Videoconferencing in English for Law Courses: Cooperation and Politeness Principles Revisited

Alena Hradilová, Czech Republic

Alena Hradilová is responsible for studies and quality of education at Masaryk University Language Centre, Brno, Czech Republic and is based at the Language Centre’s Department at the Faculty of Law where she specializes in teaching English for law. Her broad academic and teacher training experience covers mainly the use of videoconferencing technology in teaching ESP and EAP, teaching academic writing, soft skills and the use of hedging in scientific writing.

Menu

Introduction

Background

Method

Results

Application of results

Conclusion

References

Appendix

This article deals with a case study of a videoconference (VC) course held jointly between law students from Masaryk University, Czech Republic and law students from the University of Helsinki, Finland. A corpus of video recordings of VC sessions was collected over a period of four semesters in order to analyse situations where non-observance of Grice’s Cooperative Principle and/or Leech’s Politeness Maxims interferes with or completely disables the flow of communication between students. The aim is to explain why attention to certain pragmatic issues in teaching English via videoconferencing has been identified as important. Results of this case study are applied to teaching methodology and implemented into the course structure.

Videoconferencing as a part of a language course has become a traditional means to humanize language teaching at Masaryk University (MU) Language Centre (LC). MU LC team, together with language teachers from Aberystwyth University, Great Britain, developed a teaching methodology and various guides for both teachers intending to use videoconferencing as a part of their course as well as for students who are exposed to the new (videoconferencing) learning situation (see Invite project 2006-2008, Morgan et al. 2007, Hradilová and Štěpánek 2007, Budíková et al. 2008, Hradilová et al. 2008, Štěpánek and Hradilová 2008, Hradilová, Chovancová and Vincent 2012). In our particular situation, “videoconferencig” involves mainly joint courses, where two geographically distant groups of students meet regularly via a videoconference format. These virtual meetings reflect students’ need for authentic communication and cross-cultural situations as well as students´ future needs as skilled employees.

The know-how has been adopted by other European universities (see e.g. Denksteinová and Podlásková 2013). Other research in the field of videoconferencing, based mostly on a one-to-one teaching situation, also takes place outside Europe (Anastasiades 2010, Hopper 2014).

This article describes a case study of a course held jointly between law students from Masaryk University, Czech Republic, and law students from the University of Helsinki, Finland. It addresses pragmatic issues in student communication which have been identified as problematic, in need of analysis, application for teaching methodology and course materials, and attention in videoconferencing English language classes. For this purpose, a corpus of video recordings of videoconference sessions was collected over the period of four semesters to be used to analyse pragmatic issues. Emphasis is put on situations where non-observance of Grice’s Cooperative Principle or Leech’s “politeness maxims” interferes with or completely disables the flow of communication among students. It is argued that these issues partly result from differences between the cultures (Czech, Finish and English), and also from students level of language competence in English, according to Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR), where students oscillate between B2 and C1 levels.

The pragmatic issues identified as problematic in the corpus seem to be connected to politeness and flow of communication, which is why it is worthwhile revisiting Grice’s Cooperative Principle (the basic Maxims of Quality, Quantity, Relation and Manner) to use as the bases for the analyses. Nevertheless, as the issues in communication seem to be more complicated, I am looking further into Grice: “there are, of course, all sorts of other maxims (aesthetic, social, or moral in character), such ae “Be polite (…)” Grice (1991: 28). Students might think they are being polite as their native languages may require realization of other language patterns in order to fulfil their cultural Politeness Principles (cf. Suszczyńska 1999).

Politeness in English has been the centre of attention since the late 1970’s (e.g. Borkin and Reinhart 1978, Brown and Levinson 1987, Fraser 1990). Studies of language strategies used by non-native speakers of English compared to native speakers prove differences in speech acts especially at the level of formality and directness, for example in making requests (confront Wierzbicka 1991, 1985). A detailed analysis of cross-cultural data by Suszczyńska (1999: 1064) concentrating on speech acts and strategies of native speakers of English, Hungarian and Polish confirmed that while Anglo-American culture avoids “direct confrontation”, Polish and Hungarian culture tends to be “confrontational” and “direct behaviour is not discouraged, and opinions and emotions, including negative ones, can be expressed in strong terms, even if painful for the other party” (Suszczyńska 1999: 1064). I am assuming that these findings could be applied to Czech language speakers as well, as parallels with the results of her study correspond to the small scale research results presented here.

