Developing Phonological Awareness in Young Learners

Cindy Chia-Hui Shen, Taiwan

Cindy Shen obtained her Master degree from the Department of English Instruction in Taipei Municipal University of Education, and now she is a PhD student at the Department of English, National Taiwan Normal University. She teaches at Taipei Municipal Fuan Elementary School. Her research interests include SLA, reading strategies, and computer-assisted language learning. E-mail: cindy422@tp.edu.tw

Menu

Introduction

Phonological awareness and foreign language learning

The role of phonological awareness and reading proficiency

Phonological awareness and L2 literacy development

The effectiveness of phonological awareness instruction

Phonological awareness activities

Conclusion

References

During the early literacy period, phonological awareness has been recognized as a perquisite and one of the key precursor skills for learning to read (Hu & Schuele, 2005). In other words, children who fail to acquire phonological awareness have difficulty in mastering orthographic representations. Previous studies have significantly supported the causal and predictive relation between phonological awareness and children’s ability of decoding and spelling; therefore, it is important to design activities combined with phonological awareness in language classrooms. Students who lack the ability to analyze the sound structure of words display deficiencies in decoding English words. These deficiencies could affect learners’ L2 reading ability significantly (Shaywitz, 1996). In Taiwan, for example, it has become a trend to learn English at an early age. There are many cities and countries have required elementary school students (aged 7-12) start to learn English with alphabets and phonics from the first grade. However, few of the curricula, childhood education, and learning contexts have sufficient instructions in phonological awareness. Many language instructors do not have a strong sense of phonological awareness in integrating into lesson plans based on students’ cognitive development.

With respect to low achievers, some teachers may assume these children do not make great effort in studying, or they are the so-called ‘culturally disadvantaged children.’ However, Ganschow, Sparks, Javorsky, Pohlman, and Bishop-Marbury (1991) argued that it is because they have linguistic coding problem, i.e., subtle phonological, syntactic, and semantic difficulties in their native language. This “linguistic coding deficit” hypothesis (LCDH) was verified by comparing successful and unsuccessful foreign language learners in phonological awareness. Based on the findings, the authors suggested that the presence of difficulties with phonological and syntactic skills in one’s native language may be the indicators and precursors of foreign language difficulties.

As Hu & Schuele (2005) pointed out, poor phonological awareness might slow nonnative acquisition of vocabulary via difficulty in constructing new phonological representations for new words. Children who were more phonologically aware acquired new reading vocabulary significantly faster than those who were less phonologically aware. In addition, short memory, word blending and segmentation, letter naming, and producing rhymes are the key factors of phonological awareness. The result indicated that children with poor phonological awareness of their native language had difficulty in associative learning new vocabulary in a nonnative language.

Students who are unaware of words consisting of a series of discrete sounds have difficulties in reading and writing. Those students without the ability to analyze the sound structure of words display deficiencies in decoding English words. These deficiencies could affect their L2 reading ability greatly. This pattern of deficits is in close correspondence with the dominant phonological deficit explanation of difficulties in learning to read (Shaywitz, 1996).

It is an important issue that phonological skills are essential to the novice readers. Without the ability of phonological awareness, readers cannot decode the words and find an interrelationship between letters and sounds; therefore, it is necessary for readers, particularly EFL readers with limited target language exposures, to have sufficient training and instruction of phonological awareness activities in class, e.g., phonological discrimination, phonological awareness, memory, and retrieval. Moreover, storytelling, rhyming, word blending training are all suggested to enhance students’ phonological awareness. Children with low phonological awareness are recommended to receive instruction in phonological awareness consistently so that their phonological abilities and word recognition skills can be enhanced.

Phonological representations can be linked to orthographic representations from the early literacy. These representations assist in forming orthographic representations, therefore creating a unified form representation (Landi, Perfetti, Bolger, Dunlap, & Foorman, 2006). According to Bishop’s (1997) statement, there are two complementary skills of speech perception: the ability to distinguish different sounds (phonological discrimination), and the ability to treat sounds that are acoustically different as equivalent (phoneme constancy).

Some children with expressive phonological problems applying immature perceptual strategies, i.e., they don’t understand that speech can be analyzed into smaller syllabic units. They have difficulty perceiving phonological constancy, for example, the words sun and sit, as having the same initial sound. Another example is the phoneme /t/, the words button, stop, top, pot, tea, two, and writer for specific language impairment (SLI) children, who have the ability to discriminate phonological contrasts, but they cannot distinguish speech sounds. This argument was supported by Tallal’s (1984) hypothesis of a “temporal processing” impairment. When auditory stimuli are either brief or rapid, children with SLI have difficulty in discriminating them.

Regarding the implications of these studies for teachers, initial reading instruction for struggling readers can be organized by phonological awareness as an entry to successful reading. Students with reading disabilities can be improved in phonological awareness when they receive appropriate instruction, e.g., Word Parts. The size of the unit being manipulated refers to how large or how small a ‘chunk’ the student orally manipulate. The syllable in a word is a larger chunk than its individual sounds (phonemes). O’Shaughnessy and Swanson (2000) suggested that readers respond better to remedial strategies that use larger phonological units (i.e., rimes), reducing the memory demands of blending sounds together to form words.

