A Model of Second Language Acquisition Based on Chunks

Manjula Duraiswamy, India

Manjula Duraiswamy has been a Teacher, Teacher trainer and Senior Editor with two different publishing houses. She is an Examiner for the University of Cambridge, Local Examinations Syndicate and is a Language Trainer for corporate clients. She enjoys travel, writing and music and is deeply interested in language development across a variety of contexts. E-mail: manjula92001@yahoo.co.in

Menu

Introduction

Journal entries

The use of chunks by students was studied under five categories

Classroom methodology

What are chunks?

Findings

Conditions for language acquisition

Learner characteristics

Opportunities for second language acquisition

A model of second language acquisition based on chunks

Bibliography

This report describes the use of chunks or sentence fragments in the classroom and explores the feasibility of this methodology in varying classroom scenarios. The aims of the study were to determine:

- Whether chunks methodology could replace current methodology in the classrooms,

- Whether it was possible to develop a uniform syllabus based on chunks methodology

- Whether it was possible to produce uniform teaching material based on this methodology.

The framework took into consideration:

- Students from different backgrounds

- Learners with special needs

- Gifted and talented students

- Achievements objectives

- Assessment

- Literature and chunks methodology

- Criteria for selection of texts

- Focus on language

- Intralingual practise

A wide range of language teaching experiences have formed the bedrock of my research into second language acquisition, investing it with special relevance. It facilitated research and analysis of processes through reflection and action for learners and teachers of English and other languages.

Classroom research builds on the knowledge and experience that teachers have acquired over many years of hard work and persistence and it addresses the immediate concerns of the classroom, being sensitive to the requirements of different kinds of learners. It is an organic process of continuous evaluation and assessment that sharpens teacher understanding and straddles the gap between theory and practice.

My study recognized that all language is an independent interpretation of various inputs and can be a rewarding and stimulating experience for both the learner and the teacher. I investigated the importance of input language in the development of learner competency and focused on classroom practices and ‘noticing’ techniques to take the idea forward.

Data was gathered from a wide range of settings both ethnographic and plural, employing ‘multiple perspective negotiation’ to arrive at an understanding of the model framework for learning that I was developing.

I taught English at Bhavan’s Rajaji vidyashram, Chennai for twelve years, moving with the same set of students from class one to ten. I thus set out on a voyage of discovery with one set of students putting into practice all that I had learned during Child Education and ELT classes and my personal experience with language learning. I maintained a journal to capture the teaching/learning scenario over the years.

Notes on language development across the first teaching experience at class one and the final experience at class ten were included in the journal.

I began teaching class one at Rajaji vidyashram in 1993. I next had direct contact with the same set of students in 1996 when they reached class three. Two years later I had moved up to class five where I taught the same set. In 1998 I had the same set of students in class seven. In 2000 I taught class nine and had ‘my’ set once again. In 2001 I moved with my set to class ten and saw them through the board exams. The class dispersed

after this.

My journal entries on the uses and functions of chunks in second language acquisition were maintained based on the understanding that:

- chunks are syntactically fluid

- their breakdown leads to the development of grammar

- chunks promote fluency

- chunks appear to be stored cognitively and retrieved by speakers as if they were single words.

- they facilitate competence by minimizing and shortening pauses

The journal examined the development of second language production among learners who received practice in chunks.

the repetition and dependence on select chunks

the use of multiple chunks

the complexity of chunks

the use of chunks as mere fillers or rhetorical devices

the accuracy of use

The actual teaching programme revolved around choices based on an initial assessment of learners and their needs. A selection of lessons from the course book and independent texts based on interest and appropriacy were finalized and each unit was exploited for meaningful sentence fragments. These ‘remembered fragments’ formed the basis of language learning as the recycling of language is inherent with understanding how grammar systematically coordinates and manages language output. The study was an exploration of the form-meaning focus of classroom language teaching that is the actual condition of the language classroom.

The classroom methodology of this approach followed these five stages:

- Observation- In this stage attention is focused towards features of language incorporated in the chink through activities involving ‘noticing’ and real-life language experiences. The learner has direct experience of language in use.

- Hypothesis- This stage helps the learner navigate through language, finding explanations for linguistic phenomena involved in a piece of text. In short, the learning of grammar rules is facilitated through an understanding of patterns of language use; the learner forms an impression of the way language items work in different contexts.

- Experimentation- The learner now confirms understanding of language learnt through exploratory language use in carefully scaffolded context.

