Adjusting the ELT Class to a Therapy Session

Saeed Ketabi and Reza Zabihi, Iran

Saeed Ketabi is an associate professor in TEFL at English Department, Faculty of Foreign Languages, university of Isfahan, Iran. His main areas of research are teaching methodology and curriculum development, affiliation: University of Isfahan, Isfahan, Iran.

Email: ketabi@fgn.ui.ac.ir

Reza Zabihi is a PhD candidate of Applied Linguistics in University of Isfahan, Isfahan, Iran. He is also a member of Iran’s National Elites Foundation (INEF). His major research interests include syllabus design as well as sociolinguistic and psycholinguistic studies, affiliation: University of Isfahan, Isfahan, Iran.

Email: zabihi@hotmail.com , zabihi0046@hotmail.com

Menu

Initial thoughts

Reflections

References

It is widely acknowledged that once youngsters step into the threshold of the school life, they are incrementally being affected by their teachers, peers, and adults other than their parents (Berndt & Keefe, 1992; Eccles, 1993; Freeman & Brown, 2001; Fugligni, Eccles, Barber, & Clements, 2001; Haynie, South, & Bose, 2006). That is why it has recurrently been recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) that schools should be granted a high credibility with the students’ parents and community members. Sadly, however, one also has to acknowledge the fact that sometimes a large number of these youngsters, though no fault of their own, are incapable of putting into use their full potential in a most socially commendable manner due to the absence of proper instruction and motivation (Ardelt & Day, 2002).

By and large, individuals with a variety of mental disorders often seek help from expert counselors who can soothe the pain and open new horizons in the life of their clients. In this connection, the idea of educational therapy (Caspari, 1970) came into being as a specialized educational and therapeutic form of instruction which is tailored to meet the specific needs of students. Put another way, in educational therapy the teacher plays the role of a therapist, while the problematic learner plays the role of a client. An educational therapist is characterized as “a professional who combines educational and therapeutic approaches for evaluation, remediation, case management, and communication/advocacy on behalf of children, adolescents and adults with learning disabilities or learning problems” (www.aetonline.org).

The areas which are of great concern in educational therapy encompass depression, learning difficulties, communication problems, and deficiency in building interpersonal ties in society, alongside other problems which can jeopardize individuals’ mental health (Jarvis, 2005). Hence, at any given point in time, there is a felt need for enhancing individuals’ quality of life in the context of education. Suffice it to say that literature is replete with the research studies that advocate the promotion of life quality in the context of education (e.g., Brooks, 2001; Francis, 2007; Goody, 2001; Larson & Cook, 1985; Matthews, 2006; Noddings, 2003; Radja, Hoffmann, & Bakhshi, 2008; Spence, 2003; Walker, 1999). In addition, Spence (2003) argues that any attempt made at improving students’ life skills, including their decision making skills as well as their abilities to construct positive values and self-concept, can help them optimize the contributions they make to the society.

Obviously, in order to improve people’s quality of life many factors should be taken into consideration. These factors include, inter alia, social relations, safety, mental health, happiness, human rights, freedom, marriage success, emotional competencies and job satisfaction. It is well accepted that the enhancement of these factors should be seriously taken into account in the context of education. As one of the forerunners of this liberatory movement, humanistic education has given precedence to the unique role that should be adopted by any education system to empower individuals to lead a well-deserved life. As Whitehead (1929) puts it, “there is only one subject-matter for education, and that is life in all its manifestations” (p. 6). Therefore, any practice that triggers teaching life skills is a value-addition enterprise which enables individuals to realize their own real self, adapt socially and emotionally, and become empowered to evaluate their actual and potential capabilities.

Under this account, many educational philosophers such as, to name just a few, Dewey (1897), Walters (1997), Krishnamurti (1981), and Freire (1998) have contended that programs specifically designed to improve the lives of individuals must become part and parcel of any education system. In this respect, all systems of education must prepare their members for meeting the challenges that individuals might face in their lives in advance of making them ready for employment or other personal gains. Following the lines of these philosophers, many researchers have encouraged the improvement of several life skills in the context of education. For instance, to provide some points of reference, Noddings (2003) considers the improvement of students’ happiness as an indisputable aim of education. Similarly, Walker (1999) regards self-determination as the primary goal of education to be achieved. Moreover, Matthews (2006) argues that attempts made at enhancing the emotional abilities of students should form integral parts of education. Last, but by no means least, while Hare (1999) puts more emphasis on improving critical thinking, Winch (1999) prioritizes the promotion of autonomy. These researchers have offered us numerous rich accounts of both the rate and route of enhancing these life skills.

Alongside other life skills, the above competencies are characterized as “skills that help an individual be successful in living a productive and satisfying life” (Hendricks, 1996, p. 4). By the same token, the Mental Health Promotion and Policy (MHP) team in WHO defines life skills as “the abilities for adaptive and positive behavior that enable individuals to deal effectively with the demands and challenges of everyday life” (WHO, 1999). Accordingly, the WHO has proposed ten core life skills including, decision making, problem solving, coping with emotions, coping with stress, critical thinking, creative thinking, interpersonal relationship skills, effective communication, self-awareness, and empathy and understanding. This is not to suggest that content area should be sidestepped, or even waived, at the cost of improving students’ life skills; rather, the idea of life skills training brings us to a conglomerate view of education in which teaching does not merely encompass reaching students to academic excellence, but it also tries to integrate the consideration of students’ emotions, relationships, attitudes, thinking styles, feelings, and values into different types of curricula.