According to Adams (1990), it is relatively easy to break the onset away from the rime, but it is relatively difficult to break either the onset or the rime into its phonemic components. The reason is that separate sounds merge into words and are not easy to segment them into individual sounds in spoken language. Furthermore, the pronunciation of individual vowels and vowel digraphs are much more difficult for beginning readers than vowel sounds with rimes with consistency. In other words, the awareness of rimes reduces the memory demands of sound blending to form new words. Another supporting idea is from the results in Hines, Speece, Walker, and DaDeppo’s (2007) study, suggesting that instruction with onset-rime yielded great maintenance and positive near transfer (novel words containing instructed rimes), but not for far transfer (novel word derived from uninstructed rimes).

When dealing with remedial instruction for students with foreign language learning difficulty, strategic phonological activities are particularly needed, including multiple exposures to the printed word reading and relevant training activities. After being received these in-class motivating activities, young learners can quickly pick up the sounds and get much familiar with the sounds, e.g., playing songs with similar tunes and repeated words occurrences may enhance long-term memory in children with SLI (Fazio, 1997). Moreover, using analogy to read words requires onset-rime segmentation and blending skills. For the heterogeneous language proficiency learners, poor readers read words by segmenting individual sounds, whereas more advanced readers read by processing chunks of letters. Children need to learn how to apply analogy to read when encountering unknown or unfamiliar words.

Here are some ways to bridge the gaps between successful reading and phonological awareness listed as follows. I used phonological awareness activities with the second graders at elementary school and examined if any of them need further instruction for remedial teaching.

1. Can you rhyme?

This game encourages students to listen to sound and contextual clues to generate a rhyming word that fits in a rhyme phrase. To introduce this game, the teacher guide students to say several rhyme phrases aloud. Then, challenge students to complete each rhyme by telling a rhyming word. For example, The king with a ring likes to __________. (sing)

2. Word blending.

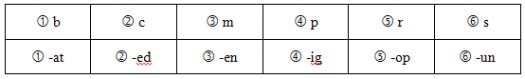

The teacher invites two students as a group. Each student rolls one dice, and they blend the initial sound and the rhyming sound together. The teacher administers the one who pronounces the words quickly and accurately. For example, number m plus op makes the word mop.

3. Substitutions.

Followed by the teaching recommendation from the Hines et al (2007), rimes and onset should be taught before phoneme segmentation; therefore, I asked these EFL learners to transfer their prior knowledge about familiar sounds to the uninstructed rime patterns of novel words, e.g., a child could identify the common rime with known word cat and substitute the initial /h/ sound for /c/ to decode the novel word hat. Students can play tongue twister, such as

“a big black bug bit the big black bear, but the big black bear bit the big

black bug.” and sing nursery rhymes, e.g,

“Ring around the rosie,

A pocket full of posies,

Ashes, ashes,

We all fall down! ”

/d/ ding around the doise

/p/ ping around the poise

/cl/, /scr/....

In addition, reading stories for children is also an effective way to help them to cultivate phonological awareness ability.

4. Sing short vowels (CVC pattern) rap.

Students are requested to listen and fill-in the blanks. For example,

“The fat cat sat on the mat.

The fet cet set on the met.

The fit cit sit on the mit.

The fot cot sot on the mot.

The fut cut sut on the mut.”

5. Technology-based games.

With the advancement of technology in the tablet PC and smartphones, abundant software applications (apps) for developing phonological awareness, such as Phonics Studio, Endless ABC, are continuously invented. These apps not only focus on individual difference and personal learning pace, but also enrich the content of curricula and students’ learning outcomes in phonological awareness activities.

In brief, the difficulties of learning foreign language seem to be the disability in decoding phonological units from the auditory input and in generalizing phonological rules in multiple learning contexts. Thus, instructors should provide prompt assistance and contextual exposures of phonological awareness for EFL learners so that they could be strategic and successful foreign language learners when encountering unfamiliar or unknown words.

Adams, M. J. (1990). Beginning to Read: Thinking and Learning about Print. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Bishop, D. V. M. (1997). Uncommon Understanding: Development and Disorders of

Language Comprehension in Children. East Sussex, UK: Psychology Press.

Fazio, B. B. (1997). Learning a new poem: Memory for connected speech and

phonological awareness in low-income children with and without specific language

impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 40, 1285-1297.

Ganschow, L., Sparks, R. L., Javorsky, J., Pohlman, J. & Bishop-Marbury, A. (1991).

Identifying native language difficulties among foreign language learners in college: A

“foreign” language learning disabilities? Journal of Learning Disabilities, 24,

530-541.

Hines, S. J., Speece, D. L., Walker, C. Y., & DaDeppo, L. M. W. (2007). Assessing

more than you teach: The difficult case of transfer. Reading and Writing, 20, 539-552.

Hu, C. F., & Schuele, C. M. (2005). Learning nonnative names: The effect of poor

native PA. Applied Psycholinguistics, 26, 343-362.

Landi, N., Perfetti, C. A., Bolger, D. J., Dunlap, S., & Foorman, B. R. (2006). The role

of discourse context in developing word form representations: A paradoxical relation

between reading and learning. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 94,

114-133.

O’Shaughnessy, T. E., & Swanson, H. L. (2000). A comparison of two reading

interventions for children with learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities,

33, 257-278.

Shaywitz, S. E. (1996). Dyslexia. Scientific American, 275, 98-104.

Tallal, P. (1984). Temporal or phonetic processing deficit in dyslexia? That is the

question. Applied Psycholinguistics, 5, 167-169.

Please check the Methodology and Language for Kindergarten Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Methodology and Language for Primary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Pronunciation course at Pilgrims website.

|