This is why some basic principles of politeness, namely Leech’s Politeness Principle Maxims (the Maxims of Tact, Generosity, Approbation, Modesty, Agreement and Sympathy) were added to the Maxims proposed by Grice in order to analyse the problematic situations in students’ communication and in order to practice these principles with students. As Leech states, the students need “to solve the problem: ‘Given that I want to bring about such-and-such result in the hearer’s consciousness, what is the best way to accomplish this aim by using language?’” Leech (1983: X).

A corpus consisting of 24 hours of video recordings was collected for future analyses during the videoconferencing sessions over the period of two years. Four different groups consisting of approximately 20 Czech and Finish students per group were involved. The total number of students in the sample was 78; 43 Czech and 35 Finish students.

Situations where the flow of conversation decelerated or even stopped were identified and transcripts of these conversational exchanges were made and grouped according to the cause of the problem in communication. For this purpose, Grice (1991) and Leech’s (1983) pragmatic theories were revisited in order to label the categories (i.e. the Maxims that had been flouted). Grice’s Cooperative Principle offers the Maxims of Quality, Quantity, Relation and Manner. Leech enriches the scale with Politeness Principle and offers the Maxims of Tact, Generosity, Approbation, Modesty, Agreement and Sympathy. Each of the situations that were identified as problematic in students’ communication was compared against these checklists of Maxims in order to identify whether a particular breech of a Maxim or Maxims led to the communication problem.

These findings were then applied to the teaching-via-videoconferencing methodology. A set of exercises, based on real situations from the corpus, was developed in order to raise students’ awareness of the issues and teach soft skills that would help students to perform efficiently and with respect to what they identify as good practice in conversation with their particular foreign counterparts.

Differences in approaching the communicative situation are noticeable in the corpus. This seems to be a general principle, whether in everyday life of the united Europe (Doughty 2012) or in the videoconferencing classroom in this study. Our videoconferencing classroom lacks students who are native speakers of English. It can be seen, however, that students who reach a C1 level (CEFR) tend to observe native-speaker-like politeness principles. We have noticed that they are more likely to exhibit intolerance towards their less polite classmates (see example of good practice – Ex. 11). This is not surprising, as CEFR descriptors for an even lower, i.e. B2 level require that a B2 speaker “can sustain relationships with native speakers without unintentionally amusing or irritating them or requiring them to behave other than they would with a native speaker”. Being duly polite is a part of such a request. It is, therefore, my belief that students at B2–C1 CEFR need to pay attention to learning these principles in order to reach the required pragmatic level of English.

As a next step, the individual problematic situations that have been identified in the corpus are grouped according to the issues in question (see examples 1–10 below) and compared against the checklist of Grice’s and Leech’s Maxims. The following Maxims have been identified as flouted and therefore important for the application into methodology:

Grice’s Maxims: Quality, Quantity, Relation and Manner

Leech’s Maxims: Tact and Sympathy.

The examples 1–10 below illustrate situations or groups of reoccurring situations that led to a problem in communication. Each of these examples is followed by a list of Maxims which were flouted:

- Situations grouped under the heading “strategies in civil disputes”

Maxim of Quantity (“make your contribution as informative as required; do not make your contribution more informative than required”).

Tact Maxim (“choose structures that increase politeness by using a more indirect kind of illocution”).

Sympathy Maxim (“be sympathetic; minimize antipathy between self and other”).

It is essential for students to realize that while negotiating a civil dispute, they are expected to choose their strategies with empathy. Both Czech and Finish students tended to be either too brief and omitted necessary metalanguage or, on the contrary, prepared lengthy speeches which were difficult to follow. Moreover, some of them were not aware of the fact that polite, formal English requires indirect expressions rather than directness, which is often viewed as patronising and rude. It was also noticeable that some of the students found it difficult to strike the balance between confidence and arrogance.

