Teachers’ Feedback on EFL Students’ Writings: A Linguistic or Life Syllabus Perspective

Reza Pishghadam, Reza Zabihi and Momene Ghadiri, Iran

Reza Pishghadam has a Ph.D. in Teaching English as a Foreign Language (TEFL) from Allameh Tabataba’i University in Tehran. He is currently on the English faculty of Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Iran. He is now associate professor of TEFL, who teaches first language theories, sociopsychological aspects of language education, and applied linguistics. Over the last five years, he has published more than one hundred articles and books in different domains of English language education. In 2007, he was selected to become a member of the National Association of Elites of Iran. In 2010, he was classified as the top researcher in humanities by the Ministry of Sciences, Research, and Technology of Iran. His current research interests are: Psychology and Sociology of language education, Cultural studies, Syllabus design, and Language testing; affiliation: Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad, Iran. E-mail: pishghadam@um.ac.ir

Reza Zabihi is a PhD candidate of Applied Linguistics in University of Isfahan, Isfahan, Iran. He is also a member of Iran’s National Elites Foundation (INEF). He also holds an MA degree in Applied Linguistics from Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad, Iran. His major research interests include syllabus design as well as sociolinguistic and psycholinguistic studies. He has published 40 research articles in local and international journals and is currently teaching at University of Isfahan, Iran; affiliation: Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad, Iran. E-mail: zabihi@hotmail.com

Momene Ghadiri is a PhD candidate of TEFL at the University of Isfahan, Isfahan, Iran. Her main areas of research are English teaching, discourse analysis, and sociolinguistics. She holds an MA degree in TEFL; affiliation: Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad, Iran

E-mail: momene.ghadiri@gmail.com

Menu

Abstract

Introduction

Theoretical background

Method

Data sources

1. Written feedback

2. Classroom observation

Results

1. Document analysis of written feedback

2. Analysis of observation data

Discussion

References

Appendix

In this study we adopt a mixed methods approach to examining the extent to which ELT (English as a Foreign Language) university professors integrate relevant life skills into the L2 writing curriculum, particularly through the feedback that they normally provide learners with. The first phase of the study involved the collection of quantitative data to examine the nature of second language (L2) writing teachers’ linguistic-bound or life-responsive feedback. To this end, analysis of the number and types of feedback provided by L2 writing teachers on written compositions (N = 300) was conducted. Follow-up classroom observations (N = 8) were also carried out. The results from document analyses revealed that around 70% of all the feedback covered grammatical issues and mechanics of writing, while paying little, if any, direct attention to the enhancement of learners’ life skills. Besides, the follow-up qualitative phase (classroom observations) added more plausibility to the results obtained from document analyses of written feedback. There were found rare cases where the critical and creative thinking abilities of language learners were highlighted, but these were argued to be triggered in an indirect, limited, and sporadic fashion. In the end, the theoretical and practical implications of this study were discussed.

It goes without saying that youngsters are the most resourceful and dynamic members of the society, by virtue of their substantive physical and intellectual endowments. Lamentably, however, one has to acknowledge the fact that a great majority of our younger generation is incapable of utilizing its full potential in a socially desirable manner due to the absence of proper instruction and motivation. Therefore, learning life skills is a fruitful practice that helps individuals to deal effectively with everyday challenges of life; accordingly, life skills training can enable individuals to behave in pro-social ways and help them take more responsibility for their behaviors and actions.

In effect, school can be an appropriate place for introducing life skills programs alongside other academic subjects (Matheson & Grosvenor, 1999). Therefore, given the fact that schools enjoy a high credibility with students’ parents and community members (WHO, 1997), they can be sites for a ‘life skills intervention’ (Behura, 2012). In this view, life skills are defined by the Mental Health Promotion and Policy (MHP) team in the World Health Organization (WHO) as “the abilities for adaptive and positive behavior that enable individuals to deal effectively with the demands and challenges of everyday life” (WHO, 1999). The pivotal life skills emphasized by the WHO include psychosocial and interpersonal competencies such as, decision making, problem solving, creative thinking, critical thinking, effective communication, interpersonal relationship skills, self-awareness, empathy and understanding, coping with emotions and coping with stress.

It is widely acknowledged that the enhancement of these skills should be seriously taken into account in the context of education (Brooks, 2001; Francis, 2007; Goody, 2001; Larson & Cook, 1985; Matthews, 2006; Noddings, 2003; Radja, Hoffmann, & Bakhshi, 2008; Spence, 2003; Walker, 1999). Nowadays in many parts of the world, life skills training form a crucial and regular section of the school curriculum. As a value-addition program, life skills education aims at helping individuals understand their own real self, adjust socially and emotionally, and become enabled to evaluate their abilities and potentials (Francis, 2007). Further, life skills education guides students in the enhancement of their decision making skill as well as their abilities to construct positive values and self-concept and, in so doing, promote and modify their contributions to the society (Spence, 2003).

Over the past thirty years or so, the attitudes towards literacy have been fading away from literacy for its own sake to its potentiality to be used in real life (Oxenham et al., 2002). As Singh (2003) has pointed out, an essential hallmark of literacy education should comprise the activities which aim at enhancing life skills rather than being designed primarily as a precondition of programs. More specifically, within the communicative paradigm of language teaching, the writing skill is admired for its unique stature. It is through writing that individuals can convey a variety of messages to different readers. Yet it seems that the writing process imposes great demands on the learners, making this skill difficult to be mastered. To enhance the skill of writing, teachers generally work on the vocabulary, grammar, fluency and the mechanics of writing. However, no doubt that “writing is a human activity which reaches into all other areas of human endeavor—expansive in a way that casts doubt on conventional boundaries between individual and society, language and action, the cognitive and the social” (Atkinson, 2003, p. 10).

