Presentation Abstracts as a Tool for Student Motivation in ESP Classes

Barbora Chovancová and Štěpánka Bilová, Czech Republic

Barbora Chovancová and Štěpánka Bilová are teachers of Legal English at Masaryk University Language Centre, Brno, Czech Republic. They have extensive experience in designing ESP teaching materials. They share the belief that teaching materials need to be both maximally effective and enjoyable for both students and teachers.

Menu

Abstract

Key words

Presentations – relevant issues

Background

A few magic touches that work

Presentation abstracts

Advantages and disadvantages

Feedback from students

Conclusions

References

The essay describes how two teaching ideas, namely that of creating tasks for the audience and writing presentation abstracts, can be employed to make students more actively involved in presentation planning, delivery and reception. The methodology is described in detail, with student feedback added to allow readers to make their own conclusions on how well it works and how it is perceived by Legal English undergraduates.

Legal English, English for Specific Purposes (ESP), presentation skills, motivation, student involvement

Out of the extensive theoretical list of studies on presentation skills training, references to three aspects of issues relevant to the present article have been chosen, namely the teacher as a role model, the motivational aspect of (self-) and peer assessment, and classroom practice methodology.

Teachers serve as role models for the students, the presentation style of teacher should therefore be of a very high quality. Research on methodology of teaching effectively at universities is available (cf. Newble and Cannon, 2000), teachers can thus access sufficient support material for their professional development.

Self and peer assessment, current issues dealt with by the researchers in the field of teaching presentation skills, are addressed (for example) by Lynch and Maclean (2003) or more recently by De Grez, Valcke and Roozen (2012). The latter study shows that “students’ perceptions of peer assessments will influence their willingness to take into account the feedback generated by peer assessment and to actually do something with that feedback” (De Grez et al. 2012: 138).

Finally, this article aims to be relevant for teaching practice. Therefore, it is correct to say here that as far as practical methodology of student presentations is concerned, there is a wide choice of materials that help instructors to prepare their students for public speaking. To give an example, easy to follow instructions aimed at academic presentation for non-native speakers can be found at https://www.llas.ac.uk/video/6097. A very hands-on, practical and creative example of material to be used by teachers can be found at http://speakingoutevents.com/education/staff/.

Presentation skills became a part of the Legal English syllabus at the Faculty of Law, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic over 10 years ago. The positive aspects have been evident from the very beginning. Not only do presentations give students a chance to practise their speaking skills, the students also acquire soft skills valuable for their future careers. What is more, the students appreciate it. Good presentation skills featured on top of the list of skills a Law graduate should have in a “transferred” needs analysis carried out with former students of the above mentioned institution (Chovancová, 2013 and 2014).

From the teacher’s perspective, presentations are beneficial for those who stand in front of the class and speak; the problem that needs to be addressed, however, is how to increase audience involvement. Engaging students in tasks is a never-ending challenge in the teaching profession, some tips related to speaking activities can be found in Bilová (2014a,b).

In the light of the above mentioned, students’ are required to give a team presentation in groups of three. As members of their presentation groups, they are asked to choose a legal topic, divide their roles and thus gain additional useful experience of team work.

The class size of about twenty means that students spend considerably more time listening to others presenting than giving presentation themselves. To keep them focused on the presentation and use the time effectively, the following tasks have been developed in order to increase the motivation and active participation of presentation audiences.

1. Task for the audience

The initial methodology improvement, designed to address the problem of student involvement, is the introduction of a ‘task for the audience’. This has a dual role. The first aim is to make the presenters think of their audience globally (i.e. what the most important message is). The second aim is to make the non-presenting students pay attention in order to be able to perform the task.

The tasks vary according to suitability for a particular topic and creativity of a particular presentation group. They range from simple cross-word puzzles and gap fills to more complex activities such as a simplified simulation of presidential elections.

Apart from the natural increase of motivation by being actively involved in an activity, the audience members are further motivated in other ways. For instance, the presenters sometimes bring sweets and other small prizes to reward the audience for a fast completion of the given task and to ensure audience cooperation. Thanks to the careful preparation of the presenting group, it is only the most un-competitive members of the audience who, instead of following the presentation, opt for surfing the Internet or daydreaming.