- Ex.: Prosecutor: Your honour, can I introduce my last witness? – Judge: Well, if you want to…

Maxim of Quantity (“make your contribution as informative as required”).

Sympathy Maxim (“minimize antipathy between self and other”).

In this example, the student performing the role of the judge uttered a phrase which was inappropriate in his position. A judge is expected to exhibit his control over the proceedings and state his directions clearly, refraining from colloquial and vague phrases. Such utterance could also be perceived as disrespectful by the prosecutor in question.

- Ex.: A prosecutor addressing the judge: OK, sorry… [a few seconds silence] … your honour!

Maxim of Quantity (“make your contribution as informative as required”).

Sympathy Maxim (“minimize antipathy between self and other”).

This is another example of an utterance where the student should have been aware of the necessity to be formal, polite and to speak in full sentences in order to show respect to his/her counterpart.

- Ex.: Judge: Would you like to swear on the Bible or make an affirmation? – Witness: Yeah!

Maxim of Quantity (“make your contribution as informative as required”).

Maxim of Relation (“be relevant”).

Sympathy Maxim (“minimize antipathy between self and other”).

In this situation, we can identify two major problems. First, it is the lack of comprehension on the part of the witness. Secondly, it is his tendency to speak too informally for the setting. The first problem leads to his brief, irrelevant answer, the second to his choice of a colloquial expression.

- Situations grouped under the heading “reference to an ethnical minority”

Maxim of Relation (“be relevant”).

Sympathy Maxim (“minimize antipathy between self and other”).

This seemed to be a reoccurring problem typical of Czech students, exclusively. Some Czech students made references to stereotypes concerning a certain ethnical minority without understanding that not only was the stereotype not shared by the Finish group, but it was also considered inappropriate to make such references.

- Situations grouped under the heading “a student asks a question, his foreign counterpart does not understand/misinterprets/ignores the question and continues talking about something else or changes the subject”

Maxim of Relation (“be relevant”).

- Situations grouped under the heading “making up evidence and proofs “

Maxim of Quality (“do not say that for which you lack adequate evidence, do not say what you believe to be false”).

Sympathy Maxim (“minimize antipathy between self and other”).

In some cases, students decided to be more creative than required and, in order to win a case, introduced “new” evidence. This may not be a problem if both parties agree that these are the rules of the game. In other cases, however, this may bring mistrust and create an obstacle in communication.

- Ex.: Students opening a discussion over a summary they were supposed to read and comment on: We have a problem with your piece of writing. There is no information in it!

The Tact Maxim (“choose structures that increase politeness by using a more indirect kind of illocution”).

The students should have used an introductory sentence here. Moreover, a less direct expression to criticize their foreign counterparts was expected. This opening proved to be devastating for future communication.

- Situations grouped under the heading “negotiating meaning of words” – Ex.: an abandoned house (see a full transcript of the example in the Appendix).

Maxim of Manner (“avoid ambiguity of expression”).

This is an example of a semantic issue where the students need to negotiate their perception of notions in order to maintain communication.

- Situations grouped under the heading “pre-prepared speeches”

Maxim of Manner (“be brief”).

When preparing speeches, students generally tended to prepare lengthy speeches, which were difficult to follow in the videoconferencing environment.

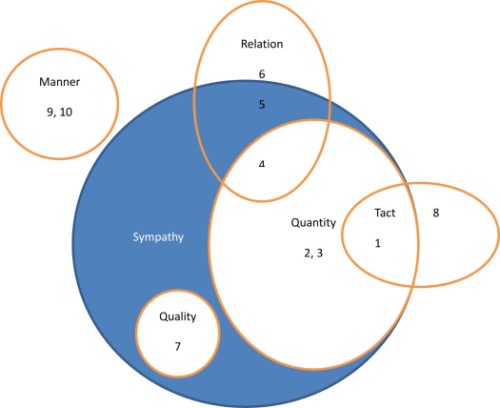

These results can be graphically illustrated as follows:

Figure 1: Distribution of problematic situations related to Grice’s and Leech’s Maxims

Figure 1 illustrates sets of the identified problematic situations. Each of the sets is labelled according to the Maxims in question. The numbers in Figure 1 refer to the situations and examples (1–10) listed above Figure 1. In six cases, I found a combination of breeches of the Principles while four of the examples stand on their own, flouting just one of the Principles.