- Consolidation- The learner reformulates and trials structures in different context.

- Internalization- The learner relates language use to appropriate grammar terminology and understands the way language works.

Classroom methodology for chunks includes these steps:

- Teacher managed ‘noticing’ activities in the classroom

- Group work with a set of pre-determined chunks (gap-fill and consciousness raising activities involving chunks in different contexts, matching)

- Pair work (creating new sentences using a common set of chunks)

- Whole-class teacher led evaluation of sentences

- Error analyses

- Individual work using chunks in longer pieces of writing

- Display of writing and whole class evaluation.

Chunks methodology promotes knowledge of a language in a natural manner. The table below displays the different stages in knowing a language and the chunks which are used at each stage.

| Stages |

Knowledge of language |

Examples |

| State 1 |

Knowing how to use language for functional purposes |

Can ask for a ticket on a bus:

Ticket please.

|

| State 2 |

Knowing parts of a language |

Can read and understand notices and information brochures

Ticket counter this side

|

| State 3 |

Achieving general proficiency |

Example: He is better dressed than me |

| State 4 |

Ability to convey nuances in meaning |

Example: His clothes show refinement, but are too conservative for my taste |

| State 5 |

Achieving descriptive ability and able to convey feelings accurately |

Example: His clothes have the stamp of the designer and though they do not actually bear designer labels, they yet have an air of distinguished presence. |

Studies in language development in children can be traced on the same lines as the growth of language in humans. Methodologies for language teaching should respond to changing needs, following schematic frameworks constructed by language teaching experts and classroom teachers. Research also suggests that no one approach fulfills all the learner needs that arise from different learning styles, teaching contexts and grammar items.

In chunks methodology, engagement with expressions is the starting point for language acquisition strategies. Johnson (1996) points out that “hints” and “demonstrations (giving grammar information through examples) can be more effective for language learning than “elaborate, abstract and precise explanation”.

Chunks are lexical patterns found in language use. These lexical patterns are variously called ‘lexical phrases', ‘lexical items', ‘multi-word chunks' or just ‘chunks' of language and are an important feature of language use and acquisition as they offer wide scope for language teaching and learning programmes.

Michael Lewis first proposed the viewpoint in 1993 that language teaching should go beyond divisions based on grammar and vocabulary and that language

should be viewed holistically as patterning made up of strings of language. He classified language into four major categories: words and polywords; collocations; fixed expressions and semi-fixed expressions. The key principle of this approach is that “language consists of grammaticalized lexis, not lexicalized grammar” Michael Lewis (1993.)

My study tested the usefulness of chunks methodology in second language learning and it emerges conclusively that chunks methodology enhances language development promoting language ‘acquisition’ over ‘learning’ and that it can be applied across testing boards and types of schools in our country and across a broad band of adult learning scenarios. The study included learners who were native speakers; others who had visited or lived in the UK or the US for a year or more and the majority had studied English at school formally from some point in their schooling.

From the case studies undertaken, I deduced that mastery over the second language is enhanced through ‘noticing’ tasks where students find out for themselves the nature of the chunks selected and understand the grammatical structures involved. In this inductive method, support for language acquisition is provided through scaffolding and demonstration. From my study it became clear that “what learners find out for themselves is better remembered than what they are simply told” (Ellis, 2003). Such discovery processes also promote greater depth of processing and engagement resulting in more significant learning

The study also took into consideration the implications of formal and informal learning as learner experiences from a wide range of learning contexts were examined. The study examined the importance of chunks language learning, leading to the conclusion that chunks improve language ability through enhancement of skill

and knowledge.

The findings from my study indicate that the conditions for language acquisition encompassing a gamut of situations influence the acquisition of English in a variety of ways. The most important conditions appear to be exposure to English in the home from early childhood and intuitive knowledge of language systems gained through the first language. Language proficiency in one language appears to enhance acquisition of English as learners with understanding of the underlying networks of the language system of their mother tongue appear to find it easy to uncover the network of another language when other conditions for learning like opportunity and social conditions are in place.

Apart from conditions of learning, I found that the personal characteristics of learners appear to influence language acquisition through chunks. The characteristics which promote language acquisition include confidence and early exposure and relevant language inputs and opportunities for learning. I found that when learners were nurtured in an academic environment where chunks were used routinely within the home, they acquired language by being analytical and willing to guess. I found that the successful learners learnt in all situations and used a variety of strategies, celebrating language.

