Editorial

The article originally was published in The Teacher magazine www.teacher.pl

Visiting Exciting Toruń – an Interdisciplinary Project for High School Students

Aleksandra Zaparucha, Poland

Aleksandra Zaparucha is an independent EFL/CLIL trainer, consultant and author from Toruń, Poland. E-mail: ola.zaparucha@gmail.com

Menu

Abstract

Introduction

Interdisciplinary (cross-curricular) teaching

Teaching through projects

Interdisciplinary school project

Examples of the project tasks

Summary

References

The paper presents the rationale for carrying out both interdisciplinary (cross-curricular) teaching, teaching through projects and integrating core subjects with language acquisition. The project was prepared for a group of Polish and English students taking part in a youth exchange. It was designed to serve as a sightseeing tour around the historical centre of Toruń. The activity combined Geography, History, History of Art and art. As the activity was done in English, for the Polish students it also served as a hard CLIL project.

None of the core subjects taught at modern schools can stand alone, including foreign languages, which are indispensable in multicultural and multilingual Europe. As a result, school curricula should put stress on careful selection of what knowledge and skills to teach and at what age. To do so, curricular boundaries of core subjects should be redefined in order to change their contents, crossed through co-operation between various subject departments, or even broken if teaching other subjects is done mainly or entirely in a foreign language (Doyle, 2000).

Another important issue is to make students themselves aware of the fact that the knowledge from different subjects can and should be used for other classes as knowledge has no limits or borders. To do so it is necessary to undertake numerous activities to help students understand the interdisciplinary character of real life challenges.

Interdisciplinary teaching, also known as cross-curricular teaching, is understood as a conscious process of applying knowledge from more than one core school subjects at a time. The selected disciplines are often related through a central topic, or a theme or unit, such as ‘water’ or ‘food’. Such a structure, besides integrating content areas, enables teachers to engage students in learning activities which are both meaningful and functional (Tompkins & Hoskisson, 1991, in: Pikulski and Cooper, undated).

By employing interdisciplinary teaching it is possible to tackle some of the issues modern education faces, such as fragmentation of knowledge and teaching isolated skills. This mode of teaching is a medium to transfer knowledge, teach thinking and reasoning skills, and use a curriculum which is more relevant to students (Marzano, 1991; Perkins, 1991, in: Pikulski and Cooper, undated).

According to J. Pikulski and J. Cooper (undated), other benefits of interdisciplinary instruction include the fact that it shows students its new applications and integrity. As a result, the learning process is improved.

In terms of foreign languages, K. Brown and M. Brown (1996) state that by introducing them into interdisciplinary activities, the entire process of foreign language acquisition gets enhanced. Moreover, foreign languages increase the level of students’ motivation, encourage collaboration in both teaching and planning processes, as well as generally support a national curriculum by highlighting a broader dimension of education and its goals. Besides, ‘by building on learning in other curriculum areas and on pupils' understanding of issues and events in the wider world outside the classroom, we offer pupils a relevant and coherent experience in their language lessons and in all their subjects.’ (Brown and Brown, 1996, p. 41).

School projects have an established position among teachers of both foreign languages and non-language subjects. For instance, all contemporary English coursebooks for school students include a number of topics to be presented in a form of a project. This can be a poster on a holiday destination, a famous pop star or a family tree, which, besides giving a practice in writing, increase the students’ motivation and engagement by presonalising the topic. Other projects may integrate all the language skills (integrated-skills approach in teaching English as a Foreign/Second Language (EFL/ESL), such as ‘Street interview on a specific topic’ or ‘String and pin display: tourist destinations within a town’ (Fried-Booth, 1997).

For teachers of non-language subjects the project method is a great way to exchange the textbook as the main source of information for something new, especially if the project is well prepared, both methodologically and practically. In terms of their duration, projects may range from short one-subject projects to a few-days events integrating more than one discipline (Bailey, 1991; Gołębniak, 2002; Zaparucha 2006, 2007b, 2008). No matter what the organisation aspect of a project work is, it enables the students to ‘put their hands on’ a given topic, be it History, Geography or Art.

