Acquiring Expressions through Texts for Children: Lexical Approach with Young and Very Young Learners

Zhivka Ilieva, Bulgaria

Menu

Introduction

Chunks in the process of teaching and learning a foreign language

Using texts for children in teaching young and very young learners to build a stock of whole phrases

Games for acquiring expressions based on texts for children

Conclusions

Children’s literature (rhymes, songs, stories, picturebooks) is a rich linguistic resource for foreign language teaching (FLT). Through these texts young learners easily acquire structures above their actual level of linguistic development in the foreign language.

Texts for children are a suitable material for implementing the lexical approach with young learners. With very young learners we rely on oral work and memorizing in class. When we read a book to the group or when we sing and recite together, children remember the text no matter how complex the structures are.

It is a good idea to avail of the young learners’ ability to memorize children’s literature texts in foreign language education. Hill (2000: 48) observes that “…children learn huge chunks of lexis, expressions, idioms, proverbs, nursery rhymes, songs, poems, bedtime stories without necessarily understanding each word. … in learning such chunks they are also acquiring the pronunciation, stress, and intonation patterns which will remain with them throughout their lives. They are also learning the grammatical system of the L1.”

The lexical approach relies upon the natural ability of the learner to remember whole phrases uniting the vocabulary and the grammar material that has to be taught. According to Lewis (1993) language consists of chunks that form the texts. Therefore it is advisable to teach the whole chunks and not isolated words. In Willis’s (1990) opinion the lexical approach does not describe language functions or grammatical structures but words with certain meanings given in their usual surroundings.

In another publication Lewis (2000 b: 181) states that “…phrases are easier to remember than words; breaking things into smaller pieces does not necessarily make them simpler, and … understanding is not enough to ensure that input becomes intake. This means teachers need to be proactive in helping learners develop an increasing understanding of the lexical nature of the language they meet and be more directive over which language is particularly worth special attention.” Young learners are too young to write down phrases but they love recycling them in the context of a story, song, rhyme, or while ‘reading’ a picturebook.

Lewis (2008: 47) recommends developing strategies for dealing with unknown items met while listening or reading and “the ability to guess on the basis of context, situation or lexical clues.” The presentation of rhymes and stories is usually richly visualized by pictures, toys, etc. The suggested songs are animated clips in youtube, i.e. they are also well visualized. Using a book also creates context for easy understanding. Kaminski (2013: 19) finds out that working with picturebooks “the children scan the pictures for clues and actively construct meaning from them.” They are “able to jointly reconstruct the storyline 12 months after their first and only encounter with the picturebook. … one encounter with this picturebook helped to create a meaningful context, within which vocabulary knowledge can be expanded during repeated encounters with the story.” (Kaminski 2013: 19)

While listening to various stories, songs and rhymes the children meet some of the same words in new expressions and in Woolard’s opinion (2000: 31) “learning more vocabulary is not just learning new words, it is often learning familiar words in new combinations.”

According to Lewis (2000 a: 150) the students “need to know what structure follows a verb (an infinitive or gerund for example) and what preposition it goes with.” The suggested games offer examples of come to (play with …), other stories illustrate like + -ing. Young learners do not know the rule, in another context they may use like + another form or play + -ing, but once they have remembered the formula and worked with various fillers of its slots, they have the basis for further work and for drawing conclusions and learning the rules at a later stage.

Research shows that repeating the same task in a variety of ways (for example, giving the same talk to different groups) leads to “improvement in fluency”, to “both grammatical and lexical improvement” (Hill et al 2000: 91). Young learners do not give long talks but listening to the same story and taking part in it and the activities connected to it many times has the same role.

Children are always keen on talking – they are eager to show how successfully they can use the little language they have mastered. That is why I include in the next part of the article games that provide opportunities for the learners to form similar sentences to the ones they have met in the book or in a rhyme. They enjoy this kind of drilling, they feel they take part in the storytelling process and gain confidence they can say something in English – a whole sentence!

Children use whole phrases from stories in their native language. A 2-3 year old girl is playing with her aunt. The aunt takes the other end of the toy held by the girl and asks kindly “please, give it to me.” The girl pulls the toy back and says “no”. They continue this way and the aunt remembers the story about the blackbird the girl knows. After repeating a few times with various intonation and voice “please, give it to me” “no”, the aunt says “If you don’t give it to me…” and the kid adds “You’ll eat me up” (in her baby pronunciation). They burst out laughing. Children love stories and love incorporating them in their everyday play.

This example comes as an illustration of Davis’ (2013) observation that “Insights into how we learn our mother tongue confirm that we learn it through such chunks which get gradually stored in our heads and retrieved when needed. … These chunks are then used to string utterances together, and grammar is wound around them.” It is also a confirmation of Hill’s opinion that “Collocation allows us to think more quickly and communicate more efficiently. Native speakers can only speak at the speed they do because they are calling on a vast repertoire of ready-made language, immediately available from their mental lexicons.” (Hill 2000: 54). This is the reason why we decided to work with suitable texts with foreign language learners from an early age.

