Empowerment in the Classroom: Enabling Students to Maintain Motivation

Alice Svendson, Japan

Alice Svendson is a teacher at Soka University and Jumonji University in Tokyo, Japan. She has co-authored a student course book, and is interested in student motivation and EFL curriculum design in Southeast Asia.

E-mail: chester@inter.net

Menu

Introduction

Overview and objectives

Defining terms

Empowerment in motivation models

Maintaining motivation: teacher’s feedback

Students’ feedback on teacher feedback: a small study

The question of too much praise

The need to modify teachers’ classroom feedback/discourse

Suggestions for teachers

Empowering strategies for students

Conclusion

References

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Empowerment! When I mentioned this project to a friend over two years ago she thought I wanted to become a good witch. That in itself was reason enough to explore different perceptions of the term. Since then, the word “empowerment” has become a buzz word among educators, social entrepreneurs, and social workers. At that time, I was considering empowerment not only with students, but in work-based relationships with colleagues as well. Through a process of observation and reflection, I began to personally define what seemed to be the virtues of those who empower others and conversely, the so-called vices of people whose behavior can diminish the energy, confidence, and motivation of others.

It seems that people who empower are generally trained listeners, slow to judge and quick to praise. They exhibit empathy in times of grief or disappointment, but more so, joy at others’ successes. They do not seem to compete so much, but rather graciously give credit to others. They know how and when to step back. Individuals who empower show trust and make few attempts to control others. One colleague shared his view of the epitome of an empowering person. Above all, he said, it’s someone who can make you feel that the idea came from you when really it didn’t, yet somehow through the talking, the person steps back, giving you the feeling of confidence. A recent business article mentions this very strategy, which the interviewee says he uses. Adam Lansing, (2011), CEO of a restaurant chain, in an interview, explains that when he became a boss he didn’t like the idea of people doing things because they feared him. He describes two kinds of power – personal power and positional power. Positional power means “I have power over you because I’m your boss… You should fear me because of who I am.” Personal power is what’s inside of a person. The dishwasher could have more personal power than his supervisor. He goes on to say that a trait of a good leader is to make the other person think they came up with the idea, and to give them credit for it. Lansing says that as a manager, what gives you power is how you treat other people, and how you lead. We can all recall people like this who have influenced us – our teachers, our colleagues, and perhaps our managers and administrators.

On the other hand, there are those whose behavior tends to diminish power in others. They seem to be highly competitive, judgmental, more controlling and threatening. We may react more negatively to such kind of treatment, and consequently, with less achievement.

The results of my ruminations on empowerment and disempowerment have contributed to my own personal and professional development. This paper is a product of those reflections. It details how a small investigation of empowerment led to a classroom research project to determine how the teacher’s classroom feedback/behavior affects students’ ability to maintain motivation (empowerment).

As teachers, we may not always see both the virtues of empowerment and vices of disempowerment in our work at different times. Ways in which we increase our skills to empower students and decrease the behaviors which diminish power and confidence will be discussed in this paper. We will be examining a three-fold view of empowerment through the following three questions: what does empowerment mean, how can we as teachers raise our own awareness, and thus modify our classroom discourse and feedback to empower our students more, and thirdly, what new strategies for empowerment can we teach our students?

A. Empowerment and facilitation

The term empowerment is much less frequent than the term motivation in the literature in general, and in particular in the EFL/ESL field. Bordonaro (1999) talks about empowering students as stakeholders, giving suggestions of how to allow students to participate more actively and thus invest more in their classroom learning. She offers suggestions in categories such as grading, vocabulary, presentations and more. However, there are many more articles and books on motivation. As we read through the SLA (second language acquisition) literature and take, for example, Dornyei, (1999), it is not hard to realize the complexity of the subject.

In discussing empowerment in the classroom, one role that is closely related is that described as facilitator. The teacher’s role as facilitator was discussed by Diane Larsen-Freemon (1998). She summarizes the diverse methodologies available to teachers, as well as the influence of technology in the classroom. She concludes that teachers need to include among their many roles, that of facilitator, along with model, drill conductor, counselor, collaborator, technician, and others. With a fresh look through the lens of classroom practice we can see the role of facilitator as one who empowers.