Taking all the above into consideration, projects for integrating different school subjects, including a foreign language, are a good solution. Moreover, project work, as a part of Content and Language Integrated Learning, or CLIL, advocated by the EU (see: http://www.factworld.info/materials.htm), allows the learners to observe that a foreign language is a necessary tool for solving real problems and undertaking real tasks. Thus, the motivation, independence and confidence of learners grow. Besides, the project method for both, language and content-teaching, gives the very teacher a chance to observe the students in various learning situations and thus to evaluate their abilities, skills and needs (Zaparucha, 2007a).

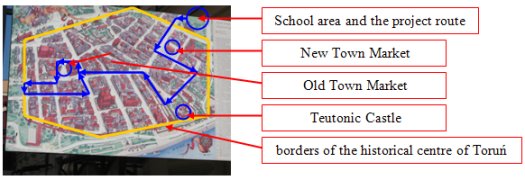

The following interdisciplinary project was designed for a school youth exchange between the Secondary School number 10 in Toruń, Poland, and the European School in Culham, the UK, which included a few students of French origin. It served as a sightseeing tour around the historical Old Town of Toruń (Fig. 1 and 2). A carefully designed activity combined Geography, History, History of Art and Art. As the activity was done in English, for the Polish students it also served as a ‘hard’ CLIL project (Kelly, undated). A successfully designed and conducted CLIL lesson, including a project, should be based on four basic principles, which include content, communication, cognition and culture.

Fig. 1. The historical centre of Toruń and the location of the school area

Fig. 2. Mixed English-French-Polish group of students involved in the exchange posing to a photo in the school yard in Toruń

a. Project content

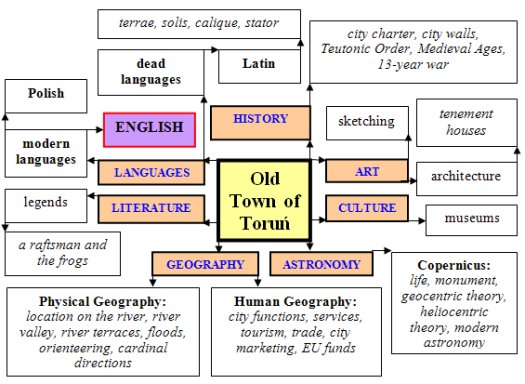

The key element of the project is its content, which means there should be some progress in acquiring the knowledge, skills and understanding connected with the curriculum of the school subjects studied. The centrality of the selected theme and its connection with various core subjects is presented in a form of a mind map (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Mind map – Old Town of Toruń as a theme of an interdisciplinary project

In terms of Geography, both physical and human, doing the project the students practiced their knowledge on how to use cardinal directions and thus developed their orienteering skills. They also made observations on old city functions, such as defensive function, and modern city functions, such as tourism and banking services. There was also an opportunity to revise the heliocentric theory of Copernicus.

The content in History concentrates on Middle Ages, as at that time the city layout with a planned street pattern was created. The students learnt some facts from the city’s history, such as the 13-year war with the Teutonic Order, and the way the city functioned in the past, e.g. by looking at the defensive walls and the tenement houses.

Although Toruń’s Old Town originated in the medieval times, besides Gothic a whole range of architectural styles are represented there. Thus, as far as History of Art was concerned, the main content students learnt were the examples of different styles in architecture (Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque and Art Nouveau). Moreover, the students were asked to sketch some of the buildings on the given handouts in order to study the elements characteristic for the given architectural styles.

The project also included some elements of Astronomy (Copernicus and his deeds), Literature (a legend about a raftsman and frogs), Latin (inscription on the monument of Nicolaus Copernicus) and Culture (city symbols, museums).

b. Project communication

Communication element of the project in a foreign language means that besides the content there is the language there to learn. This is most successfully done while interacting with other people, be it a teacher or peers. As the project was originally designed for a mixed Polish-English-French group with English as the language of communication, for the Polish students it served as an intensive language skills practice. They included reading the directions, speaking and listening while discussing the answers, and writing those answers down. The project also included a whole range of vocabulary specific for the content studied, such as heliocentric theory, city charter, cardinal directions (Geography), moat, city walls, Teutonic Order (History), Gothic, 16th-century ceiling decorations, rich floral decorations (History of Art and Art).

c. Project cognition

Cognition means abstract and concrete concepts should be combined with understanding and language, and result in developing thinking skills. In terms of this project, thinking skills were achieved by integration the language and the contents, and drawing conclusions from the direct observations.

d. Project culture

Cultural aspect of the project means students should be exposed to alternative perspectives and shared understanding, which in turn develops awareness of otherness and self. By interacting during the interdisciplinary project, all groups of students had a chance to learn about people from other countries. Moreover, by working in pairs students developed their social and co-operative skills.