In the opinion of Hill et al (2000) in order to acquire a word, learners have to meet it several times. They (Hill et al 2000: 99) state that “it is often more effective to work not on brand new, but on relatively new vocabulary if words which are known passively are to become available for learners’ active use.” Most stories and children’s books are repetitive. Multiple repetition and the follow up activities aid remembering. Sometimes different stories illustrate the same words in various expressions e.g. lost his mitten (The Magic Mitten, Konstantinova 2001) and a pair of mittens (Goodnight Moon, Brown 1996); a pair of shoes in the activities after Goodnight Moon and could tie his shoes (Franklin and the Tooth Fairy, Bourgeois 1999). McCarthy et al (2010: 25) confirm this in the following way: “In context the word has meaning which is linked to other words that the learners already know and it is part of the schema of the story. This will make it more memorable as well as more accessible.” Stories and books for children are part of the young learners’ world and create a memorable context. Moreover Michael Lewis (2000 b: 182) states that “In general, learners are more likely to acquire new language in such a way that it is available for spontaneous use if it is incorporated into their mental lexicons as an element of some comparatively large frame, situation or schema.” Texts for children provide the large schema and the successive activities ensure repetition and remembering.

Children love listening to stories and interacting with picture books while being read to. Davis (2013) points the usefulness of reading aloud – it “forces learners’ awareness of the importance of intonation in conveying meaning.” With young and very young learners the teacher reads aloud and the children enjoy the story, pick up words and phrases and the reader’s intonation and ways of expressing meaning (e.g. body language). This way they enrich their social and communicative competence (Canale and Swain 1980) and by remembering the whole story – their collocational competence (see Hill 2000).

As Lewis (2008: 51) stresses it is unquestionable that language level is improved “by learning new things, and doing new texts, activities and exercises.” Texts for children provide a rich medium for activities aiming at the acquisition of whole expressions.

Activities over children’s books

Here we offer chosen sentences from books suitable for young and very young learners that can be drilled as a frame with one or more slots in the form of a game.

• Activities for very young learners

The book Mine (Baxter 2002) is suitable for being read to very young learners. Some of the sentences can be developed as a while reading activity and others as a post-reading activity.

“Piles of picture books” turns into piles of toys, piles of chocolates etc. with the help of pictures. The teacher shows a picture and the children form the corresponding sentence.

The sentence “Barney likes playing with all of them.” can be changed in the following way: He likes playing with the drum / the cars / the train / the lorry / the plane / the ball / the teddy bear – each time a different picture is shown to the group.

The sentence “One day Barney’s cousins Georgia and Luke come to play.” provides opportunities for two games: the one practising the animals in singular and the 3rd person singular –s ending in the present simple tense, the other practising the plural subject and the 3rd person plural present simple.

- The teacher introduces the game: “Let’s see who comes to play with us” and answers “The giraffe comes to play with us!” showing a giraffe toy.

The teacher shows different animals (toys) and supports the learners in forming the sentence The bear / wolf / fox etc. comes to play with us.

- Another day the plural is practised with the help of pictures (paper or digital ones).

The giraffes come to play with us.

The bears come to play with us.

The boars come to play with us etc.

In these games the children think they practise animals’ names but in fact they practise structures (the present simple tense) and are ‘tested’ on animals.

The sentence “Georgia plays with some blocks.” is a basis for a few games:

- The giraffe plays with some books / cars / lorries / planes etc.

During the first game only the object is substituted. The children practise the indefinite pronoun some with a plural noun.

- The bear / wolf / kangaroo etc. plays with some books / cars / lorries / planes etc.

During the second game the subject of the sentence is also substituted. The learners revise animals and vehicles. In this example two slots are open.

- The giraffe plays with the monkey / the hippo / elephant etc.

During the third game the object is changed – this time the kids say who the giraffe plays with and not what it plays with.

- The giraffe plays with a car / a plane / a train / a bicycle.

During the fourth game the accent is again on what the giraffe plays with practising the use of a singular noun with the indefinite article.

For all these games we use pictures of animals and toys.

“I’ve got something nice for you in the kitchen.” sets a context for two games:

- I’ve got some icecream / pizza / chocolates / apples / bananas / vegetables etc. for you.

The first game practises the indefinite pronoun some + a plural or an uncountable noun. The order of appearance of the nouns is determined by the pictures shown.

- Later on the sentence is developed with the adverbial of place. This time a singular noun with an indefinite article can be used.

I’ve got a book for you in the living room.

I’ve got a new toy for you in the corridor.

I’ve got a new shirt / dress / skirt / T-shirt for you in the bedroom.