Having referred to the current status of the field of L2 writing as the “post-process” era, Atkinson (2003) seeks to give prominence to the complex nature of L2 writing and call for training teachers and researchers who can transcend the traditional outlooks on the teaching of L2 writing which normally foreground issues such as mechanics of writing, drafting, peer review, editing, grammar, vocabulary, etc. and, instead, take into consideration the multifarious connections that can be made between L2 writing and the intellectual, political and sociocognitive issues. By and large, it thus seems that merely mastering the subskills of writing cannot guarantee the success in effective writing (Olshtain, 2001). Apparently, more is needed to be successful in this skill. Straightforward though this characterization may seem, it raises the thorny issue of whether language teachers showcase response, resistance, or restraint to move beyond the teaching of writing subskills.

In most recent years, the notion of ‘life syllabus’ has been introduced based on which language teachers are recommended to give more priority to life issues in English Language Teaching (ELT) classes (Pishghadam, 2011; Pishghadam & Zabihi, 2012; Pishghadam, Zabihi, & Kermanshahi, 2012). Accordingly, it has been argued that life should be given more primacy than language in class. It implies that language syllabus must be planned based on the principles of life syllabus. This is not at all to suggest that language learning should be ignored in ELT contexts; it is merely to show that language learning should not be considered the end product of a language class. Rather, primacy ought to be given to the improvement of learners’ life qualities through the development and application of life syllabuses in ELT classes. Recently, the extension of the aims of ELT syllabus design to include non-linguistic objectives in the syllabus has been an important shift of focus in English language teaching in the sense that practitioners of the field no longer have to merely enhance learners’ language-related skills and knowledge (Richards, 2001). Alternately, they are more or less responsible for advancing learners’ whole-person growth, including not only their intellectual development but also their learning strategies, confidence, motivation, and interest.

Under this account, it reasonably seems that L2 teacher feedback has an important role to play in the promotion of learners’ life qualities. As Freire (1998) puts it, sometimes even a simple gesture on the part of a teacher, be it a significant one or not, may have an abysmal effect on a student’s life. Further, previous studies on students’ views about error feedback (Chandler, 2003; Ferris, 1995; Gram, 2005; Hedgcock & Lefkowitz, 1994; Hyland, 2003; Komura, 1999; Lee, 2005; Leki, 1991; Roberts, 1999) have generally demonstrated that L2 learners highly value teacher feedback on their writings. Therefore, by virtue of the unique features that most of the ELT classes enjoy (Pishghadam, 2011) and based on the ‘post-process’ view of L2 writing which considers L2 writing as a manifold activity that comprises an assembly of sociocognitive, cultural, and ideological issues (Atkinson, 2003), English language teachers should try to foreground life issues in writing classes. Therefore, in this study we take a mixed methods approach to examining the extent to which EFL university professors integrate relevant life skills into the writing curriculum, particularly through the feedback that they normally provide learners with.

On its first appearance in the 1950s, applied linguistics was considered synonymous with language teaching (Strevens, 1992) which, over time, is currently being studied as a division of applied linguistics, and is highly open to receive ideas from several branches of applied linguistics such as sociolinguistics and psycholinguistics. These areas have shed some light on English language learning and teaching to help ELT practitioners enrich their understanding of the field. These ideas are in the form of prescriptions which are supposed to enhance and enrich the field of English language teaching and learning, but virtually, it is argued, make English teachers nothing but consumers of the findings of other disciplines (Schmitt, 2002).

Considering that any discipline has two complementary parts of theoretical and applied, it seems to us that, in the case of the field of ELT, the applied part has been ignored. According to Pishghadam’s (2011) proposal, language teachers should no longer be consumers of the findings of other disciplines but should rather take on a more contributory and life-changing status. The idea was further developed by Pishghadam and Zabihi (2012) with the aim of introducing a new type of syllabus, i.e. life syllabus, to ELT professionals and encouraging the ELT community to consider the promotion of learners’ life qualities prior to language learning.

Given this apparent significance, the question of whether language teachers consider life issues, and to what extent, should be investigated extensively. The significance of the present study thus lies in examining one application of the theory of applied ELT to English language classes, giving the theory more empirical adequacy. Granted that the writing ability, more than any other skill, imposes great demands on the learners, making this skill difficult to be mastered, we believe that language teachers should make attempts at enhancing learners’ life qualities in writing classes rather than merely working on the vocabulary, grammar, fluency and the mechanics of writing.