The project was designed to last two hours. In that time the students worked in mixed English-French-Polish groups (Fig. 4)

Fig. 4. Two teams of students sketching one of the tenement houses

Below there is a set of various project tasks ordered in terms of their leading feature, i.e. Geography, History, History of Art and Art. In reality, however, all the tasks were mixed, as at every place the students were asked to stop a whole range of different observations were expected. Sometimes, thus, it is difficult, or even impossible, to tell a Geography task from a History task, and the other way round. Originally, the project did not include the photos. They have been added here to give the readers an idea what Toruń looks like. The forms are completed with the answers given in blue italics.

a. Selected tasks in Geography

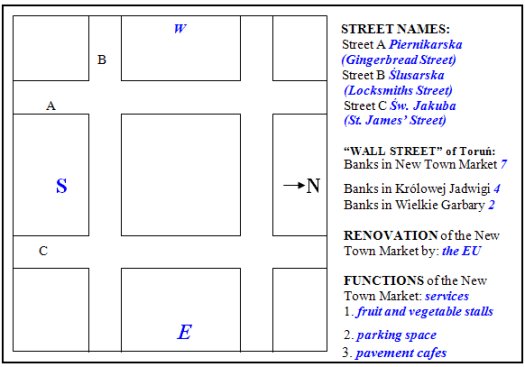

Example 1: Stop I – New Town Market

- The market has a very specific carefully planned layout. Complete the drawing (Fig. 5) with the names of the streets. The names of the streets are also monuments today. What do the names of the streets A, B and C mean?

- In the drawing insert the missing cardinal directions (E, W, S).

- The market has recently been renovated (Fig. 6). Find the board saying who gave the money.

- The market and the adjoining streets have become the ‘financial district’ of the city. While you walk around count all the banks and other institutions lending money to people.

RENOVATION of the New

C Town Market by: the EU

FUNCTIONS of the New Town Market: services

1. fruit and vegetable stalls

E 2. parking space

3. pavement cafes

Fig. 5. The handout section with the New Town Market street layout

Fig. 6. The recently rejuvenated New Town Market

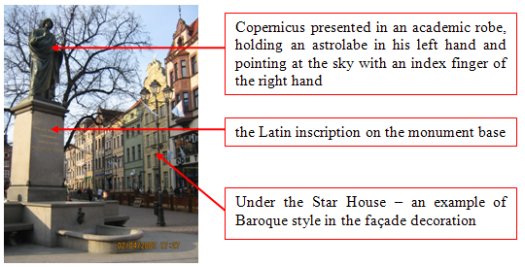

Example 2: Stop III – The Old Town Market – Copernicus 1

There is a characteristic monument in the market (Fig. 7). Read the inscription in Latin and translate it into English (Nicolaus Copernicus Thorunensis. Terrae motor, Solis Caelique stator)

Nicolaus Copernicus, the citizen of Toruń, set the Earth in motion and brought the Sun into a halt

2. What does the inscription mean? What does a heliocentric theory say? The Sun in the centre of the Solar System with the planets moving around

3. Can you decipher the years he was born and died in (MCDLXXIII and MDXLIII)?

Born in 1473; died in 1543

Fig. 7. The monument of Nicolaus Copernicus in the Old Town Market in Toruń

b. Selected tasks in History

Example 1: Stop II – The Teutonic Castle

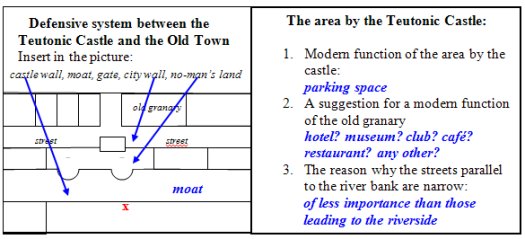

- You have just walked across the terrain which once belonged to the Teutonic Castle. The buildings you see in the distance belong to the Old Town of Toruń, while the building behind you – to the New Town of Toruń. The Castle area separates both cities as a kind of a wedge. Complete the drawing of the defense system between the Castle and the Old Town (Fig. 8).