There are also other situations in students’ conversation where Maxims are breeched, intentionally. These are examples of irony or sarcasm which in the context of a student group serve as conversation boosters rather than stoppers. The following situation where the judge addresses the prosecutor by her real name rather than the fictional one from a role-play can serve as an example.

- Ex.: Prosecutor: If I may, your honour, it’s miss King. Thank you… [the prosecutor bows], your honour.

In this case, the Tact Maxim was flouted by using an overpolite expression in the given situation (i.e. a group of students). The expression was thus perceived as sarcastic. Here, it is important to remember, that “politeness is essentially asymmetrical: what is polite with respect to hearer or to some third party will be impolite with respect to speaker, and vice versa” (Leech 1983:107). It was, nevertheless, praised as “very clever” in the follow-up discussion with the students.

The following section offers some teaching strategies and types of exercises which were incorporated into the course syllabus in order to address student behaviour in the above mentioned situations. The aim is to raise student awareness of the aforementioned issues and provide for good practice. In order to illustrate the point, this section describes the course syllabus, how it was changed and what particular exercises based on authentic situations from the corpus were included into the course materials in order to help students overcome the problematic situations mentioned above.

In this case study, I apply the results to a course designed specifically for students of legal English. There are usually five virtual meetings planned for the students to perform given tasks in an international videoconference environment. The rest of the semester work (i.e. seven sessions) is dedicated to both preparations for the virtual meetings, as well as to other English for law work which is specified in the course syllabus. In other words, the course is not designed to be fully delivered by videoconference. Videoconferencing is, rather, integrated into the general course syllabus to suit both parties involved (MU and University of Helsinki law students) and to add authenticity to the real-life-like situations of student communication. Both student groups are otherwise monolingual and any discussion performed in English is viewed as artificial. In international videoconferencing, using English is often the only logical and practical option. The course is thus built on three main pillars: preparation for videoconferencing, videoconferencing meetings and other English for law work.

It is important for students to be introduced to the idea of videoconferencing before the first virtual meeting with their foreign peers. So far, a hundred percent of MU course participants claimed they had no previous experience with videoconferencing set-ups, except for Skype calls. This is why our team developed a set of exercises that can be used prior to the first VC (cf. e.g. Hradilová, Chovancová and Vincent 2012, INVITE 2006–2008). Students are exposed to their first hands on experience with the technology, they get accustomed to seeing their image on the large screen, discuss sound issues as well as appearance and behaviour when on the camera (in order to get used to it, students e.g. prepare a short video message for their future peers). Presentation via VC equipment is another issue that needs practice, as technology new to most of the students is involved.

One of the issues that arose from the small scale research is the length of the pre-prepared speeches. The videoconferencing environment seems to put more pressure on the listener than a natural face-to-face situation, and it is important that the presentations are short (5 to 7 minutes) and include an interactive part to involve the audience. VC audience seems to be less tolerant towards longish presentations as they lack immediate physical presence of the speaker and often view only visual aids, thus lacking speaker’s eye-contact. To illustrate this point, an authentic video of an attentive audience during the first minutes of the presentation, followed by a video of the same but bored audience after seven minutes of the presentation are used as material to stimulate a discussion on how to prepare a presentation delivered via a videoconference (Maxim of Quantity, situation 10 is being applied here).

