EFL Learners’ Creativity and Critical Thinking: Are They Associated?

Mansoor Fahim and Alireza Zaker, Iran

Mansoor Fahim is an associate professor of TEFL at Allameh Tabataba'i University, Tehran, Iran from 1981 to 2008. Currently, he runs Research Methods, Psycholinguistics, Applied Linguistics, Second Language Acquisition, and Seminar classes at M.A. level, in addition to First Language Acquisition, Psycholinguistics, and Discourse Analysis at Ph.D. level. He has published several articles and books, mostly in the field of TEFL, and has translated some books into Persian.

Alireza Zaker is currently a Ph.D. student of TEFL, Islamic Azad University, Science and Research Branch, Tehran, Iran. His specific areas of ELT research include Language Testing, Research Methodology, Educational Measurement, and Critical Thinking. He has published in international academic journals and presented in several national and international ELT conferences.

Menu

Abstract

Introduction

Review of literature

Method

Participants

Instrumentation

Creativity questionnaire

Critical thinking questionnaire

Procedure

Results

Checking the assumptions of linear correlation

Linear relation between variables

Normality of the distributions

Homoscedasticity

The research question

Discussion and conclusion

References

This study set out to investigate the relationship between Creativity (CR) and Critical Thinking (CT) among EFL learners. To this end, a group of 182 male and female learners, between the ages of 19 and 40, majoring in English Translation and English Literature at Islamic Azad University, Central Tehran and Roudehen were randomly selected and were given two questionnaires: a questionnaire of CR developed by Zaker (2013) and a questionnaire of CT developed by Honey (2000). The relationship between CR and CT was investigated using Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficient. The results indicated that there is a significant and positive relationship between EFL learners’ CR and CT (r = 0.825, p < 0.05) regardless of gender. Drawing upon the findings, some pedagogical implications are presented, and finally, some avenues for future research are highlighted.

Keywords: creativity, critical thinking, effective learning, student-centered methodology

Investigation into the process of learning a new language calls for considering two basic aspects. The first domain is the practice of language teaching and the methodology supporting it. In addition to pedagogy, its assumptions, and its frameworks, the personal and mental characteristic of the learners impact SLA in an unquestionable fashion. These human factors seem to have critical importance where we seek to develop a theory for teaching language and improve the productivity of classroom practice (Lightbown & Spada, 2006).

Creativity (CR) and Critical Thinking (CT) not only are among the hot topics in the TEFL profession, but are also widely acknowledged to be among the metacognitive factors which substantially impact, influence, and shape the process of learning English as a second/foreign language (Connolly, 2000; Kabilan, 2000; Sarsani, 2006). The abovementioned premise is in line with Kabilan’s (2000) statement where he argues that for learners to become proficient in a language, they should exercise creative and critical thinking through the language being learned.

There is a growing body of research in our field that aims at conducting further investigation into the nature of CR and CT separately and the way each one promotes learning a new language. Nevertheless, the critical issue which needs to be addressed is if the level of CR is associated with the level of CT in a systematic fashion. This point was the main driving force for the researchers of the present study to investigate the relationship between EFL learners’ CR and CT. In order to achieve the objective of the study, the subsequent research question was posed:

Q1: Is there any significant relationship between EFL learners’ creativity and critical thinking?

The current trends in TEFL advocate a student-centred methodology and give great value to learner autonomy (Benson, 2003; Dickinson, 1992; Holec, 1981; Nosratinia & Zaker, 2013) whose enrichment in second language classes according to Ku (2009) calls for maximizing learners’ potential for learning by dint of critical reflection. In this regard, learners are expected to surpass absorbing knowledge and learn to improve skills, appraise information, inspect alternative evidence, and argue with defensible reasons (Nosratinia & Zaker, 2013). Some psychologists, as mentioned by Fahim and Sheikhy (2011), describe CT as a cognitive process that might have a lot to contribute when it comes to autonomous learning.

It seems reasonable to expect that for developing the potential for learning through critical reflection, learners would need CT and CT-oriented training. There is considerable literature which recognizes CT as a principal competence for (language) learners to obtain (Connolly, 2000; Davidson, 1998; Davidson & Dunham, 1997). According to Wagner (1997) no one might be able to develop mastery in any area without engagement in effortful thinking processes. Craik and Lockhart (as cited in Nation & Macalister, 2010, p. 60) while focus on the significance of processing an item as profoundly as possible and the way this process contributes to learning, sensibly argue that “the quantity of learning depends on the quality of mental activity at the moment of learning”.