2. Writing presentation abstracts

Another addition to student presentation training is the introduction of ‘presentation abstracts’. These are provided to the audience in a written form at the beginning of the term. The reasons for this innovation were twofold: it has been felt on the level of the Faculty of Law that the students are not sufficiently equipped with academic writing skills (an abstract in English is a required part of their diploma thesis). Also, the teachers of Legal English have been looking for ways of making the presentation teaching even more effective. The inclusion of presentation abstracts in the course design has made the students better aware of their audience. At the same time, the abstracts help the audience to focus on what the presenters have prepared.

Apart from that, abstracts also make the learning situation more realistic/life-like and topical, thus making the students rise to an exciting challenge. As noted by Pulko and Parikh, “A successful training session must begin by creating a sense of urgency and somehow capturing the interest of the audience, usually by emphasising the importance of the topic and its relevance” (Pulko and Parikh 2003: 244).

Preparation stage

First, students are taught rules for writing abstracts according to the requirements for their theses. However, for the purpose of their presentations in Legal English classes, they are given more leeway to make their abstracts more creative and eye-catching. It is stressed to them that they need to keep in mind who their audiences is and what expectations they have.

The practice of teaching presentation abstracts has shown that teachers can employ two different strategies. The first may be called the ‘poster-on-the-wall strategy’, the second the ‘posting-on-the-web strategy’.

Poster-on-the-wall strategy

Students are asked to send their abstracts to the teacher who prints them on A4 sheets of paper and brings them to the classroom. Abstracts are stuck to the wall and students are asked to wander around the classroom, read the abstracts and write any comment they have about each of the proposed presentations (apart from their own). They write the comments directly on the paper with the abstract of each presentation. After reading all the abstracts and writing comments on each of the sheets, students are allowed sit down and start working on another assignment. Finally, the teacher collects the abstracts, corrects the major mistakes and writes his/her feedback on the content of the presentation. The sheets are then returned to the authors.

Posting-on-the-web strategy

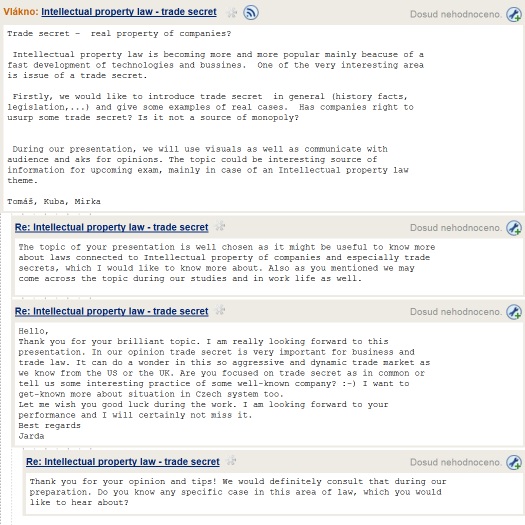

The second strategy involves the use of ICT. The students are asked to post their own abstracts in the Information System of Masaryk University, which is the university platform providing electronic support for managing study-related data and offering a wide range of administrative, e-learning, and communication tools. Once the abstracts are made available, the fellow students are invited to read their classmates’ abstracts and comment on them – mainly from the point of view of content. The authors of the abstracts can answer questions and address any comments suggested by the readers (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: A sample of an abstract posted by one group and related comments in the discussion forum, March 2015

Both strategies have advantages and disadvantages. These concern mainly the amount of time needed to complete the tasks and the degree of teacher involvement.

Poster-on-the-wall strategy

An important advantage of this strategy is that all the students are involved. They all actively read all of the abstracts and write comments on the abstracts posted on the walls. Even more important, students get feedback from their teachers. This includes not only factual comments on the proposed presentation but also practical hints about the writing of abstracts. However, the main disadvantage of this activity is that it is quite time-consuming.

