue. This means that language learners with some degree of formal instruction in English will be able to transfer what they know of the way their native language is used as a means of communication in science to the foreign language, i.e. to English. In this way, “English structures, previously manipulated as formal objects, can be used to fulfill functions previously only associated with the other language [i.e. the mother tongue]” [Widdowson, 1973: 228].

Needs analysis and the idea of language teaching materials based on linguistic functions, rather than structures, seem to be quite relevant to teaching ESP. However, needs analysis will be more superficial when learners share the same broader field of language usage and use but differ in their specializations. Consider a student specializing in commercial law and a student majoring in international law or two Food Technology students, one specializing in wine and beer production, the other one in the production of bread and baked goods. In both cases, teachers of English will probably stick to those areas of language usage and use which will be of help to both students and which characterize the broader field. This means that other areas will certainly be neglected and this is something teachers and learners are to be aware of.

A related problem is the degree to which ESP teachers are acquainted with the respective science or occupation. Are they aware of the functions bearing communicative value in specialized discourse? Teachers of English are not expected to be experts in every sphere of knowledge but their students do not always understand this. (This is quite applicable to some societies where teachers are perceived as omniscient figures in accordance with the traditional view that they are the ultimate authority in the classroom.) A simple proof is some students’ expectation that language teachers are obliged to know every single word in the dictionary and translate isolated words into and from the foreign language. Similarly, language learners studying Business English, for instance, might expect their teacher to know something about company types and their differences, company management, e-banking, etc. In addition, not all language teachers are acquainted with the linguistic conventions characterizing, let us say, business letters. It turns out that in the ESP classroom it is the language learners who possess the necessary real-world knowledge relevant to the language learning process. It is obvious that English teachers cannot amass all extra-linguistic knowledge they need to design a successful ESP syllabus. The question, which is rather a matter of degree, is evidently unanswerable: What is the minimal knowledge language teachers should have in order to choose content pertinent to the purposes of learning?

The question of field-specific extra-linguistic knowledge also applies to language learners studying some subtype of ESP because it is preferable for them to be at least basically acquainted with the profession or science they need the second language for. If they are university students, it is relevant to decide in which year of their university education they should be enrolled for the ESP course. Otherwise, it may turn out that English classes introduce specialized knowledge before the seminars and lectures in the respective discipline. This is an important decision since it seems that the greater the experience of the language learners in the given science or occupation, the less the pressure on the language teachers to possess a sufficient amount of field-specific knowledge. (Although such knowledge is only an advantage.)

It is obvious that ESP teachers have plenty of issues to address before picking up appropriate teaching materials. When dealing with university students, language teachers sometimes face the problem of designing an ESP syllabus for language learners whose General English proficiency is quite underdeveloped. In some cases, the situation is aggravated by students’ lack of sufficient specialized knowledge. Since language functions as a system, ESP cannot be taught in isolation, i.e. language learners are supposed to be able to communicate in English, however rudimentary their strategic competence may be. Very often the addressees of ESP courses are the so-called English language beginners. Depending on the science or occupation motivating the language learners, teaching ESP to beginners will be feasible in varying degrees. For example, with English language beginners majoring in Cheese Production, the language teacher cannot always use visual aids in the classroom. What kind of picture or photograph will he or she choose in order to elicit “This is whey”, let alone explain what whey is, or make the students identify the parts of cheese-making equipment? The language teacher might opt for an introductory language course first or base the course on an easier-to-grasp general-science content. See, for example, Luizova-Horeva’s [2010] textbook for freshman English language learners majoring in Food Technology and Food Engineering. In view of the students’ different majors, e.g.: Biotechnology, Fermentation Products Technology, Industrial Heat Engineering, etc., as well as their varying communicative abilities in English, the author has opted for a gradual introduction of specialized content:

- Going Places

- Routines

- The University

- Geometrical Shapes

- Measurement and Calculations

- Descriptions

- Objects and Functions

- Actions in Sequence

- Food and Drinks

- Food Preparation Appliances

- History and Inventions

- At the Plant” [Luizova-Horeva, 2010: 3].