The five VC sessions have been designed to start from the easiest one and grade up to the most complex session. During the first VC, the students are supposed to gain confidence, to get to know each other and to practice the principles of videoconferencing discussed in the preparatory phase. The first session, therefore, consists of a questions and answers part where students find out about their peers, their studies and their student life, and a presentation proposals part, where students negotiate topics for their mini-presentations with their foreign counterparts. The aim is to find out what other students would be interested to hear and what they already know about the topics. The main areas of the presentations must be, however, connected with the topics of the more complex tasks students perform later on in the course. Traditionally, these were topics connected with legal issues, e.g. the law of tort, criminal law etc.

Results of the present analysis, however, uncovered a broad area worthy of students’ notice, namely principles of negotiation, Politeness Principles and formality in a court room. These are issues where general principles can be easily searched for and found. This is why short student presentations on these topics newly take place during the second session. They are followed by discussions chaired by the teacher and their purpose is to raise students’ awareness of the Quantity, Tact and Sympathy Maxims (situations in examples no 1 and 7 are used here to illustrate the point).

The third session is the first really challenging one as the students negotiate civil law cases. In groups, they are asked to study a case at home and prepare arguments and strategy for negotiation for the role assigned to them. Here, they need to demonstrate their knowledge of the case, the relevant law as well as observe principles of politeness and negotiation, i.e. principles newly introduced in the previous session. Three cases are usually discussed during a session by three different teams while the students who are not directly involved in current discussions make notes on student polite behaviour and strategies they apply while negotiating. Each of the case discussions is followed by a peer feedback on how students handled the situation and observed Politeness Principles.

The fourth session is devoted to public speeches and argumentation in structured and teacher-chaired academic debates. Students are assigned roles and opinions on a given controversial issue which they prepare at home in order to deliver a persuasive speech followed by a structured argument with their opponents. This serves as a reinforcement of the aforementioned new applications.

The last session is devoted to the performance of a mock trial. Students are assigned roles and given a transcript of the mock trial role-play. They prepare both individually and in small teams. They negotiate details with their foreign counterparts (using Wiki space) in order to prepare for the performance. The roleplay is chaired by a student who plays the role of a judge. Teachers merely monitor the session, facilitating anything the students or the communicative situation require.

Preparation for this session involves, among other issues, new exercises connected with the results of the corpus analysis, namely situations no. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 8. Situations 2, 3 and 8 are used as some of the examples in an exercise on politeness: e.g. read the following utterances and discuss why the hearer might be offended. Situations 4, 5 and 6 are used as authentic video clips for students to identify the problem in a communicative situation. Situation no. 9, on the other hand, is used as an example of good practice, where an obstacle in communication, caused by two different interpretations of the same word, is solved through patient negotiation of the meaning of the word in question.

The analysis of the corpus of recordings has identified some soft skills and pragmatic issues that need to be introduced to the students in order to raise their awareness of potentially threatening communicative situations or dysfunctional communication strategies and in order to practice what they, with the help of teaching material, identify as functional strategies in the context of particular communicative situations. These are especially in the areas of politeness, negotiating strategies and observance of the Cooperative Principle. Findings of this small scale research have been applied to teaching via videoconferencing methodology and their various aspects included into the course syllabus and materials.

These include namely activities aimed at the length of pre-prepared speeches supported by authentic video clips; focus of student presentation topics especially on issues related to negotiations and politeness, supported by exercises that lead to active peer observations of strategies fellow students use in discussions; notice-good-practice/bad-practice-exercises based on corpus material.

Further analysis of future videoed material is desirable in order to enrich the exercises developed for the course with more authentic examples.

Anastasiades, P. S. (2010) Interactive videoconferencing (IVC) as a crucial factor in K-12 education: towards a constructivism IVC pedagogy model under a cross-curricular thematic approach. in Rayler, A. C. ed. Videoconferencing: Technology, Impact and Application. New York: Nova Science Publishers, pp. 133-177

Borkin, A. & Reinhart, S. M. (1978) Excuse me and I am sorry. TESOL Quarterly, 12(1): pp. 57-70.