Socrates, the prominent figure of thinking, began the practice of CT through reflectively questioning common beliefs and expectations, and distinguishing beliefs that are reasonable and logical from those which are not supported by firm evidence or rational justification (Cosgrove, 2009). Inspection of the studies on CT leads us to a myriad of definitions regarding CT. CT, regarded as an advanced level of cognition, has been defined as "a purposeful, self-regulatory judgement which results in interpretation, analysis evaluation, and inference, as well as explanations of evidential, conceptual, methodological or contextual consideration upon which the judgement is based" (Astleitner, 2002, p. 53). Willingham (2008) argues that CT is about looking at matters from different perspectives which would allow evidence to change opinions as well as substantiating claims.

CR is another mental characteristic whose attribution to language learning is plenteous (Albert & Kormos, 2011). Pink (as cited in Rao & Prasad, 2009, p. 31) argues that humankind is “entering a new age where creative thinking is becoming increasingly important”. CR has also been considered to be “about developing skills in thinking” (Sarsani, 2005, p. 134). The field of CR as it is presently known has been introduced and developed by the attempts of Guilford and Torrance (Sternberg, 2009). Russ and Fiorelli (2010) maintain that CR comprises those abilities that enable an individual to “understand the information, think out of the box, break a set, and transform the known patterns into the unknown new ones” (p. 236).

As defined by Lubart (1999), CR, by and large, is considered to be the capacity to produce novel and original creations which are considered suitable for the attributes and peculiarities of a task at hand, where these products might be related to different concepts, perspectives, and innovations. These creations and products are expected to be “original as they should not be just a mere copy of what already exists” (Lubart & Guignard, 2004, p. 43). Thus, regarding learning, CR would enable the learners to respond appropriately and relevantly to the myriad of situations that can be faced in the day-to-day life for which no predetermined and fixed language-wise responses are available.

Human beings are all equipped with an enormous inner potential for CR and learning (Marashi & Dadari, 2012), and CR is believed to be subject to improvement “at all ages and in all fields of human endeavor” (Sarsani, 2005, p. 47). On the other hand, education is expected to “enable people to generate and implement new ideas and to adapt positively to different changes in order to survive in the current world” (Craft, Jeffrey, & Leibling, 2001, p. ix). Accordingly, it seems that the reinforcement of CR in the education system is particularly vital when it comes to improving both educational achievement and life skills of learners (Agarwal, 1992). Moreover, it is quite reasonable to state that the TEFL/TESOL practice and its product which is L2 proficiency, as an example of such an educational attainment, can be highly influenced by CR. That is why Ormerod, Fritz, and Ridgeway (1999) hold that, “Changes in educational practice … place an emphasis on creativity in task design” (p. 502). Therefore, it is no wonder to observe that studying the association between CR and language teaching/learning has been “extensive and continue to be a very major point of application of a wide range of theories of creativity” (Carter, 2004, p. 213).

This section defines and justifies each procedural step which was taken throughout different stages of this study. Accordingly, the participants, instrumentation, and procedure of the study are discussed comprehensively hereunder.

This study was conducted with 182 male and female EFL learners, between the ages of 19 and 40 (mean age = 22 years), who were selected on a cluster random sampling basis from among those who were majoring in English Translation and English Literature at Islamic Azad University at Central Tehran and Roudehen.

Order to carry through the purpose of the study, the following two instruments were utilized:

- A questionnaire of creativity developed by Zaker (2013); &

- A questionnaire of critical thinking developed by Honey (2000).

The Persian Creativity Test was utilized in this study in order to estimate the degree of creativity among the participants. This questionnaire was developed and validated by Zaker (2013) based on the Creativity Test by Abedi (2002) which is in English. Zaker (2013) provides the following sections in order to assess and appraise the validity of the instrument: a report on content validity, checking the criterion-related validity, an analysis of the internal structure of the instrument employing exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses, and a report on the reliability of the instrument including 50 items.

The 50 multiple-choice items of this test have three options ranging from least to most creative responses with a range of scores between 0-2; therefore, the scores of the Persian Creativity Test could range from 0 to 100, and the participants are allocated 50 minutes to respond to the questionnaire. According to Zaker (2013), the internal consistency of the Persian Creativity Test was estimated to be 0.85 employing Cronbach’s alpha coefficient.

