Latin as a Language for Specific Purposes: Its Development and Current Trends

Jozefa Artimová and Libor Švanda, Czech Republic

Jozefa Artimová is a teacher at Masaryk University Language Centre, Brno, Czech Republic. Her main professional interest include Latin medical terminology, its history, development and translation. She co-authored Slovak translation of Nomina anatomica veterinaria and Monolingual dictionary of Latin anatomical terms. She is also focusing on innovations in the area of Latin medical terminology didactics.

E-mail: pepartim@me.com

Libor Švanda is a teacher at Masaryk University Language Centre, Brno, Czech Republic. Besides teaching Latin Medical Terminology, he is interested in Medieval Latin. He participated on several editing projects (including critical editions of Iohannis Hus Opera Omnia, vol. 17 and 24). Current professional interests are Latin as a LSP (Language for Specific Purpose) in medical records and Latin theological treatises by John Hus.

E-mail: svanda@phil.muni.cz

Menu

Introduction

Background

How to adapt to current trends?

Conclusions

References

Latin as a typically non-spoken language is usually excluded from Common European Framework of Reference for Languages and even many professionals would not think about technical Latin (in medicine, law and natural sciences) as part of LSP (Language for Specific Purpose). Nevertheless, due to political changes in the system of several countries in the Central and Eastern Europe shortly after the World War II gave birth to the Latin as LSP and this paper will describe that process. The description is followed by the current trends in teaching Latin as LSP.

Before 1948 medical faculties in the former Czechoslovakia, or many other countries of the Central and Eastern Europe, did not offer courses of Latin medical terminology. Since many students used to be trained in classical Latin, or even in classical Greek, already during their secondary education, no need was felt for such courses at the tertiary level. Nevertheless, due to political changes and transformations in the system of secondary education, Latin ceased to be the obligatory subject and its command, taken for granted before 1948, gradually faded out. To the dismay of anatomy teachers and other medical professionals, in September 1956 the first students with zero knowledge of Latin entered medical faculties in Czechoslovakia, and the institutional decision to fill the gap in the formal education of students ensued their influx. Between late 1950’s and early 1960’s the majority of medical faculties introduced one-year, in more adverse cases one-semester of an obligatory Latin course for students of medicine.

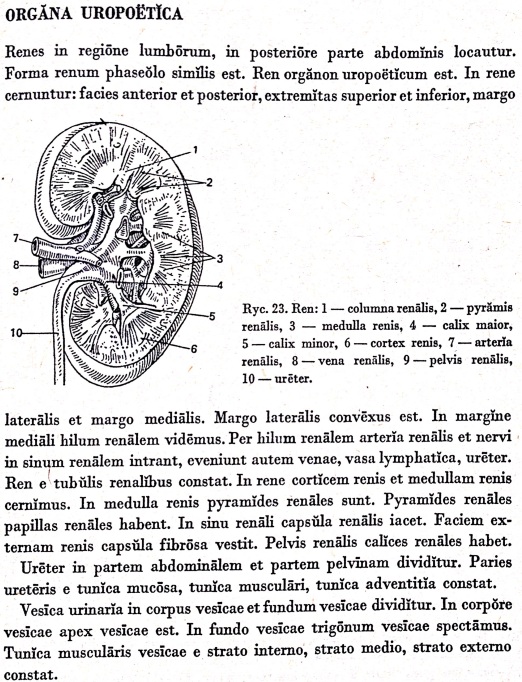

Since 1960’s teaching Latin as an LSP has gone through different stages, which can be easily observed while reviewing textbooks designed for these courses. First teaching materials for Latin used at medical faculties were aimed at representing the classical language in its complexity; therefore, the verbal system was a crucial part of the curricula. Despite extremely restricted time allotted to such language education (never more than 60 teaching hours) students were still believed to be able to master Latin as a language and a very good command and orientation in the grammatical structure of their mother tongue was implied. At the end of the course, students were expected to understand and translate Latin texts – either modern, written by authors of the textbooks on different medical topics (Fig. 1), or those of ancient medical writers. Above the content of classical Latin textbooks, the basics of pharmacological and chemical nomenclature together with the basics of classical Greek became an integral part of these course books.