This way the rooms in the house, clothes and toys / animals are revised with the help of pictures.

“He comes back with a teddy bear…”

He comes back with a car / a train / a plane etc. (all kinds of toys).

Children adore reading the story again and again. They also love the games accompanying it. We spare a few minutes at the end of the lesson for reading the book developing the story playing some of the games. The children learn the phrases. These ideas can be realized with other stories suitable for very young learners. The suggested games are for learners from four to eight years old who do not write and read in the foreign language yet.

• Activities for young learners

The story of Franklin by Paulette Bourgeois (1999) is suitable for primary school students. It is introduced at the end of the first term or the beginning of the second term with second grade students. They have already been introduced to the modal verb can through the story The Warm Mitten (Blue Skies for Bulgaria, Holt 2007: 78-81). This Franklin book is usually introduced one page per lesson excluding the last two which are always read together. This means 14 classes. Since the story is long, we do not always start from the beginning. We either introduce only the new page or 2 or 3 pages from the previous lessons + the new one and an activity – no more than 5-10 min. per lesson.

The first sentence of Franklin and the Tooth Fairy provides an opportunity to practise Can you (count by twos, count up to five, read books, sing, dance, write, swim, etc.)? and I can … The second stage of practising the pattern is opening two slots for a change (the personal and the possessive pronouns):

Can you tie your shoes? I can tie my shoes.

Can he / she tie his / her shoes? He / She can tie his / her shoes.

This way the students practise questions and answers with the modal can and sequencing pronouns (I – my, he – his, she – her).

Another pattern is I / We / They have lots of books / toys / pencils / stamps / clothes revising the corresponding vocabulary.

The third pattern is We like the same books / films / toys / games.

The task is usually set in the children’s native language: In pairs discuss with your partner if you like the same games, books, films, toys (it may be done in the native language) and report in English the same things you like; an example is given.

At the second stage of this activity (realized during another lesson) the patterns used are two or three: We like the same books; We don’t like the same books; We like different books. The students have support on the board – some of the items they are going to talk about and the structures.

In pairs the students practice the conversation:

I lost my … (wallet, ruler, rubber, pen, pencil, notebook, student’s book, activity book, bag, bike, skateboard, ball, umbrella etc. (shown by pictures or realia).

Wow! How are you going to tell + object (e.g. the teacher)?

This activity reinforces vocabulary from the student’s book.

The next activity is again pair work – the students practise

What’s wrong?

I don’t have any … (books, pencils, etc.)

The students use the indefinite pronoun any and practise vocabulary and a social expression.

Another dialogue suitable for role play is

What does the _____ do with all those/these books?

I don’t know but he/she always leaves something behind. He/She always leaves a __.

Does ____ leave a book?

According to Usher (2013) through role play “students become more confident in expression given the opportunity to independently activate their minds in working themselves with the words.”

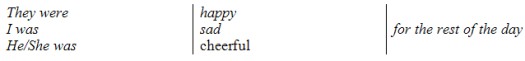

Practising verb + adverb of manner with the help of pictures (we can use emoticons):

said sadly / happily

Sentences of the type S link verb Cs + Adv.:

Another sentence that can be practised and later on used as a formula is

All his friends… looked at him/me with amazement/disgust

Songs and rhymes for both young and very young learners

There is a great variety of songs accessible on the internet.

Through songs children in the kindergarten acquire greetings and politeness expressions (for example Hello Song for Children, The Greeting Song (see the resources list) and other similar ones).

They easily acquire Do you like …? Yes, I do. No, I don’t. through the song Do You Like Broccoli Ice Cream? (from supersimplelearning.com – see the resources list). They enjoy making more absurd combinations of the type cabbage cake or salad ice cream.

With the song How’s The Weather? (supersimplelearning.com) they acquire question structures and with the follow up activities (e.g. conversations at the beginning of each lesson), they start turning questions into statements. We usually introduce statements first and general questions after that, but adding variety is always useful and breaks the routine.

The rhyme On the Farm finishes with the sentence “All these animals you can see if you come to the farm with me”. We can change the animals and the final sentence to become if you come to jungle / zoo with me. This way the children acquire “if” structure – too complex for young learners but easily acquired through the rhyme. At the same time they enjoy the idea of creating a new similar rhyme with the animals they themselves choose.

e.g. Hippos, elephants, rhinos, too

Zebras, giraffes, lions, wow!

All these animals you can see

If you come to the zoo with me

The children who knew the song My New Shoes (Koeva 2002: 39), usually sung at first grade and in kindergartens, coped better with the pattern I can tie my shoes. Even a girl sang tie, tie, I can tie my new shoes. This supports my opinion that children acquire language better (both lexical and grammatical patterns) if taught through texts and not word by word.