They were, moreover, risk takers and explored language through creative use of chunks. When learners used chunks constantly, their understanding of underlying patterns in language was enhanced and ‘mistakes’ provided scope for further development. The use of chunks instilled in learners the confidence to progress further, having already tasted success. In addition, when learners were able to recognize the importance and objectives of language learning rapid strides were made in language development.

Development of second language learning took place optimally when opportunities for learning were enhanced. These opportunities related to comprehensible inputs, sufficient knowledge of the first language and a perceived need to communicate and contact with proficient speakers. Apart from this, ways of noticing special features, through a selection of useful tasks in the classroom to provide, support and scaffolding emerged as being important. I also noticed that the freedom to be silent and the timing of the lesson were critical. Learners required sufficient preparation time and sufficient ideas to make learning effective. Finally, corrective feedback, provided sensitively, led to language development.

While studying language acquisition in a group, it is important to study language learning on an individual basis taking into consideration differing levels of abilities and motivation. The fabric of language finds expression in the network of social phenomena surrounding the individual learner. In other words, macro level knowledge depends ultimately on micro level learning .The significance of individual experiences therefore is of importance as it accounts for language and how to teach it in a variety of circumstances. The study accepts that testing only the end product of a learning period can be counter-productive as the complex formative process fails to be captured authentically and it is unlikely that learners apply the rules of grammar as they speak and understand. The testing and study model should therefore be as complex as the language process itself.

The complexities of second language acquisition do not afford a homogenous view of acquisition but provide insight into useful teaching practices and methodology. Further, a study of the acquisition process reveals that student progress is non-systematic, with some learners making rapid progress while others stumbling through the stages with limited improvement. Given the same information and learning conditions, why do some students achieve native-like facility while others barely manage simple communicative tasks?

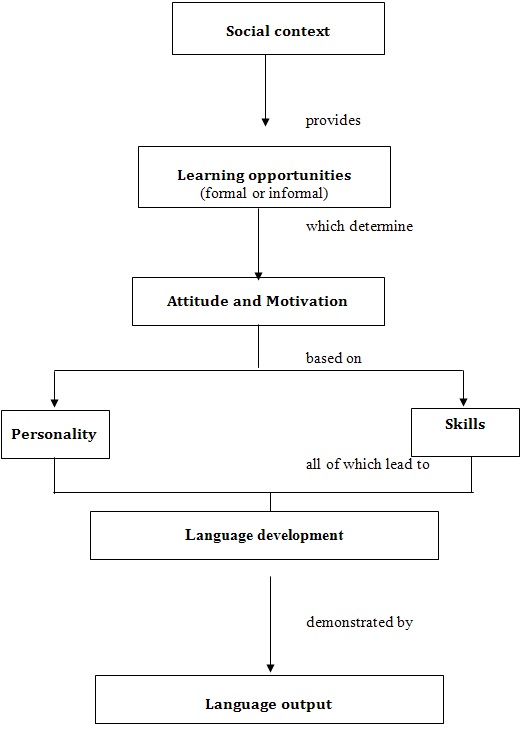

This flowchart for second language acquisition through chunks gives an overview of the processes described.

Aitchison, J. Words in the Mind: An introduction to the Mental Lexicon. Blackwell P, 1987. Print.

---. Linguistics: An Introduction. Hodder Headline P, 1990. Print.

Blum-Kulka, S. Learning to say what you mean in a second language: a study of the speech act performance of learners of Hebrew as a second language. 1982. Print. Applied Linguistics.

Bolitho, R and B Tomlinson. Discover English. London: Heinemann P, 1980. Print.

Bolitho, R. Carter, R., Hughes, R., Ivanic, R., Hitomi, M., Tomlinson, B.Ten Questions about Language Awareness, OUP. 2003. Print. ELT Journal.

Breen, M. and Candlin, C.N. The essentials of a communicative curriculum in language teaching. 1980.Print. Applied Linguistics.

Brumfit, C., J Moon and R Tongue (eds.) Teaching English to Children from Practice to Principle. London: Nelson P, 1991. Print.

Bruner, J. The social context of language acquisition. 1981. Print. Language and Communication.

---. Child’s Talk: Learning to use Language. Oxford: Oxford University P, 1983. Print.

Cameron L. Teaching Languages to Young Learners. Cambridge: Cambridge University P, 2001. Print.

Canale, M. and M. Swain. Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching and testing. 1980. Print. Applied Linguistics.

Crystal, D. How language works. London: Penguin P, 2006. Print.