Brown, P. & Levinson, S. C. (1987) Politeness: some universals in language usage. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Budíková, B., Hradilová, A., Katrňáková, H. & Štěpánek, L. (2008) When Virtual Becomes Real: The Use of Videoconferencing in Language Teaching. Conference presentation. Nové směry ve výuce odborného jazyka, Olomouc, Czech Republic, 20 May 2008. Available online at http://invite.cjv.muni.cz/results.html

Denksteinová, M. & Podlásková, I. (2013) Videoconferencing and shared virtual learning of English for Specific Purposes. In Conference Proceedings of the 6th edition of ICT for Language Learning. Florence: Libreriauniversitaria.it.

Doughty, S. (2012) Why a Poles’ politeness can be lost in translation. Daily Mail, 14 February 2012.

Fraser, B. (1990) Perspectives on politeness. Journal of Pragmatics, 14: pp. 219-236.

Grice, P. (1991) Studies in the Way of Words. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, London, England.

Hopper, S. B. (2014) Bringing the world to the classroom through videoconferencing and project-based learning. In TechTrends, 58 (3), pp. 78- 88.

Hradilová, A., Chovancová, B. & Vincent, K. (2012) Videoconferencing for Students of Law. Brno: Masarykova univerzita.

Hradilová, A., Katrňáková, H. & Štěpánek, L. (2008) Response to a Call in Language Teaching. Conference presentation. CERCLES Conference. Sevilla, Spain,. Available online at http://invite.cjv.muni.cz/results.html.

Hradilová, A. & Štěpánek, L. (2007) Implementation of video conferencing within a frame of innovative learning infrastructures. Conference presentation. Diverse, Lillehammer. Available online at http://invite.cjv.muni.cz/results.html

INVITE (2006-2008) An Innovative Learning Infrastructure. Funded by the Leonardo da Vinci Programme (EU). Available online at http://invite.cjv.muni.cz/index.html.

Leech, G. N. (1983) Principles of Pragmatics. Longman, Harlow.

Morgan, J. (2008) Effective Communication in Video Conferencing. Invite Methodology Handbook. Available online at http://invite.cjv.muni.cz/material/method/meth_en.pdf

Morgan, J., Katrňáková, H., Hradilová, A. & Štěpánek, L.(2007) Developing a training programme for video conferencing for Project Invite. Conference presentation. Diverse,

Lillehammer, Norway. Available online at http://invite.cjv.muni.cz/results.html.

Suszczyńska, M. (1999) Apologizing in English, polish and Hungarian: Different languages, different strategies. Journal of Pragmatics, 31: pp. 1053-1065.

Štěpánek, L. & Hradilová, A. (2008) Implementing Videoconferencing Project: Results into Life-long Education. Conference presentation. Diverse, Haarlem, The Netherlands. Available online at http://invite.cjv.muni.cz/results.html.

Wierzbicka, A. (1985) Different cultures, different languages, different speech acts. Journal of Pragmatics, 9: pp. 145-178.

Wierzbicka, A. (1991) Cross-cultural pragmatics: The semantics of human interaction. Berlin, Mouton de Gruyter.

Transcript of Ex.: an abandoned house – Situation 9 “negotiating meaning of words”. The transcript is presented in its original form, i.e. it has not been edited.

Defendant: As I said before, our intention was to steel anything that could have some value for us.

Judge: Ad did you expect to find anything of value in the house?

Defendant: Yeah.

Judge: You have just brought up that you thought the house was abandoned.

Defendant: No, we didn’t think the house was abandoned, we just thought there was no one living there, we thought there was some stuff that we could sell.

Judge: So, in fact, you did suspect that someone lived there.

Defendant: No.

Judge: So, just to make sure, you didn’t think that the house was abandoned but you didn’t think someone lived there.

Defendant: Yes.

Judge: So what did you believe?

Defendant: We believed that the house is only for some farmers to stay there during the day when working on the field and during the night they go home and there isn’t anyone in the house.

Judge: What kind of valuables did you expect would be kept in the house if nobody lived there but only remained there during the daytime?

Defendant: Well. We thought there might be some tools that the farmers use when working on the field, just anything, anything that could be of any value.

Please check the Practical Uses of Technology in the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the English Language Improvement for Adults course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

|