Application of Self-regulation in Reading Comprehension

Mahshad Tasnimi and Parviz Maftoon, Iran

Mahshad Tasnimi, PhD, is an assistant professor of TEFL at the English department of Islamic Azad University, Qazvin Branch, Tehran, Iran. She is interested in second language acquisition, language teaching methodology and testing. E-mail: mtasnimi@yahoo.com

Parviz Maftoon, PhD, is an associate professor of TEFL at the English department of Islamic Azad University, Science and Research Branch, Tehran, Iran. His primary research interests concern EFL writing, second language acquisition, SL/FL language teaching methodology, and language syllabus design. E-mail: pmaftoon@gmail.com

Menu

Introduction

Philosophical foundation of self-regulation

Self-regulated learning

Models of self-regulated learning

Applications of self-regulation in teaching reading

References

Appendix

Over the past thirty years, the concept of learning strategy has been influential in language learning and teaching. Generally, it is believed that learners with strategic knowledge of language learning become more efficient and flexible; thus they can learn a language more easily. However, learning strategies are not theoretically and operationally well-defined. Theoretically, various terminologies and classifications have been used to refer to learning strategies (O’mally & Chamot, 1990). Operationally, the psychometric properties of the assessment instruments measuring learning strategies are in question (Dornyei, 2005; Ellis, 1997; Tseng, Dornyei & Schmitt, 2006).

To overcome some weaknesses, scholars turned to a related concept, self-regulation. However, according to Dornyei (2005), this does not mean that scholars have developed second thoughts about the benefits of language learning strategies. The effectiveness of one’s own learning is seen as more important than ever before. Self-regulation, according to Dornyei offers “a broader perspective than the previous focus on learning strategies” (p. 190). That is, there is a shift from “the product (strategies) to the process (self-regulation)” (p. 191). In addition self-regulation is a more dynamic concept than learning strategy. This article intends to elaborate on the philosophical foundation, models, and strategies of self-regulation, along with the contribution of self-regulation to instruction, especially teaching reading. In this regard, some self-regulation reading tasks will be suggested.

Since 1980s, the notion of self-regulation has been applied to academic learning, and it has been investigated through different theoretical perspectives; however, self-regulated learning from social cognitive learning perspective offers a more inclusive explanation of the concept (Ping, 2012).

From social cognitive learning perspective, human learning and development are not monolithic processes. Such processes undergo different patterns of change. Social cognitive learning perspective, in general, and Bandura’s (1989) social cognitive theory (SCT), in particular, is concerned with changes in psychosocial functioning of individuals. SCT, according to Bandura, demonstrates a model of causation involving reciprocal interaction between personal, behavioral, and environmental influences.

Bandura’s theory is mainly social constructivist. According to Simon (1999), Bandura’s ideology changed from neo-behaviorism over time and emphasized the primary importance of the individual in the learning process. Simon compares five principles of constructivism which are in common with SCT.

First, a key principle of constructivism is that meaning is actively constructed by learners and that people are aware of the mismatches between their current knowledge and the new information. Likewise, SCT believes that individuals actively extract relevant information from their environment to learn and develop, and this construction of meaning is an ongoing process.

Second, another tenet of constructivism is that learning and development are social activities, enhanced with the assistance of others. In the same line, SCT is based on triadic reciprocality in which personal, behavioral, and environmental influences continually affect one another.

Third, another critical principle of constructivism is that self-regulation plays an important role in learning and development. This concept also plays a crucial role in SCT.

Fourth, the role of mental operations and formalized thought is another tenet of constructivism, which is a major concern in SCT too. According to this principle, individuals are capable of abstract thought and scientific reasoning, and they can determine which information or abilities are missing from their current knowledge.

Finally, both constructivism and SCT believe that since individuals lead different lives, reality is a personal interpretation and depends on the individuals’ perceptions of their experiences. In other words, people’s interpretations of truth and reality are not independent of their actual surroundings and are linked to their beliefs and previous experiences.