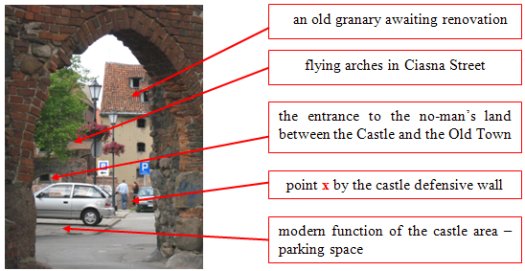

- The large building in front of you needs renovation badly (Fig. 9). It was once used as a granary (place for storing grain). How should the building be used once it has been restored? Give your suggestion with the arguments.

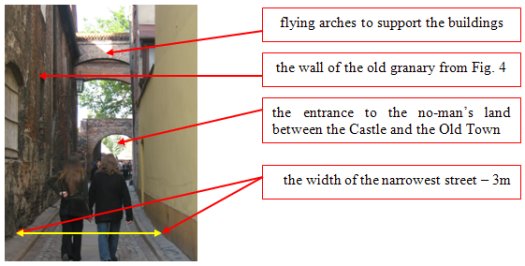

- Ciasna Street to the left of the large granary is very narrow (Fig. 10). In fact it is the narrowest street in the city (only 3 meters). Generally, the streets parallel to the river are much narrower than those which lead to the riverbank. Can you guess why?

Fig. 8. The handout with the layout of the defensive system between the Teutonic Castle and the Old Town

Fig. 9. The view through the castle gate at the Old Town buildings and the defensive system between the Old Town and the Teutonic Castle

Fig. 10. Ciasna Street, the narrowest street in the Old Town

Example 2: Towards the Leaning Tower and the Old Town defensive walls

Before you leave the Town Market walk up the Post Office building and measure one 19th-century brick (Fig. 11).

Answer: The 19th-century brick is 12.5 cm long and 7 cm thick.

Now you leave the Town Market. Walk past the church towards the street called Różana (Rose) – it was named like that as it was actually really smelly! In the distance you see three buildings with a kind of a passage under. Walk there. What kind of public transport was used there? When?

Answer: The public transport used in the city centre in the past trams (first horse-drawn, later electric)

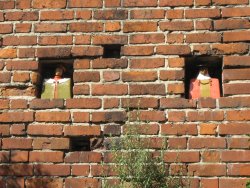

Walk under the buildings and turn left. Go towards the remains of the medieval city wall in Pod Krzywą Wieżą Street. Walk up the wall. It was built in the 14th century. Measure one brick (Fig. 12).

Answer: The 14th-century brick is 30 cm long, 15 cm wide and 9 cm thick. One medieval brick weighs 7 to 10 kg and the brick layers had to use both hand to lay them properly!

Fig. 11. The wall of the 19th-century Post Office

Fig. 12. A fragment of the medieval wall

c. Selected tasks in Art and History of Art

Example 1: Tenement houses in Szeroka Street

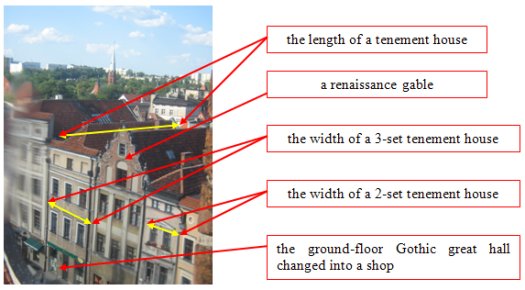

The tenement houses in the Old Town are very narrow but they are very long inside. Due to scarce land within the city walls, the land was very expensive. Thus, the width of the buildings depended on how rich the owner was. Today, although the façades of the tenement houses differ, the very walls are of medieval origin (Fig. 13). Go into the shoe shop ‘CCC’ in Szeroka Street. How will you calculate its length and width of the building? (steps)

Answer: The ‘CCC’ shoe shop is about 29.2 m long and about 3.6 m wide.

Walk upstairs to find the 16th-century ceiling decorations.

Answer: The ceiling in made of wood and has floral decorations.