Language teachers also have to decide whether they can cooperate with specialists in the relevant fields of knowledge in order to design syllabi. Usually, this will not be possible due to time constraints at least but if it is, such specialists or professionals might help language teachers come up with a number of typical situations characterizing language usage and use in the specific field, complemented by basic jargon and text types, e.g.: memoranda, scientific abstracts, business letters, claims for just satisfaction, etc. Then, language teachers might design an ESP syllabus grounding it on the theoretical framework of a teaching method, e.g.: Total Physical Response, Audiolingual Method, Communicative Language Teaching, etc., or on a combination of several methods, depending on the language learners’ needs.

It should also be pointed out that language learners are not always aware of what they need to learn in the second language. Therefore, it might be more expedient to couple the language learners’ needs analysis with the study of individuals who have already begun to use the second language to communicate in their job or enhance their professional development in the field in which the language learners will need the second language.

Having conducted needs analysis, ESP teachers are to decide what kind of classroom activities are most suitable for the language learners with respect to their age, their present or future career development, their needs and their expectations regarding the learning process. The issue here is whether these activities should be based on a concrete teaching method. If so, which one should the language teacher select as most appropriate? Are innovative methods to be preferred to more traditional ones? It seems that teaching ESP can sometimes follow more downtrodden paths: a language teacher may choose to employ the Grammar Translation method if he or she knows that the language learners will need English not as a means of interpersonal communication but in order to update their professional knowledge by reading specialized literature. However, it might be better to adopt what Tarone and Yule [1989] describe as an eclectic approach. It consists in picking procedures, exercises, and techniques from different methods. This is what is actually done with mixed-ability groups of language learners because language teachers try to make their lessons useful to everybody in class.

Despite the possible disadvantage of devising “a hodgepodge of conflicting classroom activities assembled on whim rather than upon any principled basis” [ibid.: 10], the eclectic approach in ESP classes might not allow the development of one skill or ability to the detriment of another. Moreover, to disregard particular aspects of language usage and use in language teaching is potentially dangerous because language learners’ needs are not fixed or unchangeable. They are fluid and depend on social factors, especially on the roles individuals assume in their everyday lives, e.g.: student, father, computer engineer, etc. It also goes without saying that some skills and abilities are best mastered before or after other skills and abilities, e.g.: one cannot learn how to write business letters in English before learning to read and comprehend simple texts in this language.

Therefore, ESP teaching materials are likely to be more productive when they pay attention to both language usage and language use. According to Widdowson [1978], the former demonstrates the language user’s knowledge of linguistic rules, whereas language use manifests the language user’s ability to communicate effectively. Language use is thus connected with what has been defined as strategic competence: “the ability to transmit information to a listener and correctly interpret information received” together with the ability “to deal with problems which may arise in the transmission of this information” [Tarone and Yule, 1989: 103].

In ESP teaching materials, language usage is reflected in the presentation and drilling of those features considered typical of occupational or scientific discourse: field-specific vocabulary, adherence to certain conventions when structuring and composing written texts and participating in face-to-face interaction, syntactic and morphological constructions which are perceived to appear more frequently in such discourse. As regards EST, classroom activities focusing on language usage usually practice the Passive Voice, modal verbs, conditional sentences, the Simple Present Tense and the Simple Past Tense, the article, Greek and Latin plurals, specific patterns of word formation, etc. [see Gramley and Pätzold, 1992].