The underlying framework of the present study is social constructivism. However, as Jordan (2004) states, there are different views about what constructivism and its implications are even among constructivists themselves. All in all, this school of thought emphasizes learners’ active participation in constructing their own knowledge. Therefore, knowledge and truth are created, not discovered. Constructivism is based on interaction, in general, but social constructivism, in particular, sees “knowledge solely the product of social processes of communication and negotiation” (p. 66).

In both educational psychology and language education, extensive research effort has been made to teach learners how to learn. Since the 1970s, because of the findings in the cognitive sciences, the research concern in second language (L2) learning and teaching has shifted from methods of teaching to individual differences. Thus, investigating language learning strategies has become a featured research area in L2 studies. Comparing the research on language learning strategies in second language acquisition and self-regulated learning in educational psychology, scholars have suggested that further research in language study can be enriched through self-regulated learning (Dornyei, 2005; Ping, 2012).

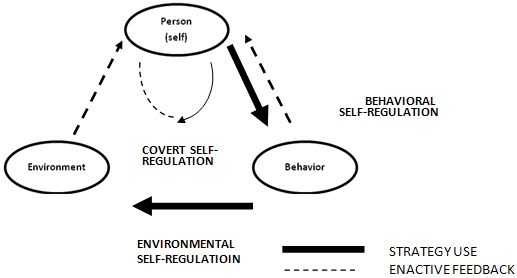

According to SCT, self-regulation is not only determined by personal processes, but also influenced by environmental and behavioral factors in mutual ways. Based on the social cognitive learning theory, Zimmerman (1989) defines self-regulation as the degree to which learners are “metacognitively, motivationally, and behaviorally active participants in their own learning process” (p.1). Zimmerman adds that this definition implies reciprocal relationship among three processes of personal, behavioral, and environmental (see Figure 1). Therefore, developing strategies to control the person, behavior, and environment help learners to be self-regulated in learning. In what follows self-regulated functioning is elaborated in terms of three areas of personal, behavioral, and environmental.

Figure 1 A triadic analysis of self-regulated functioning (Zimmerman, 1989, p. 3)

Personal influences: There are four personal influences: learners’ knowledge, metacognitive processes, goals, and affect. As far as learners’ knowledge is concerned, a distinction is made between three types of knowledge: declarative, procedural, and conditional. Declarative knowledge refers to knowledge about specific learning strategies. Procedural knowledge is knowledge of how to use these strategies, and conditional knowledge is the knowledge of when and why strategies are effective.

To Zimmerman, metacognitive decision-making processes involve two levels of planning and controlling. At a general level of self-regulation, planning involves decisional processes for selecting or changing self-regulation strategies. At a specific level, control processes guide monitoring of strategic and nonstrategic responses. According to this analysis, “students’ effectiveness in planning and controlling their use of personal, behavioral and environmental strategies to learn is one of the most visible signs of their degree of self-regulation” (p. 6)

Taking the concept of goals into account, Zimmerman states that goals should be set on the basis of their proximity in time, and it refers to as proximal goal setting. Paris and Winogard (2010) assert that when goals are set by others, behavior is obedient rather than self-directed. They point out the differences between proximal vs. distal goals, attainable vs. unattainable goals, and performance vs. mastery goals.

Affective states can also influence self-regulated learning. Zimmerman claims that evidence shows anxiety can, for example, impede different metacognitive processes, particularly control processes, and this, in turn, can inhibit setting long-term goals. He further adds that to social cognitive theorists, self-efficacy belief is a key variable affecting self-regulating learning because it is related to two key factors of learning strategy use and self-monitoring. Self-efficacy relates to a learner’s beliefs about his or her capabilities to learn or to perform a task.

Behavioral influences: According to Zimmerman (1989), there are three classes of student behavioral responses which are of relevance to the analysis of self-regulated learning: self-observation, self-judgment, and self-reaction. Each of these classes is influenced by personal processes, as well as environmental processes. In addition, the actions in these classes are observable, teachable, and interactive.