The Critical Thinking Questionnaire intends to explore what a person might or might not do when thinking critically about a subject. Developed by Honey (2000), the questionnaire aims at evaluating the three main skills of comprehension, analysis, and evaluation of the participants. This questionnaire is a Likert-type questionnaire with 30 items which allows researchers to investigate learners’ ability in note-taking, summarizing, questioning, paraphrasing, researching, inferencing, discussing, classifying, outlining, comparing and contrasting, distinguishing, synthesizing, and inductive and deductive reasoning.

The participants are asked to rate the frequency of each category they use on a 5-point Likert-scale, ranging from never (1 point), seldom (2 points), sometimes (3 points), often (4 points), to always (5 points); therefore, the ultimate score is computed in the possible range of 30 to150. The participants are allocated 20 minutes to complete this questionnaire. In this study the Persian version of this questionnaire which has been translated and validated by Naeini (2005) was employed. In a study conducted by Abbasi (2013) on EFL learners, the reliability of this questionnaire was estimated to be 0.79 using Cronbach’s alpha. In this study the reliability of this questionnaire was estimated to be 0.81 using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient which demonstrated a considerable degree of reliability.

To achieve the purpose of this study and address the questions posed, certain procedures were pursued which are explained below.

At the outset, all the classes in which the participants attended were codified; afterwards, one class was chosen randomly from a number of three classes available. This procedure resulted in having samples selected on a cluster sampling basis. Before administrating the questionnaires, the participants were fully briefed on the process of completing the questionnaires; this briefing was given in Persian through explaining and exemplifying the process of choosing answers. Due to the nature of correlational study, no criterion for establishing homogeneity was adopted. Moreover, the researchers intentionally randomized the order of administered questionnaires to control for the impact of order upon the completion process and validity of the data.

Thence, the two questionnaires were administrated to 300 participants. The researchers randomly observed the process of filling out for some individuals to make sure they were capable to fully understand the questions and responses. It should be added that 80 minutes were devoted to administrating these questionnaires, and attempts were made to handle the returned questionnaires and responses with confidentiality.

Subsequently, the administrated questionnaires were scored to specify the participants’ CT ability and degree of CR. From 300 participants who were given the questionnaires, 214 series of questionnaires were returned to the researchers; however, 182 series included complete responses to both of the questionnaires. Therefore, 182 sets of scores were employed to answer the questions of this study.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the relationship between EFL learners’ CR and CT. Accordingly, the researchers conducted a series of pertinent calculations and statistical routines in order to investigate the question raised and came up with certain results that are elaborated comprehensively in this part.

The data analysis provided both descriptive statistics and inferential statistics. Descriptive statistics like mean, standard deviation, and standard error of the mean were obtained. Afterwards, to check the normality of distribution, the assumptions of linear correlation were checked. Considering the inferential statistics, since the distribution of the variables was normal, Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficient was run. Moreover, the reliability of the research instruments was estimated through Cronbach’s alpha coefficient.

To run correlation the following assumptions should be checked:

- Linear relation between each pair of variables

- Normality of the distribution of the variables

- Homoscedasticity

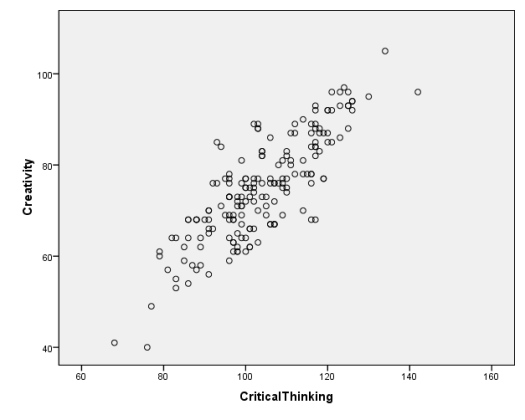

To check the linearity of the relation, a scattergram was created which is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Scattergram Showing the Correlation between CT and CR

The inspection of Figure 1 shows that the existing relationship between the scores on CR and CT is not non-linear, such as U-shaped or curvilinear distribution. Therefore, the assumption of linear relation was met.

To check the normality of the distributions, the descriptive statistics of the data were obtained which are demonstrated in Table 1.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics of the Data

| No. | Mean | Std. error mean | Sd | Skewness | Std. Error Skwnss | Skwns Ratio | Kurtosis | Std. Error Kurtss | Kurtss Ratio |

| Creativity | 182 | 74.85 | .845 | 11.393 | -.053 | .180 | -0.29 | -.035 | .358 | -0.09 |

| CriticalThin. | 182 | 103.91 | .934 | 12.606 | .061 | .180 | 0.34 | -.127 | .358 | -0.35 |

As demonstrated in Table 1, the distribution of data for CR and CT came out to be normal as both skewness ratios (-0.29 for CR and 0.34 for CT) and kurtosis ratios (-0.09 for CR and -0.35 for CT) fell within the range of -1.96 and +1.96. Therefore, the assumption of linear correlation was met. However, in order to perfectly legitimize employing the parametric technique, the following assumption had to be met.