B. Empowerment and motivation

Empowerment, according to the World Book Dictionary (1978) has a surprisingly simple definition. It states that to empower means to enable, permit. More specifically, pertaining to education, the online glossary, Analytic Quality Glossary from Quality Research International, states that to empower in education refers to the development of knowledge, skills and abilities in the learners to enable them to control and develop their own learning. Empowering students involves student participation in such areas as evaluation of content and organization of programs. “The student does not simply choose which teaching programmes to attend but negotiates a learning experience. With the teacher who acts as facilitator…” The Glossary goes on to say that empowerment “enables students to easily go beyond the narrow confines of the ‘safe’ knowledge base of their academic discipline to applying themselves to whatever they encounter in the post education world.”

This is a tall order to fill, but so is to motivate. A quick search in the above mentioned dictionary for the term motivation takes us to its roots in motivate, and ultimately, motive. Motive is described as “a thought or feeling that makes a person act; moving consideration or reason.” Synonyms for motive were incentives, goals. To make a distinction for our purposes in this paper, we might say that the student’s inner driving force is the motivation, and the enabling, facilitating energy that the teacher provides is empowerment.

How does empowerment fit into the motivational models drawn up by researchers in the field of second language acquisition? Let us look at two models to concretely interpret the empowerment phase. Dornyei (1999), in his comprehensive book on motivation devotes the first chapter to theoretical approaches to understanding motivation. One of the models which Dornyei (p.20) explains is Williams and Burden’s (1997) framework. Dornyei outlines their division between internal (perceived value of activities, self-concept, attitudes) and external factors (the learning environment, the broader context). In this model, empowerment could happen in the domain of external factors, under “significant others” (family, teachers, peers) and “interactions with significant others.”

Dornyei’s own model (p.22) is a process model emphasizing the role of the passage of time in motivation. There is a pre-actional, actional, and post-actional stage. In this model, we might say empowerment occurs in the middle or actional stage where “executive motivation” occurs. In explaining this stage Dornyei states that, “Second, the generated motivation needs to be actively maintained and protected while the particular action lasts. This motivational dimension has been referred to as executive motivation, and it is particularly relevant to learning in classroom settings where students are exposed to a great number of distracting influences … that make it difficult to complete the task.” (p.21) According to Dornyei’s model, executive motivation includes, among other things, quality of the learning experience, sense of autonomy, influence of the learner group, and knowledge of self-regulatory strategies. (p.22) In all of these facets, the teacher is an important factor. Maintaining a positive atmosphere, encouraging peer exchanges and positive feedback, enhancing autonomy, including critical thinking skills, and building confidence in learners are part of empowerment.

Grombczewska (2011), in her article titled, “The relationship between teacher’s feedback and students’ motivation,” describes a study in which she measures the amount of classroom feedback teachers give, differentiating between positive and negative teacher comments, and corrections. The amount of class time spent on positive, negative feedback and corrections is recorded (in seconds and minutes) and measured in percentage of class time. The results are then correlated with data on the students’ motivation. “The results are likely to show to what extent the manner in which the teacher provides students with feedback is correlated with their motivation. The result that is expected is that students’ intrinsic motivation is higher when the teacher provides more positive comments and fewer corrections.” (The verb tense here indicates that the full study had not yet been conducted at the time the article went to press – only a portion had been done.)

Grombczewska defines both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Extrinsic motivation is more an awareness of external rewards (grades, recognition), whereas intrinsic motivation has the reward of psychological satisfaction (pleasure of study, achievement of goals). Grombczewska’s well-focused, neat and clear method inspired me to carry out my own less scientific, and more qualitative research, which is explained in the next section.