To disregard linguistic rules by focusing solely on communicative abilities is dangerous because the language learners might stop paying attention to rules if they think that they can communicate effectively without producing correct and appropriate utterances. Therefore, ESP teaching materials cannot disregard grammar altogether. The question is how linguistic rules should be presented, having in mind that they do not usually have a categorical character but a probabilistic one because more often than not there are exceptions. This is an example of how grammatical rules are traditionally presented: In English, monosyllabic adjectives form the comparative degree by adding –er; small is a monosyllabic adjective; hence, the comparative is smaller. The teacher usually goes on to explain that there are exceptions to the rule, e.g.: the comparative of good is not gooder, as the rule above implies, but better, etc. In turn, the deductive presentation of linguistic usage can be dangerous if it makes language learners arrive at wrong rules. It seems best, then, to present linguistic usage explicitly as regards word formation, syntactic and discourse organization (although with ESP formal knowledge of rules can be practiced in various ways, as will be seen below).

The traditional way of presenting grammar has been widely criticized. See, for instance, Wilkins [in Coulthard, 1992] who raises the question as to how much attention should be paid to grammatical rules and proposes a functional-communicative syllabus based on the following six functions: judgement and evaluation; suasion; argument; rational enquiry and exposition; personal emotions; and emotive relations, each of which is sub classified [ibid.: 151]. Apart from the fact that it is not quite clear what a function is, one might ask oneself why the traditional way of dealing with linguistic usage, i.e. present > drill > practice in context [ibid.: 156], is perceived so inadequate, especially having in mind that so many have studied foreign languages “the old-fashioned way” and have achieved a satisfactory proficiency level.

Some authors, e.g.: Willis [in Coulthard, 1992], point out that some classroom activities such as discussion and role play are considered communicative but they are, in fact, pseudo-communicative. Subsumed under simulation, such activities are compared with replication ones, e.g.: solving problems or playing games, which are thought to create situations “in which there is a real need for communication in order to achieve something else” [ibid.: 158]. The so-called citation activities like repeating, combining, and transforming [ibid.: 157] are suggested as the second step in the learning process consisting in the sequence replication > citation > simulation [ibid.: 158], the stage at which certain linguistic items are taught explicitly and then practiced in simulation exercises. As an example is given a replication exercise “concerned with distinguishing and matching shapes” which “will naturally lead into citation exercises concerned with the specific lexis of size and shape and the grammar of nominal group structure” [Willis in Coulthard, 1992: 159].

Along these lines of thought, one wonders if it is at all possible to devise ESP classroom activities which imitate closely real-life communication. This cannot happen simply because these activities will be performed in the classroom. Teachers are unlikely to possess so much time and resources to be able to take their students to business meetings, production plants, chemistry laboratories, etc. in order to “plunge” them in real-life situations and monitor they way they communicate. In addition, the very presence of the teacher suggests artificiality.

It also seems that simulation exercises are useful in ESP classes and are interesting to language learners. Provided that the teacher manages to control the topic, he or she may witness heated discussions in which students express a few of the functions Wilkins talks about. For law students, for example, it will be helpful to participate in mock trials in English for the same reason. Language learners forget the artificiality of the communication task if it is in accordance with their real-life interests. In this case, classroom activities will have a communicative outcome and will be brought closer to real-life situations.

The replication/citation/simulation sequence might prove to be suitable for some ESP classes, especially with some types of replication activities, as in Willis’s example, but it is unclear whether language teachers can apply replication exercises to everything they want to teach and with every language learner. If for various reasons the language learners do not have the capacity to perform the replication activity, e.g.: solve a mathematical problem, it will not lead “naturally” to the citation exercise introducing the lexis of mathematical operations. Language teachers might also face greater difficulties thinking of replication activities for mixed-ability groups of learners or a class of professionals working for the same company, in the same branch of industry, who do not share the same occupation.