In this manner, for instance, DasGupta and Charon (2004) have suggested reflective writing exercises to be integrated into the medical curriculum in order to enhance the empathy of medical students. Moreover, Deane (2009) advocates the use of such reflective practices in writing for the purpose of enhancing students’ self-belief and confidence. More specifically in the L2 context, others have also made attempts at shifting the focus of inquiry in L2 teaching to creative writing practices (e.g., Rojas-Drummond, Albarran, & Littleton, 2008; Vass, 2004) as well as those which can enhance learners’ critical thinking abilities in writing classes (cf. Mok, 2009), considering the facts that there is a close link between learners’ thinking skills and writing development and that these skills play significant roles in one’s success in life (Tharp & Gallimore, 1988). In another vein of argument, Kubota (1999) portrays the links that should essentially be made between L2 writing and issues of power, race, social class, and gender. For the purposes of characterizing L2 writing, Atkinson (2003), inspired by Trimbur’s (1994) notion of “post process”, refers to the process of L2 writing as a manifold activity that comprises an assembly of sociocognitive, cultural, and ideological issues:

Writing is a human activity which reaches into all other areas of human endeavor—expansive in a way that casts doubt on conventional boundaries between individual and society, language and action, the cognitive and the social. I therefore view the notion of “post-process” as an appropriate basis on which to investigate the complex activity of L2 writing in its full range of sociocognitive situatedness, dynamism, diversity, and implications (p. 10).

Firstly, the origin of the social situatedness of L2 writing can be traced back to Swales’ (1990) concepts of genre and discourse community as well as Johns’ (1990) discussions of social constructionism which can additionally be brought to bear on what Atkinson (2003) hopes to consider as one part of the ‘post-process’ view of L2 writing. In much the same way, the ideological outlook on L2 writing (Atkinson, 2003) has been developed on the grounds that reading and writing are not only related to individual and cognitive aspects but also directly enmeshed with relations of power as well as with societal and cultural issues (e.g., Belcher, 2001; Bourdieu, 1977; Pennycook, 1996; Vandrick, 1995). Moreover, L2 writing can be regarded as a cultural activity (Atkinson, 2003) where issues such as the domination of western social institutions as well as the influence of culture on learners’ L2 writings can be discussed extensively (e.g., Kubota, 1999; Spack, 1997).

In this connection, there is no doubt that feedback plays a central role in developing writing proficiency among second language learners (Miao, Badger, & Zhen, 2006); this feedback is provided to ask for further information, to give directions, suggestions, or requests for revision, to give students new information that will help them revise, and to give positive feedback about what the students have done well (Ferris, 1997). Besides, studies on teacher feedback (e.g., Chandler, 2003; Ferris, 1995; Gram, 2005; Hedgcock & Lefkowitz, 1994; Hyland, 2003; Komura, 1999; Lee, 2005; Leki, 1991; Roberts, 1999) have generally confirmed that L2 learners highly value teacher feedback on their writings.

Seen through a different lens, writing teachers provide spoken and written feedback not only to support learners’ writing development but also to improve their confidence as writers. In effect, as Lee (2009, p. 131) has pointed out, “writing is a personal process where motivation and self-confidence of the students as writers may expand or contract depending on the type of comments incorporated in the feedback.” For instance, in addition to the favorable impacts that peer feedback has on the writing quality, it has also proved beneficial in enhancing learners’ critical thinking abilities, autonomy and social interaction (Yang, Badger, & Yu, 2006). Therefore, granted that one of the techniques through which life skills can be imparted is to provide appropriate feedback to individuals, it is important, along the lines of applied ELT (Pishghadam, 2011), to check out the extent to which teachers’ feedback on learners’ writings incorporates learners’ life issues. Therefore, in this study we attempt to examine whether EFL university professors provide learners more with linguistic skills or life issues. The following research questions were addressed in this study:

- What are the characteristics of teachers’ feedback on learners’ writings?

- To what extent do language teachers try to enhance learners’ life qualities in writing classes?

In this study, a triangulation of document analyses and classroom observations was used in order to enhance the validity of inferences made (Johnson, Onwuegbuzie, & Turner, 2007).

A total number of three-hundred essay compositions, provided with feedback, were subject to investigation. Two raters were asked to rate the documents based on the scoring sheet provided for them. The scoring system was based on seven categories of mechanics (punctuation, spelling, capitalization, face, paragraphing, handwriting, space), grammar (tense, sentence structure, structure complexity, phrasal structure, number, agreement, article, preposition, pronoun, etc.), organization (paragraph development, paragraph structure, essay development, essay structure), style (tone, mode, register, formality, awkward structure, appropriateness of use), unity (relevance of sentences to the topic, relevance of sentences to each other, transitions), vocabulary (word usage, word choice, use of different and complex vocabulary), and content (development of idea, quality of idea).

In addition, four categories of life-responsive language teaching, i.e. life-wise empowerment (the language teacher’s ability to support mental well-being and behavioral preparedness of learners including creative and critical thinking), adaptability enhancement (the language teacher’s ability to foster adaptive and positive behaviors that enable individuals to deal effectively with the demands and challenges of everyday life including problem-solving and decision making), pro-social development (the language teacher’s ability to promote personal and social development including interpersonal bonds and effective communication), and life-over-language preference (the language teacher’s ability to center attention on learners’ qualities of life including their feelings and emotions in comparison with linguistic points) were also taken into account. In this connection, Pishghadam, Zabihi and Ghadiri (2012) developed and validated a scale for the measurement of life-responsive language teaching beliefs through Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), coming up the aforementioned subscales. The internal consistency of the scale was also found to be .94, indicating high reliability. Accordingly, appropriate descriptive statistical procedures were followed to interpret the results of the document analyses quantitatively and determine the significant differences between the life-wise and linguistic-bound feedback provided.