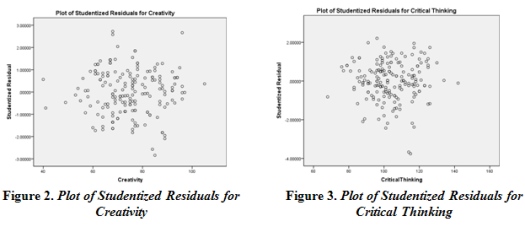

To check the assumption of homoscedasticity, the residual plots (Figure 2 and 3) were examined.

As demonstrated by Figure 2 and Figure 3, the cloud of data is scattered randomly across each plot, and thus the variance is homogenous for each variable.

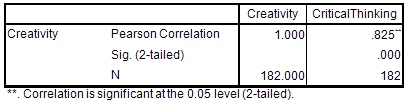

Since the assumptions of linear correlation and normality were observed for CR and CT, it was justified to employ Pearson’s product-moment formula to compute the degree of relationship between the variables. The outcome of this analysis is demonstrated in Table 2.

Table 2. Pearson Correlation between Creativity and Critical Thinking

As demonstrated in Table 2, the correlation came out to be significant at 0.05 level (r = 0.825, p < 0.05). This was supplemented by a very small 95% confidence interval (0.77-0.86). Higher power in a study will result in smaller confidence intervals and more precision in estimating correlation. Therefore, it was concluded that there is a significant and positive relationship between EFL learners’ CR and CT.

The current study attempted to investigate the possible relationship between EFL learners’ CR and CT. Based on the pertinent data analyses carried out, the researchers observed a significant and positive relationship between EFL learners’ CR and CT (r = 0.825) which indicated that CR and CT as two principal metacognitive and mental factors are closely related. Put simplistically, the results revealed that when there is variance in any of the observed variables, namely, CR and CT, there also exists variance in the other variable. This finding was indirectly supported by previous research where it was reported that both CR and CT significantly intensify and contribute to the quality of mental processes and, as a result, the quality and extent of learning (Agarwal, 1992; Chamot, 1995; Chapple & Curtis, 2000; Craft, Jeffrey, & Leibling, 2001; Halpern, 1996, 1998; Kabilan, 2000; Ku, 2009; Scriven & Paul, 2004; Wagner, 1997).

The relationship between CT and language learning as well as the relationship between CT and other related variables has been widely under investigation (Connolly, 2000; Cosgrove, 2009; Davidson, 1994; Fahim & Sheikhy, 2011; Halpern, 1998; Ku, 2009; Nosratinia & Zaker, 2013; Radhakrishnan, 2009). Similarly, the same progress has been made regarding CR (Agrawal, 1992; Carter, 2004; Craft, 2002; Lubart & Guignard, 2004; Marashi & Dadari, 2012; Ottó, 1998; Sarsani, 2006; VanTassel-Baska, 2006). However, no previous attempt was carried out to systematically investigate the relationship between CT and CR in such a context; therefore, the findings of this study could not be investigated vis-à-vis the other similar studies with the same focus.

The findings of this study have implications for EFL teachers, encouraging them to familiarize the learners with the fundamental principles of CR and CT, i.e., those of CR (fluency, flexibility, originality, and elaboration) and CT (Identifying the problem, defining the context, enumerating choices, analyzing options, listing reasons explicitly, and self-correct). EFL teachers are suggested to inform EFL learners of the ways through which CT and CR can contribute to learning more independently, reliably, and effectively. EFL teachers are recommended to plan classroom activities while attempting to integrate CT- and CR-oriented activities into the body of classroom activities. Creating an environment in which CR and CT are valued and learners take the responsibility of their own learning seems to be a considerable step toward benefiting from the potential capacities of CR and CT toward a better learning. All in all, teachers are expected to realize their role as a contributor to the improvement of their learners’ mental capacities by exposing them to different innovative and problem solving strategies on the one hand, and by providing a way to progress gradually to be more active and responsible for their own learning, on the other hand.