Fig. 1. Text on uropoietic organs by S. Nowicka (1963)

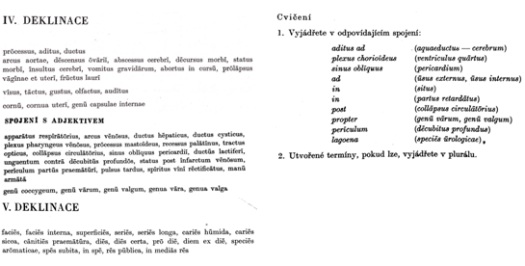

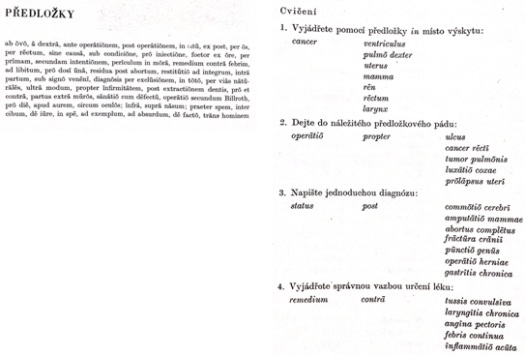

To the subject and its textbooks, originally named “Latin for students of medicine”, a new name “Latin medical terminology” was assigned around 1970’s. The change in the title of majority of available course books was not accidental, at least not in the Czechoslovak context, where it signalized a shift towards more pragmatically oriented curricula. The verbal system, together with other parts of speech, which rarely appear in authentic medical records, had been reduced to a minimum and the teaching focused on mastering the nominal system. Students were trained to understand and form precise and grammatically correct technical terms from the field of the anatomical, clinical, pharmaceutical and at least partly also chemical nomenclature. Courses aiming to cover the nomenclature as a whole had to introduce Latin and Greek nominal system including irregularities and exceptions. The exercises were devised not so much to drill grammar as to illustrate all possible grammatical features of Latin medical terminology that a physician could ever encounter during her or his medical practice; therefore, extensive vocabulary lists have been typically included in each lesson. Unfortunately, it was reflected neither in the variability nor in the number of exercises (Figs. 2 and 3) so the level of pragmatic knowledge and ability to produce correct medical records at the end of courses remained questionable.

The book by Kábrt and Chlumská set an example of a textbook for Latin as an LSP in the field of medical terminology. Later development of teaching materials for this subject was confined to updates of the nomenclature, especially anatomical, but the fundamental methodological and organisational setting, except for the moderate increase in the number of exercises, remained unaltered.

Figures show the translation exercises to practice the nouns of 4th and 5th declensions, the connection of those nouns with adjectives, one drilling exercises where these nouns are connected with prepositions and transformation exercise based on forming plural forms of those nouns. Fig. 2. shows translation exercises (pp. 49, 51, 53) and two drilling exercises (p. 54) from Lékařská terminologie by Kábrt, J. and Chlumská, E. (1972). Unit 4 introduces Latin nouns of 4th and 5th declension; translation exercises consist in blend of terms from anatomical, clinical and pharmaceutical nomenclature accompanied by a few set phrases; vocabulary of the unit contains 76 lexical items.

Fig. 3. Unit 14 of Lékařská terminologie by Kábrt, J. and Chlumská, E. (1972). The unit focuses on Latin prepositions; it includes one translation exercise with wide variety of prepositional phrases (some of them not directly related to the field of medical terminology) and four drilling exercises on forming the clinical expressions (pp. 114 and 116). The exercises are based on connecting nouns with a variety of prepositions in phrases which could be used as (a) authentic diagnostic records.

Towards the beginning of the new millennia, medical faculties introduced specialised full-time study bachelor courses and a specific type of distance study combined with face-to-face tutorial courses (e.g. General Nurse, Nurse-Midwife, Physiotherapy, Nutritional Therapist and Radiology Assistant). Within such bachelor study programmes, the courses of Latin medical terminology were reduced (to not more than 30 teaching hours) and common textbooks originally designed for students of General Medicine became difficult to adapt. To adjust to the modified needs, Latin lecturers had to simplify the textbooks in terms of the thematic content and reduction of vocabulary.