Posting-on-the-web strategy

The chief benefit of this method is that once the teacher sets up the task, all the rest is done by the students themselves. It is the students who post the abstracts and comment on each other’s abstracts. Also, they do so in their own time. One of the disadvantages is that not all the students actually give the comments because they are expected to do so in their own time and on a voluntary basis. In some groups the virtual discussion goes really well, with comments and replies going back and forth. In others, however, only a few students get involved. Equally important, as the teacher does not get directly involved and only monitors the discussion, students do not get feedback from the teacher; thus miss the chance of improvement in the future. Naturally, the teacher can easily enter the discussion to provide feedback on the web page. In our case, however, the teachers tend to give general feedback in the following lesson and offer individual tutorials if the students feel they need it. In some cases the involvement of teacher is necessary – especially when there are two presentation abstracts on the same or very similar topics, or if a topic is too broad and the teacher suggests narrowing it down.

What the students think – poster-on-the-wall

First of all, writing the abstracts and having their classmates comment on them make the students aware of the fact that the presentation is made not only for the teacher (and the credit) but that it will be watched and judged by a real audience, that of their peers.

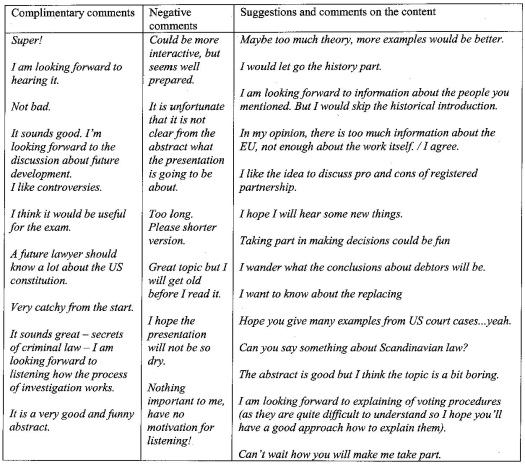

Students are asked not only to comment on the abstracts, but also make suggestions and comments that the presenters can take into account when preparing the presentation outlined in the abstract. As Table 1 shows, the comments that students offered in our classes have varied greatly:

Table 1: Students’ comments handwritten on the posters with abstracts (unedited versions)

The students are not allowed to use the word “interesting” in their comments (not only because of its double meaning but also to encourage them to actively think about the abstracts and appropriate adjectives). Great majority of comments were positive and encouraging, but as you can see, some of the negative comments are quite scathing. Although nearly all the students commented on the content of the abstracts, a few also noticed the form, e.g. “…an abstract should look like yours”.

Comments in the internet discussion of the abstracts

The task for the students is more specific. They are asked to write down comments on at least three abstracts of their classmates’ presentations. They are also asked to explain why they were looking forward to the chosen presentation. While comments on the posters tend to be shorter and simpler (because of the mode of their creation, i.e. student thinking on their feet a jotting their ideas on the wall), in the virtual environment the students have less time and space constraints and the results show higher level of cohesion, sophistication and intertextuality (see Figure 1 and Table 2). It is also interesting to note that only one negative comment could be found – possibly because of a partial lack of anonymity in this mode of feedback. Sample responses can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2: Samples of electronically submitted fellow students’ comments written on-line (unedited versions)

At the end of the term, the students were given questionnaires in order to find out what they thought of the inclusion of abstracts into the presentation syllabus.

The paper-on-the-wall students were given paper questionnaires and filled them in their last lesson. The feedback received from 39 questionnaires filled by the students and out of this number, only 2 were negative (describing abstracts as “not useful” and “something we had to do”). All the others were overwhelmingly positive. Students saw them beneficial in the following areas: it helped them to organize their thoughts (Abstracts are a good thing because they make people think about the presentation earlier, it helps to put the thoughts together.), they said they tried harder because they wanted to make a good impression on their colleagues (In the class it [the abstract] make it look more important, so I think it brings better results.), it helped them to improve their presentations (We changed our presentation a bit after reading comments from our classmates and the teacher), reassured the presenters in cases of positive reaction (People could comment on our ideas and we were happy because there were good comments.), but the writing of the comments was a good practice in itself (When I was not interested in the topic, it was hard to say something positive – or simply not stupid.)