In order to shed more light on the issue, the data collection procedure was followed by 12 hours observation of EFL writing courses at three universities in the province of Isfahan. Eight 90-minute academic writing classes were observed. The researchers tried to pay careful heed to teachers’ practices inside the class. Consequently, the feedback provided for the students were analyzed in terms of linguistic-bound or life-wise pointer. The data pertaining to classroom observations were analyzed and interpreted qualitatively to examine the degree to which the feedback provided by EFL writing teachers concerned life-wise or linguistic-bound issues. The data were subsequently analyzed in terms of the eleven categories cited above. The detailed information on the observed classes is shown in Table 1.

Table 1

Characteristics of the Observed L2 Writing Classes

| Class | Course Title | Time | Duration | Teacher Experience |

| A | Essay Writing | Wednesday (8-10 AM) | 90 min | 6 years |

| B | Paragraph Development | Monday (8-10 AM) | 90 min | 8 years |

| C | Paragraph Development | Monday (8-10 AM) | 90 min | 13 years |

| D | Essay Writing | Tuesday (10-12 AM) | 90 min | 5 years |

| E | Essay Writing | Saturday (4-6 PM) | 90 min | 12 years |

| F | Essay Writing | Monday (8-10 AM) | 90 min | 10 years |

| G | Essay Writing | Saturday (8-10 AM) | 90 min | 15 years |

| H | Essay Writing | Monday (10-12 AM) | 90 min | 8 years |

Finally, the data obtained from three-hundred essay compositions, provided with feedback, were analyzed. Two raters were asked to rate the documents based on the scoring sheet provided for them. The inter-rater reliability between the raters was obtained to be 80%, indicating high reliability. Accordingly, descriptive statistics were utilized to interpret the results of the document analyses quantitatively and determine the significant differences between the life-wise and linguistic-bound feedback provided. As it is shown is Table 2, a total number of 3516 feedbacks were provided on the 300 compositions under investigation. Among these, grammar (N= 1386) and mechanics (N= 1065) enjoy the highest frequency. That is, around 70% of all the written feedbacks revolved around grammatical issues and mechanics of writing.

Table 2

Type, Number, and Percentage of Linguistic-bound and Life-responsive Written Feedback

| No. | Type of Feedback | Number of Feedbacks | Percent |

| 1 | Mechanics | 1065 | 30.29 |

| 2 | Grammar | 1386 | 39.41 |

| 3 | Organization | 171 | 4.86 |

| 4 | Style | 108 | 3.07 |

| 5 | Unity | 69 | 1.96 |

| 6 | Vocabulary | 414 | 11.77 |

| 7 | Content | 278 | 7.90 |

| 8 | Pro-social Development | 5 | 0.14 |

| 9 | Life-wise Empowerment | 11 | 0.31 |

| 11 | Life-over-language Preference | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | Adaptability Enhancement | 9 | 0.25 |

| Total | 3516 | 100 |

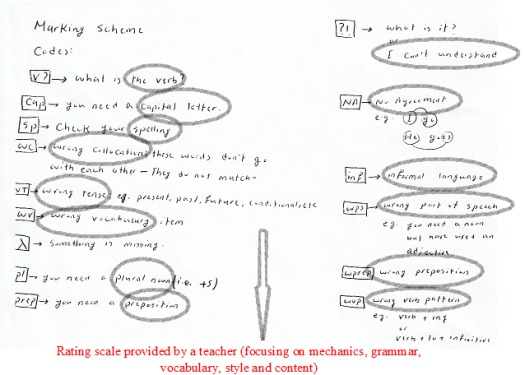

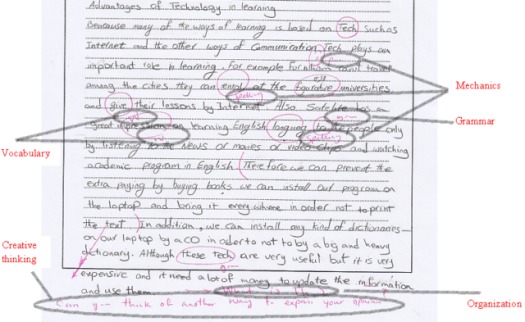

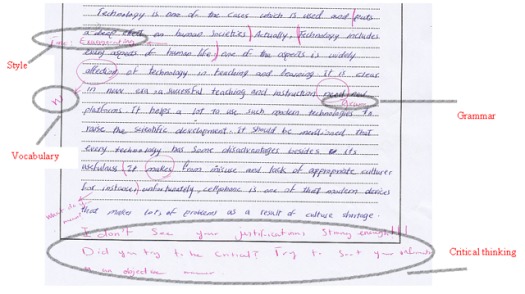

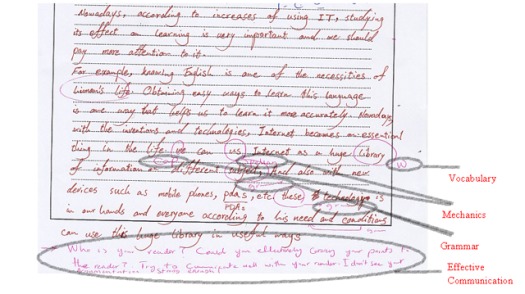

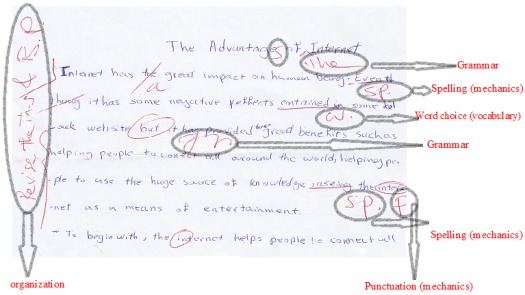

In order to better illustrate the types of feedback given, the readers are provided with some examples, as can be seen in the sample extracts below. The first extract clearly sketches the conventional categories of feedback provided such as grammar, vocabulary, mechanics (spelling, punctuation), and organization (see Appendix). In much the same way, the second extract (see Appendix) depicts part of an essay being provided with feedback including those pertaining to grammar, organization, vocabulary, and content (development of idea, quality of idea). To put the results on a more concrete footing, below we refer to a rating scale provided by an L2 writing teacher, all centering on linguistic-bound issues such as mechanics of writing, grammar, organization, vocabulary, style and content.