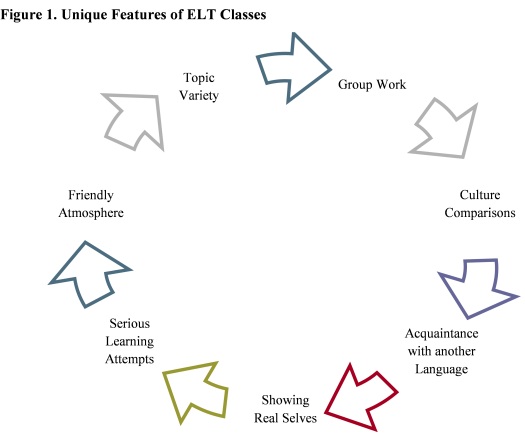

One particular case in point, as the primary concern of this paper, is the ELT curriculum that offers distinctive potentials for the conduction of educational therapy and life skills interventions. These unique features include, inter alia, discussing a large number of social, scientific, and political topics, holding pair work and group work in class, comparing two cultures, getting acquainted with the words and grammar of another language, speaking in another language in which one can show their own real self, taking language learning very seriously, and having a funny and friendly atmosphere for learning (Pishghadam, 2011). Figure 1 summarizes the unique features of ELT classes.

Nonetheless, it seems that the aforementioned influential undertakings, i.e. educational therapy and life skills training, have left the field of English language teaching untouched. In other words, despite the facts that ELT is an interdisciplinary field and that ELT classes mostly enjoy a vast number of distinctive features which can smooth the way for the enhancement of several life skills and the amelioration of many emotional, behavioral, and learning problems, it seems that ELT professionals should go beyond the language-and-life orientation that currently prevail ELT towards a life-and-language outlook. With that in mind, in the present study the authors took a mixed method approach to analyzing pre-service English teachers’ conceptions about the extent to which ELT classes should endorse or shy away from embracing the methods and techniques that are typically used in educational therapy and life skills training.

Ardelt, M., & Day, L. (2002). Parents, siblings, and peers: Close social relationships and adolescent deviance. Journal of Early Adolescence, 22, 310-349.

Berndt, T. J., & Keefe, K. (1992). Friend’s influence on adolescents’ perceptions of themselves at school. In D. Schunk & J. Meece (Eds.), Student perceptions in the classroom (pp. 51-73). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Brooks, R. (2001) Fostering motivation, hope, and resilience in children with learning disorders. Annals of Dyslexia, 51, 9-20.

Dewey, J. (1897). My pedagogic creed. The School Journal, 54 (3), 77-80.

Eccles, J. S. (1993). School and family effects on the ontogeny of children’s interests, self-perceptions, and activity choice. In J. Jacobs (Ed.), Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1992: Developmental perspectives on motivation (pp. 145-208). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Francis, M. (2007). Life skills education. www.changingminds.org.

Freeman, H. & Brown, B. B. (2001). Primary attachment to parents and peers during adolescence: Differences by attachment style. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 30, 653-674.

Freire, P. (1998). Pedagogy of freedom: Ethics, democracy, and civic courage. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Fugligni, A. J., Eccles, J. S., Barber, B. L., & Clements, P. (2001). Early adolescent peer orientation and adjustment during high school. Developmental Psychology, 37, 28-36.

Goody, J. (2001). Competencies and education: Contextual diversity. In: D. S. Rychen, & L.H. Salganik (Eds.), Defining and selecting key competencies. Gottingen, Hogrefe and Huber Publications.

Hare, W. (1999). Critical thinking as an aim of education. In R. Marples (Ed.), The aims of education. London: Routledge.

Haynie, D. L., South, S. J., & Bose, S. (2006). The company you keep: Adolescent mobility and peer behavior. Sociological Inquiry, 76, 397-426.

Hosseini, A., & Navari, S. (in press). Educational therapy: On the importance of second language communication on overcoming depression. Proceedings of the 1st Conference on Language Learning & Teaching: An Interdisciplinary Approach (LLT-IA).

Jarvis, M. (2005). The psychology of effective learning and teaching. London, UK: Nelson Thrones Ltd.

Krishnamurti, J. (1981). Education and the significance of life. HarperCollins Publishers.

Larson, D. G., & Cook, R. E. (1985). Life-skills training in education. Journal of Group Psychotherapy, Psychodrama, & Sociometry, 38(1), 11-22.

Matthews, B. (2006). Engaging education: Developing emotional literacy, equity, and co-education. McGraw-Hill Education: Open University Press.

Noddings, N. (2003). Happiness and education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pishghadam, R. (2011). Introducing Applied ELT as a new approach in second/foreign language studies. Iranian EFL Journal, 7 (2), 9-20.

Radja, K., Hoffmann, A. M., & Bakhshi, P. (2008). Education and capabilities approach: Life skills education as a bridge to human capabilities.

http://ethique.perso.neuf.fr/Hoffmann_Radja_Bakhshi.pdf

Spence, S. H. (2003). Social skills training with children and young people: Theory, evidence and practice. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 8(2), 84-96.

Walker, J. C. (1999). Self-determination as an educational aim. In R. Marples (Ed.), The aims of education. London: Routledge.

Walters, J. D. (1997). Education for life: Preparing children to meet the challenges. Crystal Clarity Publishers.

Winch, C. (1999). Autonomy as an educational aim. In R. Marples (Ed.), The aims of education. London: Routledge.

WHO (1999). Partners in life skills education: Conclusions from a United Nations inter-agency meeting. Geneva: Department of Mental Health, Social Change and Mental Health Cluster, WHO.

Please check the Methodology and Language for Secondary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Dealing with Difficult Learners course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Building Positive Group Dynamics course at Pilgrims website.

|