The posting-on-the-web students were given on-line questionnaires. Only 15 students out of 59 filled them in, doing so with minimal possible involvement – just ticking the boxes and not writing any comments. There were a few notable exceptions. One commented on presentations in general “I consider the presentation much more educative than normal studying. Every time you have to teach something, you have to know it. Excellent form to make student study really hard” Another focused on the work angle: “It was good, because there were 3 members in my group and the abstract helped us to summarize what the presentation would be about. Otherwise we would do that a week before presentation.”

There were no negative responses – everybody found at least one positive aspect on writing abstracts. The questionnaire included the following statements/questions (the numbers in the parentheses indicate the number of students who ticked this answer):

- I consider writing abstracts useful for my future studies/carrier. – Yes (8)/ Only a little (7)/ No (0)

- I had enough information on how to write abstracts. – Yes (14)/ No (0)

- Which format of writing abstracts did you use? On the web (11)/ On the wall (3)

- Did you like the format? Yes (12)/ A little (2)/ No (0)

- Did preparing the abstracts have any positive effects on the future presentations?

- Writing the abstract helped my group/me in shaping the presentation. (9)

- Writing the abstract made my group/me more aware of the audience. (2)

- The abstract made me prepare more. (3)

- The abstracts helped the audience - they were prepared for the topics. (5)

- Preparing the abstract was a good start for the team work on our presentation. (10)

- I can’t see any positive effects of writing abstracts. (0)

- When comparing the abstract and the presentation, the content of your presentation

- Was exactly as you stated in the abstract. (3)

- Followed the main idea of the abstract, but details were different. (11)

- Was different from what was suggested in the abstract. (0)

To conclude, audience involvement is crucial for the success of the presentation classes as it raises motivation of all students – those who present as well as those who listen. The essay shows two ideas how this goal can be achieved: tasks for the audience and presentation abstracts. Using abstracts accompanied by the feedback by fellow students in ESP presentation classes appears to have positive results. By preparing the abstract, the students have to concentrate on their presentation in advance. Moreover, when given feedback by their peers, they tend to try harder.

Writing of abstracts provides students with practice in academic writing skills which they will find useful in their future careers. Both strategies (comments on paper and online) proved to be useful and beneficial in different ways and can be recommended for being included in presentation classes in the future, but the trend generally is to include ICT technologies in the classroom so that the online version is likely to remain.

Bilová, Š. (2014a). Enhancing Students’ Speaking Skills. In: Nedoma, R.(ed.) Foreign Language Competence as an Integral Component of the University Graduate Profile IV. Brno: Univerzita Obrany, 38–43.

Bilová, Š. (2014b). Getting students more involved in the tasks. In: Pattison, T. (ed.) IATEFL 2014 Harrogate Conference Selections. Kent, UK, 164–165.

Chovancová, B. (2013). From classroom to courtroom: Preparing legal English students for the real world. In: Vystrčilová, R. (ed.) Právní jazyk – od teorie k praxi (Legal Language: From Theory to Practice). Olomouc: Palacký University.

Chovancová, B. (2014). Needs analysis and ESP course design: Self-perception of language needs among pre-service students. Studies in Logic, Grammar and Rhetoric 38 (1): Issues in Teaching and Translating English for Specific Purposes (ed. by H. Sierocka and H. Swieczkowska), 43–57.

De Grez, L., M. Valcke, and I. Roozen (2012). How effective are self- and peer assessment of oral presentation skills compared with teachers’ assessments? Active Learning in Higher Education 13(2): 129–142.

Lynch, T. and J. Maclean (2003). Effects of Feedback on Performance: A Study of Advanced Learners on an ESP Speaking Course. Working Papers in Applied Linguistics 12: 19–44.

Newble, D. and R. Cannon (2000). A Handbook for Teachers in Universities and Colleges: A Guide To Improving Teaching Methods. Oxon: Routledge.

Pulko, S. H. and S. Parikh (2003). Teaching ‘Soft’ Skills to Engineers. International Journal of Electrical Engineering Education, 243–254.

Please check the Creative Methodology for the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Practical Uses of Technology in the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

|