Sadly, however, the underlying factors of life-responsive language teaching did not receive well-deserved attention. Nonetheless, some instances of life-responsive feedback were occasionally observed, as might best be seen in the following extracts, though these can be argued to be indirectly triggering learners’ life skills. As can be seen, in these extracts, the teacher’s feedback not only revolves around issues such as grammar, vocabulary, organization and mechanics of writing, but it also triggers learners’ creative thinking (can you think of another way to express your opinion?), critical thinking (I don’t see your justification strong enough; Did you try to be critical? Try to send your information in an objective manner), and effective communication with the reader (Who is your reader? Can you effectively communicate and convey your points to the reader? Try to communicate well with your reader) as well.

Our observations of the eight L2 academic writing classes revealed that the majority of classes in our sample revolved around issues such as grammar, organization, style (formality, tone), vocabulary, mechanics, unity, and content. The classes started with an introduction and exemplification by the teacher of a particular type of essay followed by the investigation of one or two compositions written by the learners.

For example, Class A started with the teacher’s explanation of sense verbs, modals and their past and passive structures. The teacher then followed to one of the students’ essays. While providing (teacher/peer) feedback for the student, a hot discussion arose. Along with the students, the teacher tried to challenge the organization of the essay, as well as several structures, word choices, and development of ideas. Apparently, most feedbacks revolved around grammar, organization, style (formality, tone), vocabulary, mechanics, unity and content. Similarly, Class B, essentially a paragraph development course, started with learners’ writings; the teacher provided feedback, mostly on grammar, vocabulary and mechanics. She also suggested a number of formulaic expressions, verbs and conjunctions that learners could use in their writings. It was followed by samples of expository and narrative paragraphs; the teacher provided examples of each paragraph and how to organize them (e.g., different Adj/Adv/N phrases that they could use in order to write narration or exposition). Perhaps these are best summed up in the following interaction between the teacher and one of the students:

Student: Bring a pot of water and boil water. Chopping of onions, green peppers, and mushrooms, and after that …

Teacher: Okay! Wait, wait. You said chopping, yes? Chopping what?

Student: Of onions…

Teacher: Okay. What kind of structure is that? Look here! What kind of structure is this?

Student: Participle

Teacher: Participles are used when you have more than one clause. But you stopped before chopping and changed to another sentence. You cannot have participle from only one clause.

Student: The chop of onions and etc.

Teacher: You can easily say chop the onions; remember, first of all, that of should be omitted. Then you need a determiner the onions, because you mentioned onions in your ingredients.

Class C was a paragraph writing course. It started with students’ writings. Most types of feedback provided dealt with unity, vocabulary, content, and organization. The teacher focused on topic sentence (topic and controlling idea) and supporting sentences. They had some examples concerning the layout of expository paragraph and the teacher, together with the students, tried to provide some examples regarding how to organize these paragraphs. They eventually referred to the book and did some exercises regarding the organization of such paragraphs. The following interaction illustrates a type of feedback pertaining to word usage:

Student: I think the affection of music in my life is more than listening to a music and say wow, what an amazing song it is!

Teacher: why affection? Read your sentence once more.

Student: I think the affection of music in my life…

Teacher: Why affection? The effect of music…; affection is closest in meaning to emotions and feelings…

Class D started with teacher’s explanation of mechanism essay as opposed to instructional essay, and then proceeded to categorization essay. Thus, most of the time of the class was devoted to organization of three types of essay. It was followed by analyzing one of the students’ writings. Again, comments were centered on mechanics, grammar, vocabulary, and content. The focus of Class E was mostly on the structure of a concluding paragraph: (a) restated thesis and (b) clincher. The teacher provided a number of examples and the students also read out loud their own paragraphs. In much the same way, Class F was devoted to organization. They were working on classification essay. The teacher started with a brief introduction of classification essay. They went through the book, reading some examples and doing some exercises. They mostly worked on thesis sentence, blueprint and motivator, clincher, and rewording thesis sentence. Some feedbacks which have been provided dealt with vocabulary and style (formality). Also, the teacher emphasized the role of mechanics (margin, punctuation, and handwriting), and grammar.

In addition, in Class G, essay organization, grammar, vocabulary, and in some parts mechanics, style and unity, were highlighted. The class started with a short review of the types of essays they have had so far. It proceeded to one of the essays written by one of the students. Along with the students, the teacher provided feedback which centrally dealt with mechanics, organization, style, vocabulary, grammar, unity and content. Below is an example of the feedback provided by the teacher, highlighting the style and tone of the writer:

Look at the sentence: “They found that the first group had more unbalanced treatment because they have been kept in a public place with different manners”. The Verb found should be substituted with another one like showed. I told you before that in academic writing no one talks with certainty. Your verbs should be like might, may, and etc. You should communicate your ideas smoothly to your readers not with absolute certainty. You should make use of verbs like ‘sound’, ‘seem’, ‘show’ instead of ‘was’. It was… means that I did the experiment, I observed something and there was nothing wrong with my experimentation. But in academic writing, we say that our study may have had limitations as well. Therefore, from now on, try to teach yourself not to talk with absolute certainty in academic writing.