From 2009 to 2012, within the COMPACT project (CZ.1.07/2.2.00/07.0442), the team of Latin medical terminology teachers at the Medical Faculty of Masaryk University gained a better insight into the needs of registered nurses and allied health personnel and became interested in the pragmatic use of Latin during the carrier of these professions. Pořízková (2015) managed to collect the corpus of authentic medical records with more than 100 thousand individual records from two university hospitals in Brno and one in Prague during the project IMPACT (CZ.1.07/ 2.2.00/28.0233) between 2012 and 2015. In the course of the IMPACT project the team decided to take advantage of the compiled authentic material and to tailor the courses to the needs of particular bachelor fields of study.

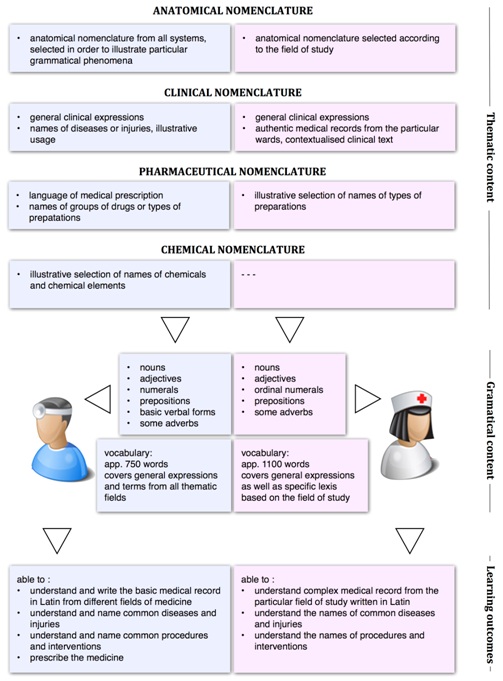

Instead of introducing students to the overwhelming area of Latin medical terminology as a whole, the main focus of teaching has shifted. Students are expected to master the nomenclature of the anatomical system that is essential to their particular field of study in detail. Clinical terminology is not presented as a list of unrelated clinical terms anymore; the emphasis is rather given on the profound understanding of authentic medical records, which are representative for the given field of medicine. The difference in the study content and expected learning outcomes between traditional and modified course books is summarized in the chart (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. The comparison of traditional (blue) and modified (pink) course books

Teaching materials of Latin medical terminology prepared by our department focus on the way the essential grammatical material is presented. On top of common translation exercises, a complex approach was opted for, as it is not expected that bachelor programmes students will have a deep knowledge of anatomy and clinics. For the first time the approaches typical for textbooks written for learning the living languages were utilized together with inventive graphical representation of the grammatical material and original illustrations. The number of exercises has increased and variability of exercises has also significantly changed. The classical translation exercise is still an inseparable part of the Latin textbook, but has been supplemented with exercises of different formats: multiple-choice, multiple-response, matching, true/false, crossword puzzle, fill-in-the-blank, structure identification and labelling.