Due to the fact that language learning is a multidimensional phenomenon, not only language teachers, but also language learners are required to play their role properly in order to facilitate and optimize this complicated process. Therefore, results of the current study have implications for language learners, encouraging them to become more creative and critical about their learning activities. It is hoped that the results of this study would make EFL learners more internally motivated to value higher-level cognition and mental processing, especially creative and critical thinking.

Given the content of EFL/ESL materials, in present era and influenced by the heightened degree knowledge in TEFL, the language learners are also becoming the focus of curricula design (Kumaravadivelu, 2008, 2012; Nation and Macalister, 2010). This way, the results of this study would provide the evidence needed for syllabus designers and curriculum developers for integrating both CR and CT into the body of EFL materials in a way which serves the purpose of instruction and teaching best. Moreover, possessing a higher degree of understanding regarding these metacognitive variables (CR & CT) would enable syllabus designers and curriculum developers to proffer the learners the capability to know how to learn a language, how to monitor themselves, and how to develop their learning , so that they can become effective and independent language learners (Nation & Macalister, ibid). Ultimately, it is suggested to include CR and CT in the body of achievement, diagnostic, and prognostic tests of English courses.

Following the findings of this study, the subsequent recommendations are presented for further investigation hoping that other researchers would find them interesting enough to pursue in the future:

- Considering the inherent lack of control or knowledge regarding the influential factors in correlational research (Best & Kahn, 2006; Springer, 2010), it is suggested to inspect the way other mental and personality factors interact with the variables of this study.

- The same study could be conducted among other age groups.

- This study can be replicated employing some qualitative instruments e.g. interviews, diaries, and learning journals.

- It is suggested to replicate this study in a way that the numbers of male and female participants are equal. Therefore, gender might not act as an intervening variable.

Abbasi, M. (2013). The relationship among critical thinking, autonomy, and choice of vocabulary learning strategies (Unpublished master’s thesis). Islamic Azad University at Central Tehran, Iran.

Abedi, J. (2002). A latent-variable modeling approach to assessing reliability and validity of a creativity instrument. Creativity Research Journal, 14 (2), 267-276. doi: 0.1207/S15326934CRJ1402_12

Agrawal, K, P. (1992). Development of creativity in Indian schools: Some related issues. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company.

Albert, A., & Kormos, J. (2011). Creativity and narrative task performance: An exploratory study. Language Learning, 61, 73-99.

Astleitner, H. (2002). Teaching critical thinking online. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 29 (2), 53-77.

Benson, P. (2003). Learner autonomy in the classroom. In D. Nunan (Ed.), Practical English language teaching (pp. 289-308). New York: McGraw Hill.

Best, J. W., & Kahn, J. V. (2006). Research in education (10th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson Education, Inc.

Carter, R. (2004). Language and creativity: The art of common talk. New York: Routledge.

Chamot, A. (1995). Creating a community of thinkers in the ESL/EFL classroom. TESOL Matters, 5 (5), 1-16.

Chapple, L., & Curtis, A. (2000). Content-based instruction in Hong Kong: Student responses to film. System, 28 (3), 419-433.

Connolly, M. (2000). What we think we know about critical thinking. CELE Journal, 8, Retrieved April 20, 2003, from

www.asia-u.ac.jp/english/cele/articles/Connolly_Critical-Thinking.htm

Cosgrove, R. (2009). Critical thinking in the Oxford tutorial. Trinity Term: University of Oxford.

Craft, A. (2002). Creativity and early years education: A life wide foundation. London: Continuum.

Davidson, B. (1994). Critical thinking: A perspective and prescriptions for language teachers. The Language Teacher, 18 (4), 20-26.

Davidson, B. (1998). A case for critical thinking in the English language classroom. TESOL Quarterly, 32 (1), 119-123.

Davidson, B., & Dunham, R. (1997). Assessing EFL student progress in critical thinking with the Ennis-Weir Critical Thinking Essay Test. JALT Journal, 19 (1), 43-57.

Dickinson, L. (1992). Learner autonomy: Learner training for language learning. Dublin: Authentik.

Fahim, M. & Sheikhy Behdani, R. (2011). Critical thinking ability and autonomy of Iranian EFL learners. American Journal of Scientific Research, 29, 59-72.

Halpern, D. A. (1998). Teaching for critical thinking: Helping college students develop the skills and dispositions of a critical thinker. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 80, 69-74.

Halpern , D. F. (1996). Thought and knowledge: An introduction to critical thinking (3rd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Holec, H. (1981). Autonomy and foreign language learning. Oxford: Pergamon.