Finally, Class H was centered on mechanics, organization and unity. They went through the book, looking at some examples of compare and contrast. The teacher then explained coordinating conjunctions and transitions, transitional expressions between sentences, conjunctions which show contrast, essential chunks that they learners memorize and use them in their writings, and punctuations such as comma, colon, semicolon, and dash.

Occasionally, the teachers asked questions which could stir critical thinking of the learners; In Class A, for instance, the teacher frequently asked questions such as the following:

Has she succeeded in conveying the point she was going to communicate? Is this structure needed? Is it limited to our people? Or is it an international phenomenon? I believe that foreign countries misuse or even abuse much more frequently than we do, don’t they? Be biased or not? Is it possible to reduce subjectivity and change the tone?

In some other instances, teachers challenged the ideas regarding the content of the compositions and, having sought peer correction, allowed learners to address their own problems independently; In Class F, the instructor involved the learners in deciding about thesis statement and blueprints and whether they are appropriate or not; this way the students had to resort to critical thinking and had to use their creativity to rewrite them, though these might be argued to be merely indirect tapping of these thinking skills. In Class D, the teacher highlighted the importance of mechanism essays as they are so close to real life in that learners can write about how everything in their life works and functions. Furthermore, in Class G, the teacher tried to challenge the idea developed by the writer:

Writer: Kindergartens, as the most similar places to home, change to the most current places to look after the kids.”

Teacher: They are! Why change to?

Writer: Somebody launched a research to compare two groups of kids, one was keeping in the kindergarten and second one not.

Teacher: where was the second? At home? His uncle’s house? His aunt’s?

Writer: At last, despite some useful effects of kindergartens, mostly these places cannot be as secure as homes.

Teacher: it is as plain as day! Kindergartens are not as secure as home. If you have not written this essay and those have not done that research, the result is clear enough that the Kindergartens are not as secure as home!

The same teacher reminds the learners of the prevalence of unpreventable bias in everyday life.

Teacher: But what about us? We don’t use them the way they are supposed to be?

Student: I think she wanted to say what about our country and start to until the part in this development … the writing is a little biased.

Teacher: I agree that this is a bit long; but people are biased. All of us are biased. We are biased. There is no remedy to this problem. I don’t know why some people say that we shouldn’t be biased; but they never tell you how!

A mixed methods design was adopted in the present study given that mixed methods research approaches are generally supposed to give us a more comprehensive understanding of complex phenomena (Greene, Benjamin, & Goodyear, 2001) and can produce “the most informative, complete, balanced, and useful research results” (Johnson, Onwuegbuzie, & Turner, 2007, p. 129). Upon doing so, we needed not choose between either quantitative or qualitative research traditions (Tashakkori & Teddlie, 2003) but instead, we opted for the integration of both traditions into one which can yield more comprehensive, reliable and valid outcomes (Dornyei, 2007).

As illustrated in our analyses of written feedback, more than two thirds of the feedbacks were centered on grammatical issues and mechanics of writing, displaying the wholesale ignorance of potential life-responsive feedback. Equivalently, this does indeed appear to be the case while interpreting classroom observations. In much the same way, additional evidence relating to the lack, if not the absence, of life-responsive feedback comes from the observation made by the researchers of eight L2 academic writing classes. The results revealed that the majority of classes in our sample revolved around issues such as grammar, organization, style (formality, tone), vocabulary, mechanics, unity, and content. Such results can additionally be brought to bear on what we hope to show is the presumed lack of life-wise language teaching. In other words, results from classroom observations lent added plausibility to the results of document analyses of written feedback.

Be that as it may, on the basis of the data discussed so far, the question as to whether or not EFL writing teachers’ feedback incorporates life issues cannot receive a straightforward answer. For, on the one hand, the classroom observations and document analyses of written feedback indicated that the L2 academic writing classes in Iran are often preoccupied with conventional categories, sometimes pointing to the wholesale ignorance of Atkinson’s (2003) notion of ‘post-process’ which considers L2 writing as a manifold activity that comprises an assembly of sociocognitive, cultural, and ideological issues. Obviously, there was no systematic emphasis on the enhancement of life skills. On the other hand, there were rare cases where the critical thinking and creative thinking skills of language learners were taken into consideration, though in an indirect, limited, and sporadic manner.

Hence, one way of countering this bitter truth is to suppose that some life skills such as critical thinking and creative thinking were sometimes highlighted, though in an indirect and sporadic fashion. The writers do not aim to ignore the role of, say, critical and creative thinking which are essential in life-skill training inside L2 writing classes. Writing class, as its name suggests, is inherently creative and critical. Otherwise, students cannot develop their ideas within the border of their essay compositions.

Under this account, the writers do acknowledge that they could trace feedback on critical and creative thinking indirectly in terms of challenging content, vocabulary, organization and style (a number of questions have been referred to). However, as applied ELT (Pishghadam, 2011) suggests, these skills should be directly dealt with inside the class. In some cases, by choosing an appropriate topic, the teacher can directly foster critical and creative thinking through composition essays. Put another way, we do not intend to ignore the role of mechanics, grammar, etc. in writing; rather, we believe that sometimes language teachers get immersed in conventional categories at the cost of several essential life skills.

