‘Chunks’ and Generative Grammar

Manjula Duraiswamy, India

Manjula Duraiswamy has been a teacher, teacher trainer and senior editor with two different publishing houses. She is an Examiner for the University of Cambridge, Local Examinations Syndicate and is a Language Trainer for corporate clients. She enjoys travel, writing and music and is deeply interested in language development across a variety of contexts. She completed her Doctoral studies on “The Role of Chunks in Second Language Acquisition”. E-mail: manjula92001@yahoo.co.in

Menu

Introduction

Using chunks in the classroom

Kaleidoscope – chunks in use

Generative grammar

Bibliography

Language is a pattern, a kaleidoscope of designs that emerges from a human context to express specific needs. These needs can be related to seeking information, giving instructions or describing a situation, all based on a basic human desire to fit in pieces in a recognizable pattern. If language is based on patterning then all languages should follow an underlying map which allows permissible combinations. This universal map or universal grammar (based on Chomsky’s theory about Universal Grammar) forms a strong unifying strand that encourages language acquisition.

Language is not merely a mechanical combination of different items but is meaningful application of sentence patterns and can be submitted to a process of substitution. Language acquisition takes place relatively easily in human beings as compared to chimps taught to communicate in human language. This could be because human beings have universal patterning to support language acquisition, while chimps do not appear to have any basis for patterning making it much more difficult to bring about language skills. In short, the basis for patterning, the glass chips in a kaleidoscope, should be present for the kaleidoscope to create patterns, human beings with their innate sense of language design can grasp language better than chimps.

Hence, if we think of language as patterning then language production is the design that emerges when the kaleidoscope is turned about (social context). This theory throws up several fundamental principles:

- Language patterning is based on context.

- It is governed by universal principles.

- Patterning has almost limitless possibilities.

- Some situations can throw up better patterns as compared to others.

- Language is not merely a mechanical combination of different items but is the meaningful application of sentence patterns which can be submitted to a process of substitution.

The sentence, ‘The child ate the cake’ by substitution could yield a wide range of sentences:

| Meera |

hit/ate/liked |

the mosquito |

| She |

the thread |

| He |

the orange |

Language acquisition occurs when the underlying patterns are recognized and used productively to generate fresh samples of language. In addition, apart from recognizing the pattern, language acquisition is enhanced when chunks from the pattern are used in other patterns to convey new ideas, governed by features of appropriacy and context.

These two aspects of sentence patterns and substitution form an important aspect of the manner in which prefabricated chunks combine to generate language output. In addition language acquisition is closely linked to the lexical structure of a language rather than with isolated words. In short, understanding the context of a particular pattern and its constituents can lead to efficient language development.

A kaleidoscope is a tube of mirrors containing loose coloured beads, tiny marbles or other small coloured objects. It is based on hyperbolic geometry and operates on the principle of multiple reflections. When light enters from one end, images are reflected off the mirrors and as the tube is rotated, the tumbling of the coloured objects presents the viewer with varying patterns of beautiful forms.

The word ‘kaleidoscope’ was coined in 1817 by its inventor Sir David Brewster and was based on the Greek meaning for beauty and form, broadly translating to ‘observer of beautiful forms’.

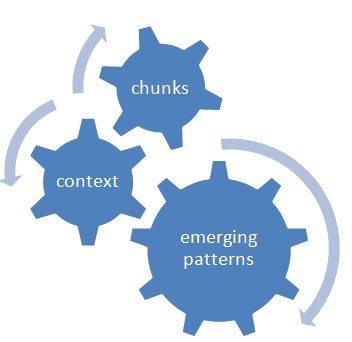

Language acquisition is enhanced when chunks from one pattern are used in other patterns to convey new ideas in the same way that the coloured pieces of glass in a kaleidoscope create fresh patterns each time the tube is turned. This process can be represented diagrammatically in this way:

Taking the analogy of the kaleidoscope further, if context is the tube then ‘noticing ‘patterns, or syntax, and the use of constituent chunks in particular contexts can lead to enhancement of linguistic abilities.

Formal grammars with their centre in syntax will need to incorporate generative semantics to make them useful in speech and writing. According to Fillmore (cited in Nattinger and De Carrico 1992) “What do they need to know when they use it? It is not grammaticality or acceptability in the non-acceptable uses, but rather contextual acceptability”.

Chunks and their implications for generative grammar provide explanations under language parameters enabling the learner to organize and relate scattered and isolated knowledge. Examples of this phenomenon can be found in:

- Bharati is older than Preeta.

- I have a newer phone than Bharati.

- You need a newer model.

- She sings more joyfully than tunefully.

- More than knowledge it is sensitiveness that is important.

- A sweeter girl than Geeta would be hard to find.

The idea of generative grammar as it relates to chunks is based on predictions of the situations in which the learner is likely to operate. A description of the linguistic features and behavioural analysis provides support for language development using chunks and focuses on what is most relevant to a particular group of learners, so that relevance and motivation are ensured and linguistically heterogeneous material reflecting natural choice, is selected.

Grammar is linked to reinforcement and consolidation as the recycling of language is inherent with language learning opportunities. The direct teaching of grammar should be the conclusion, not the starting point of a teaching unit, so that learners have already used the language forms in several meaningful contexts before being asked to study the underlying grammar.

In a learner centered classroom, where we believe that our students learn better when they participate actively in the learning process, opportunity should be provided for their active participation in the formulation of the rules underlying the language forms. Grammar is acquired through a process of natural growth and limited periods of conscious learning. In order to optimize opportunity for the acquisition of grammar, the teacher should:

- provide a wide range of inputs related to learner experiences

- direct learner attention to content with the help of games and activities ensuring that emphasis is on language

Aitchison, J. Words in the Mind: An introduction to the Mental Lexicon. Blackwell P, 1987. Print.

---. Linguistics: An Introduction. Hodder Headline P, 1990. Print.

Bruner, J. The social context of language acquisition. 1981. Print. Language and Communication.

---. Child’s Talk: Learning to use Language. Oxford: Oxford University P, 1983. Print.

Cameron L. Teaching Languages to Young Learners. Cambridge: Cambridge University P, 2001. Print.

Ellis, R. The role of input in language acquisition: some implications for second language teaching. 1981. Print. Applied Linguistics.

Nattinger and Jeanette S. De Carrico. Lexical Phrases and Language Teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Please check the Methodology and Language for Primary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Methodology and Language for Secondary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

|