Prompted by Grombczewska’s classroom research, as mentioned above, I conducted a small study in three university EFL classes at two different universities in Tokyo. The study looked at teacher feedback from the point of view of empowerment, i.e. enabling students to maintain that motivation. It is looking at the “significant others” in Williams and Burden’s model, and the “executive motivation” dimension of Dornyei’s model. However, my questionnaire consisted of more specific kinds of teacher feedback, having students rate which ones are helpful to them to maintain their motivation. In other words, it included the kinds of teacher feedback which could empower the students to maintain their intrinsic motivation. (See Appendix I for a copy of the feedback survey)

Delving into the narrower scope of feedback, we learn from the literature that a lot of the teacher feedback research has been devoted to teaching writing skills and the teacher’s written feedback. There is less research and data on teachers’ classroom discourse feedback/behavior and how it affects student motivation/empowerment. This is probably due to the fact that collecting the data on oral feedback is more difficult. Nevertheless, it is highly recommended that we pursue different ways of recording and evaluating our classroom oral feedback.

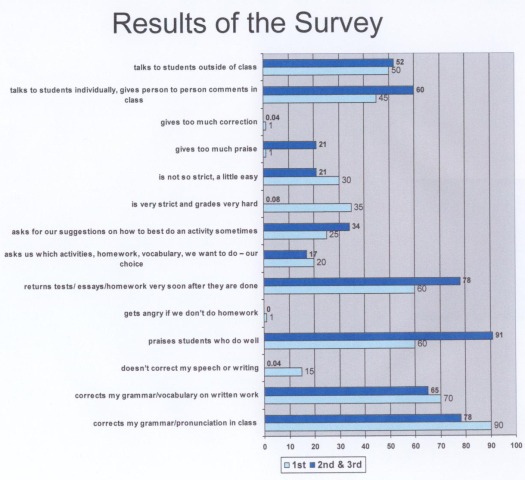

The feedback study I conducted consisted of a survey and student comments. Students were asked to select three teacher feedback situations which helped them the most to maintain motivation to learn (empowerment), and one reason they lost motivation. The list consisted of thirteen situations in which the students would write H (helps) DH (doesn’t help) and finally choose the three most helpful. Comments were welcomed at the end of the questionnaire. The total number of students who responded was forty-one. They were all Japanese, co-ed classes. The levels ranged from pre-intermediate to intermediate. Most were not English majors, so the classes represented a range of majors from law to business to education. Two of the classes were more motivated (based on records of attendance, completed homework, note taking in class, participation) The third class, which was pre-intermediate, was slightly less motivated (based on the same criteria).

Comprehensive results, which show the percentages of students who included those situations as one of their three most helpful ways, are shown in Appendix II. However, it is worth noting in this context that the majority of students from the less motivated class chose “corrections” as the best way to help motivate them. And half also selected “teacher talks to students individually …” Two students in this class of eleven preferred a “strict” teacher referring to homework and grades. Praise did not seem to be a major element in this class.

In the other two classes, which included more motivated students, two students out of thirty chose strictness as a help. A large number from these two classes chose “returns tests/homework quickly” and “gives choices …” or “asks for students’ suggestions” as helps in motivation.

Overwhelmingly, in all three groups, the most common help noted by students was corrections in class. As mentioned, the students could choose three situations that helped them, so “corrections” was one of the three. This was surprising to me, assuming that students wanted to talk more freely, that communication was more important than being corrected. But it seemed from the students’ point of view, not to be the case in these three classes. Another surprising result was regarding praise. Only seven students in a more motivated group of nineteen students ranked “praise” as the most helpful. Ninety percent in that group ranked it as one of their three helpful ways, and in the other group only sixty percent included praise. A likely explanation for the low numbers on praise is that teachers’ praise is not something familiar to Japanese students, whereas corrections are considered a common way to learn. Therefore, sometimes what teachers think is enabling students to be more motivated is actually counter to what and how they have been trained throughout their years of schooling.

It is difficult to change students’ ways of thinking once they enter university. Teachers at this level need to be aware of a possible dichotomy between what we think helps to empower students and what they have been taught to think helps them. Perhaps we need to explain to students why we offer fewer corrections and why we give praise and offer choices. The students in my classes are not used to being given choices, so they do not consciously value choices as much as I thought they would. With regard to choices, students often welcome the opportunity to participate in making decisions on topics, vocabulary study, certain classroom procedures, discussion questions, and other areas of participation where they can feel they have an investment in the learning process. These choices can enrich students’ sense of autonomy; therefore, we are empowering them by allowing them to participate.