These findings obtained from a triangulation of data collection, analysis, and interpretation lends great support to Pishghadam and Zabihi’s (2012) claim that life issues have sadly been ignored in the field of English language teaching. When it comes to L2 writing classes, due to the importance of the sociocultural and interactional situatedness of writing (Matsuda, 2003) as well as the ideological considerations present in L2 writing contexts (Atkinson, 2003), the professionals in the fields of materials development and syllabus design should pay careful attention to the direct incorporation of these non-linguistic issues into the L2 writing curriculum, rather than relying solely on the teachers’ capability to occasionally and unsystematically give prominence to them. Moreover, in order to have an effective implementation of life skills education in L2 writing classes, there would be a need and cause for a comprehensive teacher-training program in life skills education for the purpose of training educational language teachers who are not only experts in the L2 writing system but also have a fair knowledge of other disciplines as well (Pishghadam, Zabihi, & Kermanshahi, 2012).

In sum, although in the present study we could come to a sort of convergence between the results obtained via analysis of written feedback and classroom observations, pointing to the fact that the feedback provided by Iranian L2 writing teachers, at least in the academic setting, is mostly centered on conventional linguistic-bound (rather than life-responsive) categories, it should be pointed out that the results of this study must be interpreted within certain limitations and reservations. First, classroom observations were limited in number and duration in that only eight L2 academic writing classes (one session from each class) were observed in three universities. Second, for classroom observations, convenience sampling was conducted where the teachers whose classes were to be observed had control over whether to participate, leaving the potentiality for a self-selection bias; observation of other classes might have yielded different results. Third, the researchers limited themselves to observing the L2 writing classes only, disregarding the fact that other courses (i.e. listening/speaking and reading classes) might also offer equally good opportunities for a life-skills intervention. Hence, obviously, much work is still needed to understand the complex algorithms which map life issues to language, but in the meantime, methodologically speaking, we need to seek evidence for other areas of language education as well.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the project reported here was supported by a grant-in-aid of research from Ferdowsi University of Mashhad in 2013 (contract code: 21524) without which this research would not have been possible.

Atkinson, D. (2003). L2 writing in the post-process era: Introduction. Journal of Second Language Writing, 12, 3-15.

Behura, S. (2012). A review on life skills education in schools. Elixir Psychology, 43, 6790-6794.

Belcher, D. (2001). Does L2 writing have gender? In T. Silva & P. Matsuda (Eds.), On second language writing (pp. 59-72). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Bourdieu, P. (1977). The economics of linguistic exchanges. Social Science Information, 16, 645-668.

Brooks, R. (2001). Fostering motivation, hope, and resilience in children with learning disorders. Annals of Dyslexia, 51, 9-20.

Chandler, J. (2003). The efficacy of various kinds of error feedback for improvement in the accuracy and fluency of L2 student writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 12(2), 267-296.

DasGupta, S., & Charon, R. (2004). Personal illness narratives: Using reflective writing to teach empathy. Academic Medicine, 79(4), 351-356.

Deane, M. (2009). Reflective writing pedagogy. In H. Bulpitt & M. Deane (Eds.), Connecting reflective learning, teaching and assessment (pp. 43-48). London: Higher Education Academy.

Dornyei, Z., (2007). Research methods in applied linguistics: Quantitative, qualitative and mixed methodologies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ferris, D. R. (1995). Student reactions to teacher response in multiple-draft composition classrooms. TESOL Quarterly, 29, 33-53.

Francis, M. (2007). Life skills education. www.changingminds.org.

Freire, P. (1998). Pedagogy of freedom: Ethics, democracy, and civic courage. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Goody, J. (2001). Competencies and education: Contextual diversity. In: D. S. Rychen, & L.H. Salganik (Eds.), Defining and selecting key competencies. Gottingen, Hogrefe and Huber Publications.

Gram, G. (2005). The effect of teachers’ written feedback on ESL students’ perception: A study in a Saudi ESL university-level context. Annual Review of Education, Communication and Language Sciences, 2. [Online] Available:

http://research.ncl.ac.uk/ARECLS/vol2_documents/Grami/grami.htm

Greene, J. C., Benjamin, L., & Goodyear, L. (2001). The merits of mixing methods in evaluation. Evaluation, 7(1), 25-44.

Hedgcock, J., & Lefkowitz, N. (1994). Feedback on feedback: Assessing learner receptivity in second language writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 3, 141-163.

Hyland, F. (2003). Focusing on form: Student engagement with teacher feedback. System, 31, 217-230.

Johns, A. M. (1990). L1 composition theories: Implications for developing theories of L2 composition. In B. Kroll (Ed.), Second language writing: Research insights for the classroom (pp. 24-36). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Johnson, R. B., Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Turner, L. A. (2007). Toward a definition of mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(2), 112-133.

Komura, K. (1999). Student response to error correction in ESL classrooms. Unpublished master’s thesis, California State University, Sacramento.

Kubota, R. (1999). Japanese culture constructed by discourses: Implications for applied linguistics research and ELT. TESOL Quarterly, 33, 9-35.

Larson, D. G., & Cook, R. E. (1985). Life-skills training in education. Journal of Group Psychotherapy, Psychodrama, & Sociometry, 38(1), 11-22.