Honey, P. (2000). Critical Thinking questionnaire. Retrieved October 8, 2009, from Peter Honey Learning Website:

www.Peter Honey Publications.com

Jeffrey, B., & Craft, A. (2001). Introduction: The universalization of creativity. In A. Craft, B. Jefferey, & M. Leibling (Eds.), Creativity in education (pp. 1-16). London: Continuum.

Kabilan, M. K. (2000). Creative and critical thinking in language classrooms. The Internet TESL Journal, 6 (6). Retrieved November 21, 2005 from

http://itselj.org/Techniques/Kabilian- CriticalThinking.html

Ku, Y. L. K. (2009). Assessing students’ critical thinking performance: Urging for measurements using multi-response format. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 4(1), 70-76.

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2008). Understanding language teaching: From method to postmethod. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2012). Language teacher education for a global society: A modular model for knowing, analyzing, recognizing, doing, and seeing. New York: Routledge.

Lightbown, P., & Spada, N. (2006). How languages are learned (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lubart, T. I. (1999). Componential models. In M. A. Runco & S. R. Pritzker (Eds.), Encyclopedia of creativity: Volume 1 (pp.295-300). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Lubart, T., & Guignard, J. H. (2004). The generality–specificity of creativity: A multivariate approach. In R. J. Sternberg, E. L. Grigorenko, & J. L. Singer (Eds.), Creativity: From potential to realization (pp. 43-56). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Marashi, H., & Dadari, L. (2012). The impact of using task-based writing on EFL learners’ writing performance and creativity. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 2 (12), 2500-2507.

Naeini, J. (2005). The effects of collaborative learning on critical thinking of Iranian EFL learners (Unpublished master’s thesis). Islamic Azad University at Central Tehran, Iran.

Nation, I. S. P., & Macalister, J. (2010). Language Curriculum Design. New York: Routledge.

Nosratinia, M., & Zaker, A. (2013, August). Autonomous learning and critical thinking: Inspecting the association among EFL learners. Paper presented at the First National Conference on Teaching English, Literature, and Translation, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran. Retrieved from http://www.civilica.com/Paper-TELT01-TELT01_226.html

Ormerod, T. C., Fritz, C. O., & Ridgeway, J. (1999). From deep to superficial categorization with increasing expertise, In M. Hahn & S. Stones (Eds.). Proceedings of the twenty-first annual conference of the cognitive science society (pp. 502-506). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Ottó, I., (1998). The relationship between individual differences in learner creativity and language learning success, TESOL Quarterly, 32 (4), 763-773.

Radhakrishnan, C. (2009). Critical thinking and practical strategies to promote it in classroom. Retrieved September 23, 2010 from

http://chettourhorizonsforteaching.blogspot.com/2009/03/critical-thinking-practicalstrategies.Html

Rao, D. B., & Prasad, S. S. (2009). Creative thinking of school students. New Delhi: Discovery Publishing House.

Russ, S. W., & Fiorelli, J. A. (2010). Developmental approaches to creativity. In J. C. Kaufman & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of creativity (pp. 233-249). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Sarsani, M. R. (2005). Creativity: Definition and approaches. In M. R. Sarsani (Ed.), Creativity ineducation (pp. 1-7). New Delhi: Sarup& Sons.

Sarsani, M. R. (2006). Creativity in schools. New Delhi: Sarup & Sons.

Scriven, M., & Paul, R. (2004). Defining critical thinking. Retrieved January 25, 2013 from:

www.criticalthinking.org/pages/defining-critical-thinking/410

Springer, K. (2010). Educational research: A contextual approach. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Sternberg, R. J. (2009). Domain-generality versus domain-specificity of creativity. In P. Meusburger, J. Funke, & E. Wunder (Eds.), Milieus of creativity: An interdisciplinary approach to spatiality of creativity (pp. 25-38). Dordrecht: Springer.

VanTassel-Baska, J. (2006). Higher level thinking in gifted education. In J. C. Kaufman & J. Baer (Eds.), Creativity and reason in cognitive development (pp. 297-315). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wagner, R. K. (1997). Intelligence, training, and employment. American Psychologist, 52 (10), 1059–1069.

Willingham, D, T. (2008). Critical thinking: Why is it so hard to teach? Arts Education Policy Review, 109 (4), 21-29.

Zaker, A. (2013). The relationship among EFL learners’ creativity and autonomy (Unpublished master’s thesis). Islamic Azad University at Central Tehran, Iran.

Please check the Creative Methodology for the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Effective Thinking Skills for the English Language Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the How the Motivate your Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the How to be a Teacher Trainer course at Pilgrims website.

|