As language teachers, shouldn’t we look at long-term empowerment as well as short-term daily empowerment? Long-term empowerment forces us to consider setting limits for students. Guiding them in the importance of meeting deadlines, managing time, accepting constructive criticism, teaching them to reflect through self-evaluations and questioning the way they learn and what they learn. These can be lifetime benefits, but may not appear to promote self-esteem in the short term.

Let us examine the use of praise from a wider perspective. We have recently seen that many educators in the US are re-evaluating the amount of praise given in building student self-esteem. Gottlieb (2011) in a recent article, concurs with therapists and professors of psychology reporting that due to too much praise and no negative feedback, US students are growing up more narcissistic, and not necessarily happy. In Gottlieb’s article she quotes a professor of psychology as saying “what starts off as healthy self-esteem can quickly morph into an inflated view of oneself …” She talks about “kids never getting negative feedback on their performances where all failures are reframed as ‘good tries.’” She cites a professor of psychology concluding that in early adulthood this can become a big problem with people thinking they are unusually special.

We have seen from experience how a little praise goes a long way in encouraging students, and building self-confidence, conversely, how over-praising can be condescending, perhaps diminishing power. As well, being overly critical can discourage further attempts or effort on the student’s part. Yet, constructive criticism can have empowering benefits.

Teachers who are focused on the lesson at hand, the content and pacing may not be aware of how seldom or how often they correct, comment, praise and offer suggestions to students. They may not be aware of how their discourse, instructions and explanations may be perceived as overly controlling, thus stifling empowerment. Hale (2011), in a study of classroom discourse, describes a series of exchanges in class in which his stepping back rather than explaining a student’s confusing utterance facilitated more student participation, and allowed the students to negotiate meaning to each other. His strategy to refrain from stepping in, and instead just elicit more clarification from the class empowered the students to take more initiative and explain the meaning of the student’s utterance. This technique is contrary to the traditional teacher-centered style – one that is described below as a conduit metaphor.

In their groundbreaking book on metaphors, Lakoff and Johnson (1980) argue that metaphors are not just poetic devices, but are so embedded in our everyday language that they shape our thinking in very consequential ways. Even our behavior and posture, distance from students and so on, can be metaphors. The authors’ “conduit” metaphor - a vehicle for inputting information almost mechanically without enough consideration of what is happening on the receiving end is noteworthy. Each language has its own systems of metaphors which shape meaning and concepts, ways of thinking, not simply form but meaning. Lakoff and Johnson argue that to understand each other, teacher and student, we have to negotiate meaning. We have to show mutual respect and be aware of our divergent worlds. We need to use metaphors creatively to build rapport, and most importantly, they argue that acting as a conduit, “where one person transmits a fixed clear proposition to another by means of expressions in a common language” ( p.231) is not negotiating meaning. As teachers we need to be aware of the kinds of metaphors that we use, the frequency with which we use metaphors, and are metaphors ourselves, and what they say to our students. Language of control, dominating language, does not empower the student, does not maintain motivation. When the teacher is a conduit of information without listening to or observing student reactions and questions, without negotiating meaning, empowerment is diminished. Chris Hale’s strategy, which was discussed above, seemed to be a conscious effort to deviate from the metaphor of the teacher as “conduit.”

How do teachers become more aware of the frequency and type of classroom feedback we give our students? In Hale’s study mentioned above, his method was to video the classroom discourse and transcribe the relevant segments. Grombczewska had a non-participating observer audio record the class and from the recording mark the frequency and types of feedback on a detailed chart. Some teachers use a questionnaire, for example, the rather rudimentary one I included in this paper. It certainly has a lot of room for improvement; however a sufficient number and variety of kinds of feedback in the questionnaire is important, as well as space for students to comment and time allotted for them to rate the feedback or behavior that helps them.