Csikszentimihalyi, M. Finding Flow: The psychology of Engagement with Everyday Life. Basic books P, 1998. Print.

Dulay H., M. Burt, and S. Krashen. Language Two. New York: Oxford University P, 1982. Print.

Ellis, R. The role of input in language acquisition: some implications for second language teaching. 1981. Print. Applied Linguistics.

---. Understanding Second Language Acquisition. Oxford: Oxford University P, 1985. Print.

Gardner, H.E. Frames of Mind: The theory of Multiple Intelligences. Basic Books P, 1983. Print.

Hakuta, K. and Alvarez, L. Enriching our views of bilingualism and bilingual education. 1992. Print. Educational Research.

Hughes, A. Second language learning and communicative language teaching. London: Academic P, 1983. Print. K. Johnson and D. Porter (eds.): Perspectives in Communicative Language Teaching.

Hymes, D. On communicative competence. Harmondswarth: Penguin Books P, 1972. Print. J.B. Pride and J. Holmes (eds.): Sociolinguistics.

---. Towards linguistic competence. 1985. Print. Revue de I’AILA: AILA Review.

Kachru, B.B. The Alchemy of English: the Spread, Models and Functions of Non-Native Englishes. Oxford: Pergamon P, 1986. Print.

Kramsch, C.J. Classroom interaction and discourse options. 1985. Print. Studies in Second Language Acquisition.

Krashen, S. Principles and Practice in Secondary Language Acquisition. Oxford: Pagammon P, 1982. Print.

Lazear, D. Higher Order Thinking: The multiple Intelligence way. Crown House P, 2004. Print.

Lewis, E.G. Bilingualism and Bilingual Education: A Comparative Study. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico P, 1980. Print.

Lightbown, P. Exploring relationships between developmental and instructional sequences in second language acquisition. Rowley, Mass.: Newbury House P, 1983. Print. H.W. Seliger and M.H. Long (eds.): Classroom Oriented Research in Second Language Acquisition.

---. Great expectations: second-language acquisition research and classroom teaching. 1985. Print. Applied Linguistics.

Maley, A. and Duff, A. Literature: A Resource Books for Teachers. CUP, 1980. Print.

---. Drama Techniques: A Resource Book of Communication Activities for language. CUP, 2005. Print.

Methold, K. The Practical Aspects of instructional material preparation, 1972, Print. RELC Journal.

Munby, J. Communicative Syllabus Design. Cambridge: Cambridge University P, 1978. Print.

Myers-Scotton, Contact Linguistics: Bilingual Encounters and Grammatical Outcomes, OUP, 2002. Print.

Oller, J.W. Language as intelligence. 1981. Print. Language Learning.

Pawley, A.and Syder, F.H. Two Puzzles for linguistic Theory: Native-like selection and native – like fluency in Language and Communication. Longman P, 1983. Print. (Ed.) Jack C. Richards and Richard W. Schmidt.

Prabhu, N.S. Second Language pedagogy. Oxford: Oxford University P, 1987. Print.

Quirk R. and H.G. Widdowson. (eds.). English in the World: Teaching and Learning the Language and Literatures. Cambridge: Cambridge University P, 1985. Print.

Scott, W., Teaching English to Children. Longman P, 1995. Print.

Searle, J.R. Speech Acts: an Essay in the Philosophy of Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University P, 1969. Print.

Seliger, H.W. The language learner as linguist: of metaphors or realities. 1983. Print. Applied Linguistics.

Stevick, E.W. Images and Options in the Language Classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University P, 1986. Print.

Thornbury, S. Slow–release grammar. 2009. Print. ETP. Cambridge: Cambridge University P, 1998. Print. B. Tomlinson (Ed.) Materials Development in Language Teaching.

Widdowson, H.G. Explorations in Applied Linguistics 1. Oxford: Oxford University P, 1979. Print.

---. Discussion. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University P, 1984. Print. A. Davies. C. Criper, and A.P.R. Howatt (eds.): Interlanguage.

Wong-Filmore, L. When does teacher-talk work as input? Rowley Mass: Newbury House P, 1985. Print. S. Gass and C. Madden (Eds.) Inupt in Second Language acquisition.

---. Second language learning in children: A proposed model. 1985. Print. R. Eshch and J.

Wray, A. Formulaic language and the Lexicon. CUP, 2002. Print.

Please check the Methodology and Language for Secondary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the How to be a Teacher Trainer course at Pilgrims website.

|