In the primary school this kind of work gave the children whole expressions and formulae where they revised and reinforced the vocabulary from the student’s book. The exercises connected to story building provided space for their creativity and gave them a reason to feel proud of their own achievement in English. This heightened their motivation.

Texts for children are usually translated the first time they are introduced for the learners to understand their meaning. Translation and understanding are part of the lexical approach as well as repeating the text and some of the activities a number of times. Children love repeating again and again songs, rhymes and stories, being read many times the same book which gives opportunities for reinforcing the expressions and doing the same activities with a little change – to acquire the frame with different fillers.

Learners at this age do not read and write fluently in English yet. They cannot have their lexical notebooks but they acquire whole chunks of language and with appropriate activities they gradually break the formula, open more slots and use the long or complex expressions in various situations and enjoy it.

This lays sound basis for their future foreign language education – they will be used to receiving the language in whole chunks. The acquired expressions are easily included in conversations. The vocabulary stock built at this early age by whole phrases serves as a source for drawing conclusions about the language, as an illustration of the grammatical rules when they are introduced at the later stages.

The activities suggested can be adapted to any text and various age groups.

Canale, M. and M. Swain, (1980) Theoretical Bases of Communicative Approaches to Second Language Teaching and Testing, Applied Linguistics, 1, pp 1-47.

Davis, P., (2013) The Company Words Keep, Humanizing Language Teaching, 15:6, Dec. 2013 old.hltmag.co.uk/dec13/index.htm http://old.hltmag.co.uk/dec13/less04.htm

Hill, J., (2000) Revising priorities: from grammatical failure to collocational success in M. Lewis (ed.) Teaching Collocation: Further Developments in the Lexical Approach, Hove: Thomson Heinle, pp. 47-69.

Hill, J., M. Lewis and M. Lewis, (2000) Classroom strategies, activities and exercises in M. Lewis (ed.), Teaching Collocation: Further Developments in the Lexical Approach, Hove: Thomson Heinle, pp. 88-117.

Kaminski, A. (2013) ‘From Reading Pictures to Understanding a Story in the Foreign Language’ in CLELE Journal – children’s literature in English language education, 1/1: 19-38.

Lewis, M., (1993) The Lexical Approach, Hove: Language Teaching Publications.

Lewis, M., (2000 a) Language in the lexical approach in M. Lewis (ed.) Teaching Collocation: Further Developments in the Lexical Approach, Hove: Thomson Heinle, pp. 126-154.

Lewis, M., (2000 b) Learning in the lexical approach in M. Lewis (ed.), Teaching Collocation: Further Developments in the Lexical Approach, Hove: Thomson Heinle, pp. 155-185.

Lewis, M., (2008) Implementing the Lexical Approach: Putting Theory into Practice. Andover: Heinle, Cengage Learning.

McCarthy et al (2010) M. McCarthy, A. O’Keeffe, S. Walsh. Vocabulary Matrix. Understanding, Learning, Teaching, Heinle CENGAGE Learning, Andover, UK.

Usher, R., (2013) Teaching English Vocabulary, Humanizing Language Teaching, 15:6, Dec. 2013 old.hltmag.co.uk/dec13/index.htm http://old.hltmag.co.uk/dec13/sart09.htm

Willis, D., (1990) The Lexical Syllabus: A new approach to language teaching. London: Collins COBUILD.

Woolard, G., (2000) Collocation – encouraging learner independence’ in M. Lewis (ed.), Teaching Collocation: Further Developments in the Lexical Approach, Hove: Thomson Heinle, pp. 28-46.

Resources

Baxter, N., (2002) Mine, London: Bookmart Limited.

Bourgeois, P., (1999) FRANKLIN and the Tooth Fairy, Ontario: Kids Can Press Ltd., Atlas Editions Inc.

Brown, M. W., (1996) Goodnight Moon, New York: HarperCollins.

Do you Like Broccoli Ice Cream? http://supersimplelearning.com/songs/original-series/three/do-you-like-broccoli-ice-cream/ (accessed February 2015).

Hello Song for Children www.youtube.com/watch?NR=1&v=AdukBVPk8Jw&feature=fvwp (accessed January 2015).

Holt, R., (2007) Blue Skies for Bulgaria Student’s Book, 2nd edition. Harlow: Pearson Longman.

How’s The Weather http://supersimplelearning.com/songs/original-series/two/hows-the-weather/ (accessed February 2015).

Koeva, V., (2002) Little Star English for Children. Child’s book II, Plovdiv: Daniver.

Konstantinova, L., (2001) The Magic Mitten in Five Funny Tales About Fellows With Tails. Sofia: Fyut, pp. 7-12.

On the Farm www.canteach.ca/elementary/songspoems55.html (accessed January 2015).

The Greeting Song www.youtube.com/watch?v=gVIFEVLzP4o (accessed January 2015).

Please check the Methodology & Language for Kindergarten Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Methodology & Language for Primary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

|