With regard to feedback and teacher’s talk, Murphey (2008), as a proponent of student action logs (feedback), argues that we often are not aware that students are learning something different from what we think they are getting out of our lessons. He suggests that we ask students, either as homework or as a short end-of-class reflection, to write down what they are doing in class, and how they like it. The teacher collects these and reads them every few weeks, possibly responding in the form of a newsletter to students with their comments included, and even using the responses of students to help in making the tests. Murphey mentions, among other advantages, that students become more involved if and when they have an impact on instruction. Also, students become more aware of the learning process, and asking them to write their reflections gives value to their input.

Concerning raising teachers’ awareness of their comments to students, I can recommend, besides Hale’s method, and Grombczewska’s and Murphy’s suggestions above, two other suggestions. One is to video your own classes, as Hale did, observing yourself in action, but focusing on your classroom feedback to students.

Another suggestion is to ask a colleague to observe your class and focus on the above kinds of behavior and feedback, even giving the observer a checklist to mark the type and frequency of certain feedback, and how students seemed to react to the feedback. I did try this and, I might add, with some success. I think it has a lot of potential for raising teachers’ awareness of strategies for empowerment.

So far, we have been examining two questions: what does empowering mean, and how can we as teachers raise our own awareness, and thus modify our classroom feedback to empower our students more? The third question: what new strategies for empowerment can we teach our students, will be taken up in this section.

There are many learner strategies which have been suggested for developing autonomous learners - confident and empowered students. Some of those strategies have already been touched upon in this paper, for example, student choices, time management in assignments, and indirectly, responsibility for learning and questioning, cooperation in group work, self evaluations, praise and encouragement.

These strategies are well known. However, there are also suggestions we can glean from our students which lead to greater learner-awareness. An original strategy suggested by my students on the feedback questionnaire was allowing students to discuss learning strategies from classmates during class. In groups, students discuss how they learn a particular skill, or skills, be it vocabulary development, listening, speaking, newspaper reading or difficult concepts. Students said they learn a lot from hearing how their classmates learn. This could be done after they have kept a learning diary for a week or so, reflecting on methods that are successful for them. In this way, sharing with classmates serves as a boost to maintaining motivation.

Learning diaries are invaluable for raising students’ awareness, responsibility, and autonomy in learning. There are many ways to do a learning diary, which is not the typical daily diary at all, as we have seen. Listening diaries (students write about what they have chosen to use as listening practice outside of class), and diaries to recognize individual learning styles are two useful ones.

Having students focus on self-praise and self-reward is a suggestion that arose from a class activity. Students should record learning occasions that call for praise, and then reward themselves with a break or something they like. A simple example might be if they finally got up the courage to attend a meeting in English (student English forums, chit chat clubs) where they knew they would be called on to give an opinion. If attendance was a conscious choice as well as an effort on their part, they deserve to praise themselves. The recognition alone will lead to more awareness of positive choices, solutions to problems, confidence building steps they take. Self-praise is quiet, unannounced praise which enriches intrinsic motivation and thus empowers the students to take charge of their learning.

A recent class activity involved a written assignment about an influential person in one’s life, regarding education. The students wrote about the people who motivated them to want to learn, to work hard, to study well, and not give up. These papers were then presented as reports in groups where the students listened to each other’s stories. They were quite powerful, and included parents, teachers, older brothers, and friends. One student said his high school teachers “put up a wall between the teacher and the students,” but that the one teacher who influenced him a lot did not put up any walls between teacher and students. Another negative comment from a student was that a certain teacher seemed to talk only to herself rather than to the students. Further on in the semester, it’s useful to remind the students of these influential people and have them recall, through a visualization activity, the lessons they learned from the people who motivated them to learn.

The reader has noticed already the inclusion of references from fields other than ESL/EFL. Other sources ranging from business articles, to magazine commentary on American schooling, to studies in the use of metaphor are documented in the paper. It is hoped that by not limiting the works cited, the common thread running through all of these divergent sources will reveal the widespread influence of empowerment in our lives.