Fig. 13. A row of tenement houses in the Old Town Market – the view from the Old Town Hall window

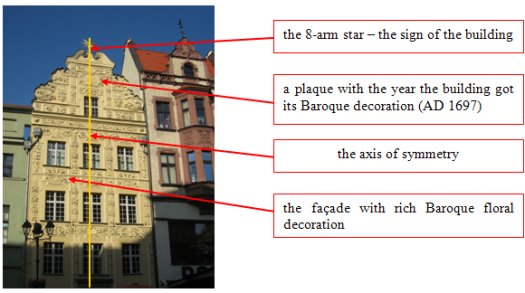

Example 2: The star house

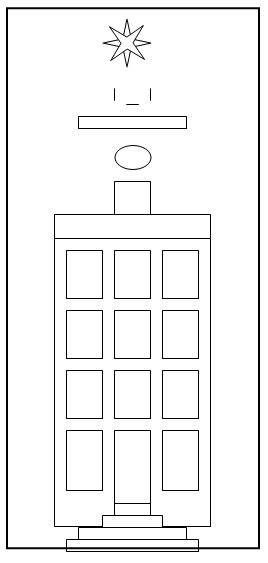

Walk straight past the monument of Nicolaus Copernicus. On the right you can see a yellow building with rich floral decorations and a green star on the top. This tenement house is called Under the Star House (Fig. 14). It was originally built in medieval times, but had its façade decoration changed completely into rich floral Baroque style in 1697. Note this style uses symmetry. Use the given handout to complete the drawing of this tenement house’s decoration (Fig. 15).

Fig. 14. Under the Star House

Fig. 15. The handout to draw Under the Star House

The project designed for the exchange students proved to be successful and enjoyable, as commented on by the students themselves, although not all the groups managed to complete all the tasks. In fact, this was not the aim to get everything done, as the activity also served as a socializing event. Moreover, originally it was quite hard to decide how much time to devote to the project and how much material to include. As Toruń’s Old Town is a place full of interesting sights, the selection of the most important objects seemed crucial so as not to overload the project with information. The completed forms served as the feedback for the author and will be used in further work on the project content.

Interdisciplinary projects, as the one described in the paper, bring organisation problems. However, the involvement of the students and their gains make such projects indispensable in modern school practice, especially if combined with foreign languages acquisition,

Bailey P. (1991), Zajęcia terenowe w Lubiczu Górnym, Geografia w Szkole, nr 4

Brown K., Brown M. (1996) New contexts for modern language learning: cross-curricular approaches, Pathfinder 27. CILT; excerpts available from:

www.phedw.at/_intnati/sokrates/cdibit/ accessed 05/12/2007

Coyle D. (2000), New Perspectives on Teaching and Learning Modern Languages, Simon Green (Ed.), Multilingual Matters, chapter 9: Meeting the Challenge (pp. 163-170); excerpts available from: www.phedw.at/_intnati/sokrates/cdibit/ accessed 05/12/2007

European Union Position on CLIL and Training for CLIL (undated), www.factworld.info/materials.htm, accessed 15/09/2006

Fried-Booth D. (1997), Project Work, Resource Books for Teachers, Oxford University Press, Oxford

Gołebniak B. D. (2002), Uczenie metodą projektów, WSiP SA, Warszawa

Kelly K. (undated), What does a successful CLIL course look like? Experiences from secondary CLIL teacher training, PowerPoint Presentation, accessed 05/12/2007

Pikulski J., Cooper J. (undated), Issues in Literacy Development

www.eduplace.com/rdg/res/literacy/, accessed 07/01/2008

Zaparucha A. (2006), Projekty w nauczaniu geografii, Geografia w Szkole, vol. XI-XII

Zaparucha A. (2007a), How much English Teaching in Geography Teaching, In: Geography in European higher education, vol. 4: Teaching in and about Europe, HERODOT Network

Zaparucha A. (2007b), Teaching Geography through projects: a European and linguistic dimension, In: Geography in European higher education, vol. 4: Teaching in and about Europe, HERODOT Network

Zaparucha A. 2008, Student Projects for Geography and English Integrated Learning [in: K. Donert, P. Charzyński, Z. Podgórski (eds.) Bilingual Geography – aims, methods and challenges], HERODOT/SOP, Toruń, pp. 58-90

Please check the Teaching English Through Music & Art course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Creative Methodology for the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the CLIL for Secondary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the ICT - Using Technology in the Classroom – Level 1 course at Pilgrims website.

|