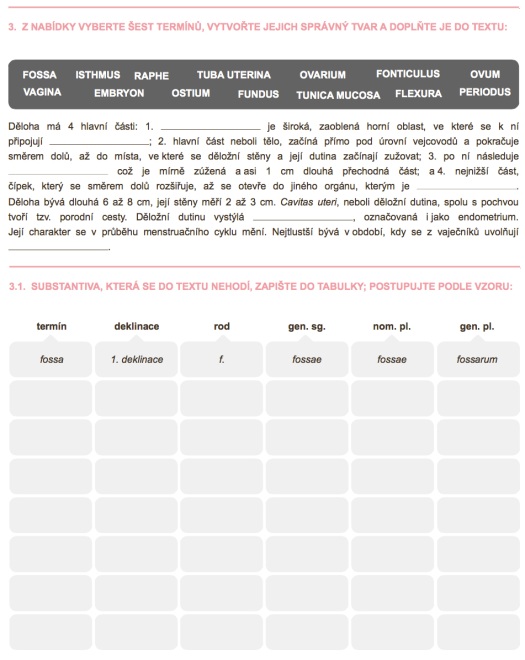

Masaryk University Language Centre’s Latin teaching materials remain bilingual; the language of grammar and exercise instruction is Czech, the content of exercises remains Latin, except for those cases where texts or discrete definitions are employed. Shorter texts or discrete definitions written in Czech have never been used in this type of textbooks before. They are used either in order to supply the background information for multiple-choice exercises (Fig. 5) or to provide the context for various types of drilling and vocabulary development exercises in order to contextualize the use of a particular term.

Fig. 5. Shows exercises 3 and 3.1 from Unit 2 of Terminologia Graeco-Latina medica pro studijní obor porodní asistentka by Artimová, J. et al. (2015). The unit aims at Latin nouns of 2nd declension. The short text is accompanied by a multiple-choice exercise, which is followed by a vocabulary drilling exercise (pp. 16-17). The instruction for the exercise 3 reads as: “Choose six terms that fit into the text and use them in the correct form”. The instruction for the exercise 3.1. says: “Nouns that did not fit to the text use to practice the grammatical forms, follow the example”.

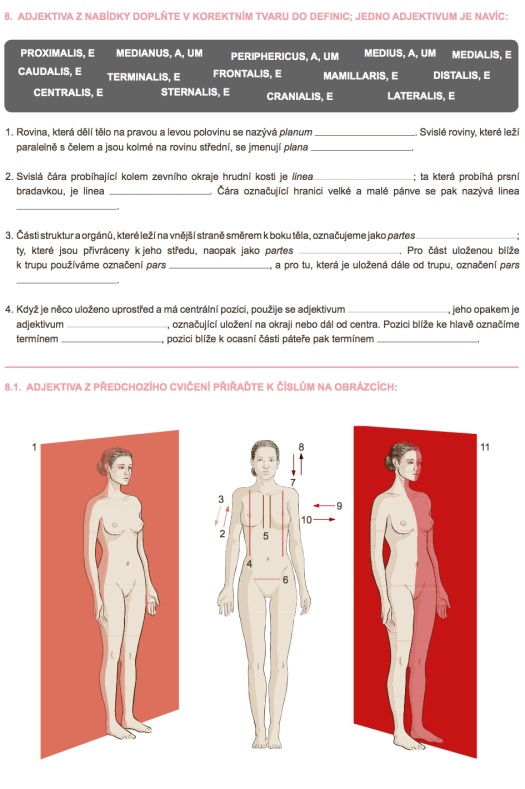

In the majority of cases the illustrations from the field of anatomy are used with the intent to visualize anatomical terms, to interconnect the grammatical content with its anatomical part (Fig. 6) and to support the retention of the acquired knowledge. Returning illustrations to Latin textbooks is regarded as one of the crucial turning points within the adaptation process of teaching Latin as an LSP to present trends.

Fig. 6. Shows exercises 8 and 8.1 from Unit 4 of Terminologia Graeco-Latina medica pro studijní obor porodní asistentka by Artimová, J. et al. (2015). The definitions are used to introduce and contextualise the usage of derived adjectives referring to the position and direction of body parts; the labelling exercise 8.1 verifies the proper use and understanding (pp. 38-39). The instruction for the exercise 8 (reads) as: “Fit the given adjectives into the appropriate definitions, one of the adjectives will not be used”. The instruction for the exercise 8.1. says: “Connect the adjectives from the previous exercise to the number in the images”.