Lee, I. (2005). Error correction in the L2 writing classroom: What do students think? TESL Canada Journal, 22(2), 1-16.

Lee, N. S. C. (2009). Written peer feedback by EFL students: Praise, criticism and suggestion. Komaba Journal of English Education, 129-139.

Leki, I. (1991). The preferences of ESL students for error correction in college level writing classes. Foreign Language Annals, 24(3), 203-18.

Matheson, D., & Grosvenor, I. (Eds.) (1999). An Introduction to the study of education. London: David Fulton Publisher.

Matsuda, P. (2003). Process and post-process: A discursive history. Journal of Second Language Writing, 12, 65-83.

Matthews, B. (2006). Engaging education: Developing emotional literacy, equity, and co-education. McGraw-Hill Education: Open University Press.

Miao, Y., Badger, R., & Zhen, Y. (2006). A comparative study of peer and teacher feedback in a Chinese EFL writing class. Journal of Second Language Writing, 15, 179-200.

Mok, F.Y. (2009). Language, learning and context: developing students' critical thinking in Hong Kong secondary school English writing classes. The 42nd Annual Meeting of the British Association for Applied Linguistics (BAAL), Newcastle University, U.K., 3-5 September 2009.

Noddings, N. (2003). Happiness and education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Olshtain, E. (2001). Functional tasks for mastering the mechanics of writing and going just beyond. In Celce-Murcia (Ed), Teaching English as a second or foreign language (pp.207-217). Boston: Heinle & Heinle.

Oxenham, J., Diallo, A. H., Katahoire, A. R., Petkova-Mwangi, A., & Sall, O. (2002). Skills and literacy training for better livelihoods: A review of approaches and experiences. Washington D.C., World Bank Africa Region Human Development Series.

Pennycook, A. (1996). Borrowing others’ words: Text, ownership, memory, and plagiarism. TESOL Quarterly, 30, 201-230.

Pishghadam, R. (2011). Introducing Applied ELT as a new approach in second/foreign language studies. Iranian EFL Journal, 7 (2), 9-20.

Pishghadam, R., & Zabihi, R. (2012). Life syllabus: A new research agenda in English language teaching. TESOL Arabia Perspectives, 19(1), 23-27.

Pishghadam, R., Zabihi, R., & Ghadiri, M. (2012). Design and construct validation of a life-responsive language teaching beliefs questionnaire for L2 teachers. Proceedings of LLT-IA Conference, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Iran.

Pishghadam, R., Zabihi, R., & Kermanshahi, P. (2012). Educational language teaching: A new movement beyond reflective/critical teacher. Life Science Journal, 9(1), 892-899.

Radja, K., Hoffmann, A. M., & Bakhshi, P. (2008). Education and capabilities approach: Life skills education as a bridge to human capabilities.

http://ethique.perso.neuf.fr/Hoffmann_Radja_Bakhshi.pdf

Richards, J. (2001). Curriculum development in language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Roberts, B. J. (1999). Can error logs raise more than consciousness? The effects of error logs and grammar feedback on ESL students’ final drafts. Unpublished master’s thesis, California State University, Sacramento.

Rojas-Drummond, S.M., Albarran, C.D., & Littleton, K.S. (2008).Collaboration, creativity and the co-construction of oral and written texts, Thinking Skills and Creativity, 3, 177-191. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2008.09.008

Schmitt, N. (2002). An introduction to applied linguistics. London: Arnold.

Singh, M. (2003). Understanding life skills. Background paper prepared for the Education for All Global Monitoring Report 2003/4. Gender and Education for All: The Leap to Equality.

Spack, R. (1997). The acquisition of academic literacy in a second language: A longitudinal case study. Written Communication, 14, 3-62.

Spence, S.H. (2003). Social skills training with children and young people: Theory, evidence and practice. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 8(2), 84-96.

Strevens, P. (1992). Applied linguistics: An overview. In W. Grabe & R. B. Kaplan (eds.), Introduction to applied linguistics. (pp. 13-31). Addison-Weley Publishing Company.

Swales, J. M. (1990). Genre analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tashakkori, A., & Teddlie, C. (Eds.). (2003). Handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Tharp, R. G., & Gallimore, R. (1988). Rousing minds to life: Teaching, learning and schooling in social context. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

Trimbur, J. (1994). Taking the social turn: Teaching writing post-process. College Composition and Communication, 45, 108-118.

Vandrick, S. (1995). Privileged ESL university students. TESOL Quarterly, 29, 375-380.

Vass, E. (2004). Understanding collaborative creativity: Young children’s classroom-based shared creative writing. In D. Miell & K. Littleton (Eds.), Collaborative creativity (pp. 79-95). London: Free Association Books.

Walker, J. C. (1999). Self-determination as an educational aim. In R. Marples (Ed.), The aims of education. London: Routledge.

World Health Organization (WHO). (1997). Life skills education for children and adolescents in schools: Introduction and guidelines to facilitate the development and implementation of life skills programmes. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Programme on Mental Health.

WHO (1999). Partners in life skills education: Conclusions from a United Nations inter-agency meeting. Geneva: Department of Mental Health, Social Change and Mental Health Cluster, WHO.

Yang, M., Badger, R., & Yu, Z. (2006). A comparative study of peer and teacher feedback in a Chinese EFL writing class. Journal of Second Language Writing, 15, 179-200.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

|