It might be better to envisage a compromise via which language learners’ needs and expectations coupled with the purposes of each individual lesson will determine whether citation, replication, or simulation activities will be used. Certain aspects of grammar or communication might go well with specific types of activities. Coulthard [1992] makes a point that greetings, closings, invitations, and presequences can only be practiced through simulation. The communicative value of citation activities like transformation exercises, e.g.: turning sentences from Active into Passive Voice, and conversion exercises, e.g.: changing tenses, can be manifested by their contextualization. This appears to be applicable to teaching ESP, especially EST, because citation activities can be used to teach language learners to create various kinds of discourse units. Widdowson [1978], for example, talks about a procedure called gradual approximation consisting in the development of a series of simple accounts, considered to be genuine instances of discourse, their complexity gradually increasing. One of Widdowson’s suggestions is this:

- the language learner is asked to do a completion exercise, e.g.: a sequence of topic-related sentences with present-tense forms of verbs to be provided; the sentences can be based on diagrammatically presented information such as a chart;

- the language learner is asked to do a transformation exercise, e.g.: combine the completed sentences in pairs, one of them becoming relative clause;

- the language learner is asked to create a simple account, i.e. arrange the sentences into a paragraph [ibid.]. Gradual approximation can be useful in ESP classes because it is based on a linguistic and a non-linguistic source of information, the former showing the language learner the linguistic usage and the latter the communicative context of the activity.

In teaching ESP, it seems that most motivating and productive is the strategy to use visual aids when possible because they invoke associations with the extra-linguistic reality determining the language learners’ needs to study Special English. Such exercises may necessitate extra-linguistic knowledge and will thus be less artificial communicatively if one follows the scale of artificiality mentioned above with reference to citation, replication, and simulation classroom activities. Visual aids include maps, tables, formulae, various types of charts, and pictures and photographs of objects, apparatus, etc. These are especially useful when teaching EST because they constitute some of the most typical means of presenting and organizing information in written scientific discourse. Here are some suggestions as to how to use visual aids in the ESP classroom.

Arranging terms in tables can be used to elicit vocabulary items and can be combined with the presentation of new lexis. For instance, the headings of the table columns may denote qualities of foods and learners may be encouraged to think of meals and drinks possessing these qualities. The activity can be combined with practice of the structures “I dislike/hate/detest/loathe/can’t stand… because it is (not)…” and “I like/love/adore…because it is (not)…”, e.g.:

| lumpy |

chewy |

fizzy |

sour |

spicy |

rank |

| cottage |

cheese sweets |

beer |

lemon |

curry |

butter |

| ... |

... |

... |

... |

... |

... |

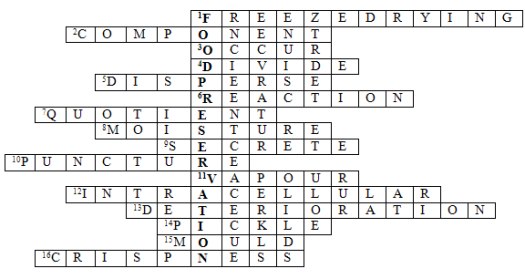

Doing crossword puzzles may be used to recall definitions and specialized vocabulary. Crosswords refer to extra-linguistic knowledge and practice spelling. Here is an example of a task in which learners have to fill in the crossword in the way it is shown below:

“IV. Do the following crossword puzzle with words from the text.

Horizontally:

- lyophilisation, a method of drying in which the material is frozen and subjected to high vacuum (n.)

- a synonym of “constituent” (n.)

- a synonym of “appear” (v.)

- the verb denoting the mathematical operation in 4 : 2 = 2 (v.)

- scatter, spread; cause particles to separate uniformly throughout a solid, liquid, or gas (v.)

- the mutual influence of chemical agents (n.)

- the result of division; the number of times one quantity is contained in another (n.)

- water content, wetness (n.)

- release by secretion (v.)

- make a hole, pierce, perforate (v.)

- the result of water evaporation (n.)

- existing within the cell (adj.)

- spoilage, e.g.: of food (n.)

- immerse foods in salty solutions to protect them from spoilage (v.)

- minute fungi on vegetable or animal matter (n.)

- the quality of being hard and easily breakable, the opposite of being soft and wilted (n.)

