Editorial

This article was first published in English Teaching Professional Issue 61, March 2009

Fun for Everyone!

Simon Mumford, Turkey

Simon Mumford teaches EAP at Izmir University of Economics, Turkey. He has written on themes including using stories, visuals, drilling, reading aloud, and vocabulary, is especially interested in the creative teaching of grammar. E-mail: simon.mumford@ieu.edu.tr

Menu

Introduction

Hopscotch sentences

Card story

Rock, paper, scissors variation for in, at, on

Driving instructor Simon says

Noughts and crosses drill

Verbal Wink murder

Twenty tag questions

Coin toss

Guess the total

Boxes

Conclusion

There are some well-known, non-language games that students would probably like to play in class, but which do not justify themselves in terms of language practice. With a bit of thought, we could, however, adapt these games for the purposes of language learning. Also, traditional language games that have perhaps become overused and overfamiliar can also be modified to give them a new lease of life. Adapting games for language learning creates the opportunity for a greater range of motivating activities, combining fun, familiarity and effective practice.

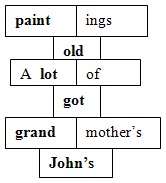

This children’s game involves alternately jumping and hopping from square to square along a grid. Instead of numbers, a sentence, for example John’s grandmother’s got a lot of old paintings, can be chalked on the floor as follows:

The aim is simply for young-at-heart learners to jump on the squares with one and two feet alternately, saying the words as they land on them. Each jump takes the same amount of time, regardless of whether one or two feet touch the ground. Similarly, the words in each jump take the same amount of time to say, regardless of the number of syllables, since only one is stressed (use coloured chalk for the stressed words), helping students produce correct stress

Deal out one pack of cards per group of four to six. Each group makes up a story one word at a time, as follows: the person with the two of clubs starts, playing the card and saying the first word, e.g. Yesterday. Students play cards in numerical order, (3,4,5,6 etc.) regardless of suit. The first person to play an appropriate card and simultaneously say a single word that continues the story in a grammatically correct way wins each turn. Continue with Ace, 2,3,4 after the king each time until one person finishes all their cards and wins.

If you don’t know the original game, it doesn’t matter, as you can still do this preposition version following the instructions here. Instead of the rock, paper and scissors gestures, the two players make symbols for one of the prepositions at, on or in as follows: at =each index finger pointing to the other to indicate a point, on =one finger pointing down on a flat hand, in = one finger pointing into a cupped hand. A third person counts one, two, three and then says a location e.g. the corner, the moon, my mother’s house, the ceiling, the park, the bus stop, the entrance, the pool, London. The players make their gestures at exactly the same time. The winner (if any) is the one whose gesture represents the correct preposition for the place. This is a fast game, with no thinking time; the learning comes in understanding which gestures and time expressions match.

For this version of the game Simon Says, the teacher, in the role of the driving instructor, gives instructions, such as look in the mirror/signal left/change gear/look to the right/left/look behind you/switch the ignition on/adjust the mirror/brake now/wave and smile/put your seat belt on/stop the engine/put the car in neutral/slow down/speed up/open the window/sound the horn/open the door/turn left/right. In the original game of Simon says, students only perform the action if the request is preceded by the words Simon says, and anyone who performs it at the wrong time is ‘out’. In this version, they only perform the action if it is preceded by the request in the form Could you just...? This is appropriate since the learner-driver, a customer, should be treated with respect! Other specific Simon says situations can be used, such as doctor and patient, teacher and student, film director and actor, boss and secretary, etc.<

| If | I | had |

| seen | him | I’d |

| have | introduced | myself |

Draw the grid on the board, with a nine word sentence, and drill it. Now erase the words and use the empty grid for a game of Noughts and crosses. Playing in pairs, players nominate squares by saying the word which occupied it, ie they have to remember the order of words in the sentence. For example, to nominate the centre square, a student says him.

In the original game, a murderer is secretly appointed and this person has to ‘kill’ people in a group one by one by winking at them, without being seen by the others and being unmasked as the murderer. In this variation, the murderer uses a ‘killer word’.

For a group of seven, distribute pieces of paper which read: killer word= biscuit (for the murderer), biscuit 1(for victim 1), biscuit 2 (for victim 2), biscuit 3 (for victim 3), and 3 blanks. The group starts a general conversation, and the murderer has to introduce the word biscuit three times, as naturally as possible. One victim ‘dies’ each time, according to the order given (they can do this by falling over, clutching their throats or by using any other dramatic gesture to indicate that they have been killed). The others listen for the ‘killer word’ and guess the murderer. The victims do not reveal the ‘killer word’ and only ‘die’ when the murderer, and no other person, says biscuit. They must wait ten seconds before dying, so as not to make it too easy.

This is the same as the original twenty questions game (the students have 20 chances to guess a chosen object or person), but with tag questions. Early in the game, students use negative statements with positive tags and tentative intonation to show uncertainty: It isn’t black, is it? Later, when they feel more certain, however, they use positive questions with negative tags and confident intonation: You use it for writing, don’t you?

Asks the students to practise the following dialogue:

S 1: Who is going to do the washing up? Let’s toss for it. You call. (tossing a coin)

S 2: Heads.

S 1: It’s tails.

S 2: OK, I’ll do it.

Continue with wash the car/do the shopping/take the dog for a walk/fix the shelf/take the cat to the vet/sew a button on my shirt/do the ironing/vacuum the carpet. Get students to use a real coin, and explain that the loser has to offer to do the job.

This illustrates the difference between going to and ‘ll. Student 1 uses going to because the job has to be done in the future by somebody. However, as neither person wants to, no offer is made until someone loses the toss and has no choice.

Write the sentences of different lengths on the board as below (in this example they practise the present perfect). Drill then erase them, perhaps leaving the first letter of each word as prompts.

Lived in London. (3 words)

I’ve lived in London. (4 words)

I have lived in London. (5 words)

I have lived in London since 2007. (7 words)

I have lived in London for eight years. (8 words)

I have lived in London since I was nine. (9 words)

I have been living in London since I was ten. (10 words)

I have been living in London for more than eleven years. (11 words)

In pairs, each student throws one dice. Without showing the other their score, they predict the total of the two by saying the sentence with the appropriate number of words. For example, if a student throws five and guesses the other dice is four, they say the nine-word sentence. After both have said their sentences (which must not be the same), they reveal their dice, and the one nearest the total is the winner.

This pen and paper game can be adapted for spelling longer words. Put the students in groups of three, two players and a judge. The judge briefly shows each player a different word with the same number of letters, eg impossible and importance (prepare these beforehand). As in the original game, students take turns in joining dots on a grid. They claim each box they complete, but instead of marking them with their initials, they use a letter from their word, and the first to finish all letters in the correct order wins. A 5x6 dot grid produces 20 boxes, enough for two ten-letter words.

Games are a great motivating factor for many students. If your students have a game they like, why not adapt it for language learning? It is simply a question of matching the game with a suitable language point or skill. With thought, almost any game can be a language game.

Please check the Creative Methodology for the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Methodology and Language for Primary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Methodology and Language for Secondary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching English Through Multiple Intelligences course at Pilgrims website.

|