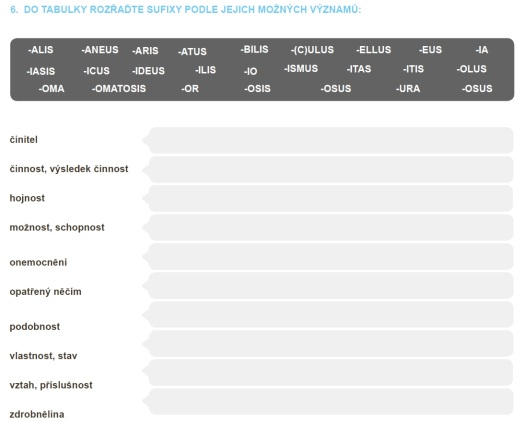

Special attention is also paid to the gradual development of students’ vocabulary. Recognition and pragmatic use of paradigmatic semantic relations among words, especially synonymy, antonym and collocations, together with the basic principles of derivation and word-formation are not taught at the end of the course as in traditional textbooks, but became an integral part of the study material from the first unit on (Figs. 6 and 7).

Fig. 7 represents the exercise 6 from Unit 9 of Terminologia Graeco-Latina medica pro studijní obory fyzioterapie a všeobecná sestra by Švanda, L. et al. (2015). The list of derivational endings is transformed into a matching exercise (p. 82). The instruction for the exercise 6 says: “Sort the suffixes from the box to the table according to their meaning.”

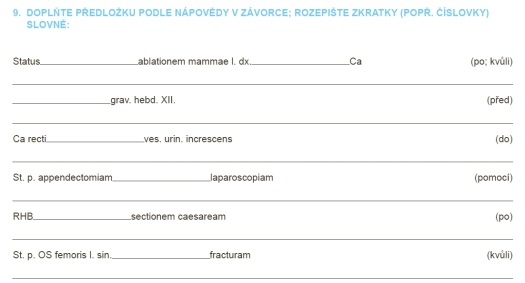

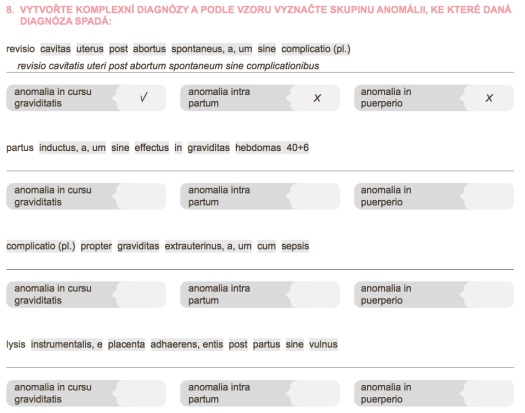

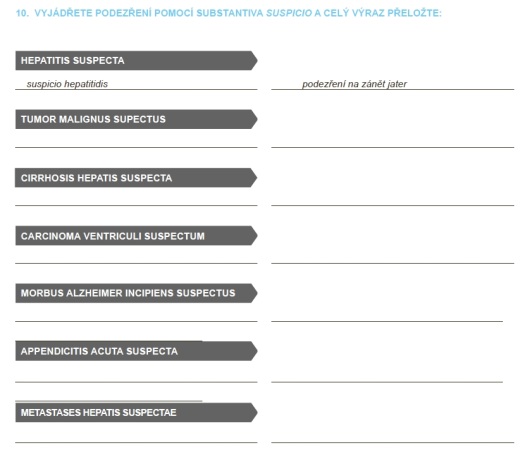

The most important innovation of the new teaching material lies in the use of authentic medical reports and documentation. The collected corpus of individual records served as a source for the excerption of suitable material for the textbook itself; nevertheless, the way in which particular cases are recorded allows students to observe how the technical medical Latin is used in real life situations and to get acquainted with its peculiarities. The use of authentic medical documentation in class is often challenging for the teacher, who is typically not a medical professional but a linguist. In order to analyze the collected records in detail, to understand it and to be able to teach it to the students, the cooperation of physician was necessary. (A thorough understanding of the complex nature of a medical record, its high variability and the way the content is abbreviated has an important part of the competence of the allied health personnel and none of the previously published textbooks take this into consideration (Figs. 8 and 10).

Fig. 8. Shows exercise 9 from Unit 9 of Terminologia Graeco-Latina medica pro studijní obory fyzioterapie a všeobecná sestra by Švanda, L. et al. (2015). The authentic records are presented in order to drill prepositional phrases (p. 63). The instruction for the exercise 9 says: “Choose the correct preposition based on hints in the brackets, give full forms of the abbreviated words or numerals”.