Vertically: 1. You will get the group of methods protecting food from spoilage.” [Choroleeva, 2009: 16, 17].

Alternatively, learners may be asked to create their own crosswords for other learners to solve.

Drawing can be used to practice defining concepts or objects and to check listening or reading comprehension skills. For example, language learners may be asked to draw the object on the basis of the definition they hear or read, e.g.: This is a cone-shaped utensil with a tube at one end, or they may be given a picture or a photograph of the object in order to give a definition. In both cases, there is a non-verbal presentation of information and a transition from verbal to non-verbal mode or vice versa, a procedure Widdowson [1978] calls information transfer. Information transfer develops comprehension and interpreting when it is oriented from verbal to non-verbal mode; in the reverse direction, it practices writing and composing. Here is another example practicing lexis denoting shapes and location:

“Read this description and draw the diagram which it describes:

At the top of the diagram there are two horizontal parallel straight lines. At the bottom there is a horizontal spiral. In the middle there is a circle. On each side of the diagram there is a cross. There are two inverted triangles diagonally above the circle, one on the left, the other on the right. The triangles are below the parallel lines. In each triangle there is a dot. Above the spiral and below the circle there is a square.” [Bates and Dudley-Evans, 1976: 30].

Pictures or photographs can be used for learners to label constituent parts of apparatus and various objects or provide descriptions. Widdowson [1973] suggests an activity in which a specialized text is accompanied by an unlabelled diagram. The teacher may ask the class to read the text and label the diagram, i.e. transfer information from the text to the diagram, in order to check the learners’ reading comprehension skills.

Tarone and Yule [1989] offer another example of how language teachers can use pictures and photographs: “The speaker sees only one object (on video or in a photograph) and is instructed to describe that object so that the listener can identify the object from a set of similar objects.

The listener has a set of three photographs, labeled A, B, and C, and, following the speaker’s description, has to choose which one of the photographed objects is being described” [ibid.: 181].

Another option is to use pictures and photographs to illustrate sequences of events, as in “Read how the Tay Bridge collapsed. Match the sentences (1-5) with the diagrams (a-e) below” [White, 2003: 23]. Tarone and Yule [1989] suggest a task in which a language learner watches on video (or on the computer) how a process, such as the assembly of a piece of equipment, is being carried out and then has to give an account of the process for another learner. The latter is shown a set of several photographs related to the process. Some of the photographs depict stages in the process, others do not. The second language learner, being the listener in this task, has to choose only those photographs which are relevant to the described process.

Maps and various types of charts can be used to check the language learners’ comprehension skills, to practice numbers, decimals, etc. The teacher may ask learners to read a text or a set of sentences on the basis of which they have to draw a map or label a chart. For example, learners might be given the following text titled Population:

“There were twelve point one million children aged under sixteen in two thousand: six point two million boys and five point nine million girls. This is fewer than in nineteen seventy-one, when there were fourteen point three million children. In two thousand, thirty per cent of children in the UK were under five, thirty-two per cent were aged five to nine years and thirty-eight per cent were aged ten to fifteen. These proportions were similar in the nineteen seventies.”

[White, 2003: 29]. The learners then have to label a bar chart showing the number of children in the UK in the respective years and a pie-chart illustrating the proportion of children in different age groups.

Concerning specialized terminology, language teachers must be aware that some terms are used in several fields of science and contextual presentation of sense, rather than dictionary meaning, is preferable. Also, it is easier to study vocabulary in context, not in isolation. Specialized terminology tends to be standardized and clear, not vague, which means that terms can be translated into the native language, so that no room is left for ambiguity.

Specialized and “catchy” vocabulary can be presented, for example, via sentence pairs. If the language learners are students majoring in Milk and Dairy Products Technology, the teacher might present them with a set of sentences contextualizing some terms and ask the students to tick those sentences where the terms are applicable in this sense to the production of cheese, e.g.:

- Egyptians were the first to knit items of clothing: among the earliest known examples are colourful wool fragments and cotton socks.