As mentioned in the introduction, the initial, broad thinking about empowerment included relationships and interactions with people at work as well as students. However, the focus has been on teachers’ classroom feedback as a kind of empowerment, how to become more aware of our feedback styles and strategies we can teach our students. To do this, involved a lengthy discussion of terms so that we can see empowerment as it fits into motivation models, and how it plays out in the classroom.

It is hoped that by looking at empowerment as a companion to motivation we as teachers can gain a fresh understanding of our roles as facilitators in the classroom. It is also hoped that the suggestions offered for raising our awareness can help in accomplishing those goals which enable our students to be better learners. The term empowerment itself usually conjures positive images in the minds of English speakers. Whether it has the same positive metaphorical impact for other teachers and for our students may be a question to consider.

It is the context of both the intrinsic and the extrinsic motivation which has concerned us in our discussion of empowerment. The teacher’s awareness of the two, the value each serves, and how they differ are keys to empowering students. Enabling intrinsic motivation with confidence-building and autonomous learning strategies has long-lasting effects. Enabling the student’s extrinsic motivation with self-awareness, praise, modified discourse, and facilitation techniques is practical and efficient in the short-term.

As a final thought I return to the discussion with a colleague that was mentioned in the beginning. A person really empowers another when he/she can make you feel “it was your idea” all along. In other words, conveying ownership, and that means sharing control, whether it is about ideas, or the learning process, is a necessary goal if we are to enable our students to maintain their motivation to learn.

Bordonaro, Karen (1999). Encouraging students to become stakeholders in the ESL classroom. The Internet TESL Journal, Vol. V,( No. 9), September 1999. Retrieved Aug. 2011 from: http://iteslj.org/Techniques/Bordonaro-Stakeholder.html

Bryant, Adam, (2011, August 29). A key to doing well here? Be nice. International Herald Tribune, p. 17.

Dornyei, Zoltan (2001). Motivational strategies in the language classroom. Cambridge: UK. Cambridge University Press.

Gottlieb, Lori (July/August, 2011). How the cult of self-esteem is ruining our kids. The Atlantic, vol.308 (no.1), 64-78.

Grombczewska, Marlena (2011). The relationship between teacher’s feedback and students’ motivation. Humanizing Language Teaching. Retrieved Aug, 30, 2011 from: old.hltmag.co.uk/jun11/stud.htm

Hale, Chris (2011) Breaking with the IRF and EPA: Facilitating student-initiated talk. The Language Teacher, vol.35 (no.5).

Harvey, L. and Burrows, A. (1992). Empowering students, New Academic, 1, (no 3), Summer, p. 1ff. Retrieved Sept. 5, 2011 from:

www.qualityresearchinternational.com/glossary/empowerment.htm

Lakoff, George and Johnson, Mark (1980). Metaphors we live by. Chicago, Il: The University of Chicago Press.

Larson-Freeman, Diane (2000). Techniques and principles in language teaching. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Murphey, Tim (2008). Why don’t teachers learn what learners learn? Taking the guess work out with action logs. English Teaching Forum (on-line). Retrieved August 30, 2011 from:

www.kuis.ac.jp

Please write H (helps) for the feedback situations that may help or motivate you to learn. The teacher

- _______ corrects my grammar/pronunciation in class

- _______ corrects my grammar/vocabulary on written work

- _______ doesn’t correct my speech or writing

- _______ praises students who do well

- _______ gets angry if we don’t do homework

- _______ returns tests/ essays/homework very soon after they are done

- _______ asks us which activities, homework, vocabulary, we want to do – our choice

- _______ asks for our suggestions on how to best do an activity sometimes

- _______ is very strict and grades very hard

- _______ is not so strict, a little easy

- _______ gives too much praise

- _______ gives too much correction

- _______ talks to students individually, gives person to person comments in class

- _______ talks to students outside of class

Now, look again and choose the three situations that help you the most to stay motivated to learn. Please add any comments about what teachers do or say that help you to learn best.

Please check the How the Motivate your Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Building Positive Group Dynamics course at Pilgrims website.

|