Fig. 9. Shows exercise 8 from Unit 8 of Terminologia Graeco-Latina medica pro studijní obor porodní asistentka by Artimová, J. et al. (2015). The authentic records are formed and matched with a type of anomaly (p. 82). The instruction for the exercise 8 says as: “From complex diagnoses and based on the example mark the group of anomalies into which the given diagnose belongs to”.

Fig. 10 Shows exercise 10 from Unit 8 of Terminologia Graeco-Latina medica pro studijní obory fyzioterapie a všeobecná sestra by Švanda, L. et al. (2015). The transformation exercise is used to form and understand (physicist’s) expression of certainty or uncertainty of the given diagnosis (p. 74). The instruction for the exercise 10 says: “Transform the given expressions using the noun suspicion and translate the phrases.”

It has become standard at Masaryk University to accompany new study materials by e-learning support materials, at least in the form of interactive syllabi, which provides a basic interaction between the teachers and their students outside the class. For a distance study combined with face-to-face tutorial courses the e-learning support has turned out to be a must. The control over the (continuous) progress of students and instant feedback offered by the electronic version of the study materials not only to students, but also to teachers, has proved to be highly efficient. The route learning part of the course is carried out outside the class. During the face-to-face tutorials the teacher can focus on explaining grammar and solving particular problems.

The modified study materials have been piloted during the academic years (2013/2014 and 2014/2015.) To measure the students’ satisfaction with the methodology and content of the teaching materials an online-questionnaire was used. (63%) of the students highly appreciated the thematic content of the material and considered it to be fully compatible with their field of study. The knowledge acquired during the Latin medical terminology course had the highest impact for further study of anatomy and physiology. The use of authentic medical records was considered to be highly motivational. Moreover, clear arrangement and graphical representation of the grammatical content added to its attractiveness.

Artimová, J., Pořízková, K., Švanda, L., & Dávidová, E. (2015, in press). Terminologia Graeco-Latina medica pro studijní obor porodní asistentka. [Terminologia Graeco-Latina Medica for Nurses-Midwifes.] Brno: Masarykova univerzita

Beran, A. (2013). Výuka řecko-latinské lékařské terminologie ve studijních programech všeobecného lékařství na lékařských fakultách v České republice a ve světě. [Greek and Latin Medical Terminology Instruction in Programmes of General Medicine at Medical Schools in the Czech Republic and abroad.] Dissertation thesis. Praha: Univerzita Karlova

Kábrt, J., & Chlumská, E. (1972). Lékařská terminologie. [Medical Terminology.] Praha: Avicenum

Nowicka, S. (1963). Język łaciński : skrypt dla studentów medycyny. [Latin Language: University Textbook for Students of Medicine.] Łódź: Academia Medyczna

Pořízková, K., & Blahuš, M. (2015). Korpus autentických klinických diagnóz v prostředí softwaru Sketch Engine. [Corpus of Authentic Clinical Diagnoses: Sketch Engine as a Tool for Innovative Approach to Teaching Latin Medical Terminology.] In: Kateřina Pořízková and Libor Švanda. Latinitas Medica. [online]. Brno: Masarykova univerzita, pp. 31-42. Available from: .

Švanda, L., & Artimová, J. (2015). Diverzifikace inovovaných výukových materiálů lékařské latiny dle oborového zaměření. [Diversification of Innovated Teaching Materials for Medical Latin with Regard to Various Specialisations.] In: Kateřina Pořízková and Libor Švanda. Latinitas medica. [online]. Brno: Masarykova univerzita, pp. 119-121. Available from: .

Švanda, L., Pořízková, K., Artimová, J., & Dávidová, E. (2015, in press). Terminologia Graeco-Latina medica pro studijní obory fyzioterapie a všeobecná sestra [Terminologia Graeco-Latina Medica for Physiotherapists and General Nurses.] Brno: Masarykova univerzita

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

|