- Lager beers usually take more time to brew and are aged longer than ales.

- The Professor invited me into his office to clarify why my term paper had received a bad mark.

- I will miss the starter and order the main meal instead because I am starving.

- Moulds are fungi used in the production of bread and wine.

The sentences in which the italicized terms are used in a sense in which they will most probably appear when talking about cheese production are 2 and 5: some cheeses are aged and some cheeses have a mouldy rind. After that, the students might be asked to read another set of sentences where all of the italicized terms are used in the context of cheese production, e.g.:

- After being drained, the curds are allowed to knit so that the desired cheese moisture and texture can be achieved.

- The hydrolysis of protein during ageing contributes to the development of a softer body and aromatic flavour of cheese.

- Milk is clarified because in this way extraneous matter can be removed and the texture and flavour of the cheese will be improved.

- A starter (culture) of lactic acid-producing bacteria is added to warm milk.

- Blue cheeses like Roquefort are produced by adding the Penicillium mould to the curd or by injecting it into the cheese.

The second set of sentences is compared with the first one, in which the italicized terms in examples 1, 3 and 4 were used in a sense irrelevant to the context of cheese production. The second set of sentences may be presented in the form of jumbled phrases to be arranged. The students might then be asked to put the sentences in the order in which the respective stages in the manufacture of cheese will appear. The correct order of the sentences is 3, 4, 1, 5, and 2, i.e. milk clarification, addition of starter culture, knitting of curds, addition of mould, and ageing of cheese. The students may also be asked to think of the missing steps in cheese preparation, which in this case will be cutting, cooking, salting, and pressing the curds. (Draining is mentioned in sentence 1.) In this way, the teacher will introduce the unfamiliar terms by making the students use their extra-linguistic knowledge.

In summary, teaching ESP is inspired by teaching EFL and ESL but the peculiarities of the various types of Special English may give rise to great many approaches to the learning process, especially having in mind the fluid needs of the language learners. The problematic aspects of teaching ESP may come from:

- the teachers’ insufficient extra-linguistic knowledge relevant to the learning process which may be accompanied by their insufficient awareness of the functions having communicative value in specialized discourse;

- the language learners’ insufficient strategic competence in General English which may be accompanied with insufficient extra-linguistic knowledge relevant to the learning process;

- the lack of adequate teaching materials in ESP and the necessity to design a needs-oriented ESP syllabus;

- the choice of field-oriented content in the teaching materials;

- the selection of appropriate classroom activities;

- the necessity to pick up teaching materials suitable for mixed-ability groups of learners as well as for groups of learners with different individual needs.

Notwithstanding the problems mentioned above, one hopes that applied linguists’ insights and the undiminished motivation of teachers and language learners will contribute to the enhancement of ESP teaching methodologies because learning language is always learning with a purpose.

Bates M., T. Dudley-Evans, (1976) Nucleus. English for Science and Technology. General Science, Longman

Choroleeva K., (2009) English for Food Science, UFT Academic Publishing House, Plovdiv

Coulthard M., (1992) An Introduction to Discourse Analysis, Longman

Gramley S., K. Pätzold, (1992) A Survey of Modern English, Routledge

Luizova-Horeva T., (2010) English for Technology and Engineering Students at the UFT, UFT Academic Publishing House, Plovdiv

Spolsky B., (1998) Sociolinguistics, OUP

Tarone E., G. Yule, (1989) Focus on the Language Learner. Approaches to Identifying and Meeting the Needs of Second Language Learners, OUP

White L., (2003) Engineering Workshop, OUP

Widdowson H. G., (1973) An Applied Linguistic Approach to Discourse Analysis, unpublished PhD thesis, at

www.teachingenglish.org.uk

Widdowson H. G., (1978) Teaching Language as Communication, OUP

Please check the CLIL: Content and Methodology for Secondary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the CLIL Materials Development ( Advanced Level) course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

|