Self-observation refers to systematically monitoring one’s own performance. “Observing oneself can provide information about how well one is progressing toward one’s goals” (Zimmerman, p. 7). Zimmerman adds that two common behavioral methods of self-observation are reporting and recording of one’s actions and reactions.

Self-judgment refers to learners’ “responses that involve systematically comparing their performance with a standard or goal” (p. 7). Standards or goals may include social norms or temporal criteria, such as earlier performance on tests. Two common ways of self-judgment are checking and rating. Re-examining one’s answers to a leaning problem and rating one’s answer in relation to those of others or an answer sheet are two examples of checking and rating procedures respectively.

The third class of student self-regulated response is self-reaction to one’s performance. Zimmerman enumerates three interdependent classes of self-reaction strategies, derived from SCT. The first one is behavioral self-reaction strategies by which learners try to optimize their learning responses. Using such strategies as self-praise or self-criticism is a case in point. The second class of reaction strategies is personal by which learners seek to enhance their personal processes, such as goal setting or memorizing. Environmental self-reaction strategies are the third class by which learners try to improve their learning environment. Structuring one’s own environment and asking for help are, according to Zimmerman, two common environmental self-reaction strategies.

Environmental influences: Social cognitive theorists have paid particular attention to the impact of social experience and environment on human functioning and learning. Zimmerman mentions five environmental influences which are assumed to be reciprocally interactive with personal and behavioral influences. Modeling is one type of environmental influences, which are given particular emphasis in SCT, and has effect on self-regulation. Modeling of affective coping strategies is an example in this regard. According to SCT, verbal persuasion is another important form of environmental influences; however, Zimmerman states that this type of social experience is less effective because it depends on learners’ level of verbal comprehension, but if combined with other forms of environmental experiences, it can be a powerful medium for conveying a wide variety of skills. Verbal elaboration of a manipulation sequence is an example of verbal persuasion. Direct assistance from others, like seeking help from teachers regarding an assignment, and using symbolic forms of information, such as pictures, diagrams, and formulas are two other sources of social support. The final type of environmental influence is the structure of the learning context. According to SCT, learning is highly dependent on the context, such as task or setting. Changing the difficulty level of a task or changing a noisy academic setting for a quiet one are two cases in point.

Various models have been proposed for self-regulated learning. According to Pintrich (2004), there are four assumptions underlying most self-regulated learning models. The first assumption is the active, constructive assumption, which views learners as active participants in their learning process, constructing their own meanings, goals, and strategies from the information in the external environment, as well as information in their own mind. The second assumption is the potential for control assumption, assuming that learners can potentially monitor, control, and regulate some aspects of their cognition, motivation, and behavior, as well as some features of their environments; however, there are some biological, developmental, contextual, and individual differences constraints. The third assumption is the goal, criterion, or standard assumption, stating that learners set some type of learning standards or goals to assess their learning process to see if they should continue or some change is necessary. The fourth assumption is that self-regulatory activities are mediators between personal and contextual characteristics and actual achievement or performance. That is, the individuals’ self-regulation of their own cognition, motivation, and behavior mediate the relations between the person, context, and final achievement.

Two mostly-referred models of self-regulated learning are those of Zimmerman (2002) and Pintrich (2004). These models are explained below.

The Zimmerman model

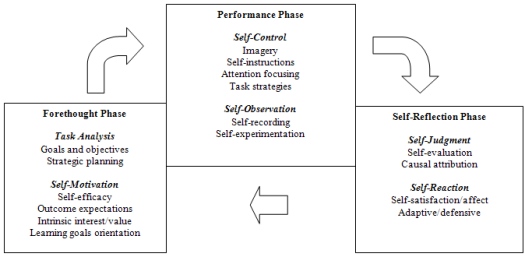

Zimmerman (2002) states that self-regulated learning is not “an academic performance skill; rather it is the self-directive process by which learners transform their mental abilities into academic skills” (p. 65). He describes self-regulated learning as an open and cyclical process on the part of the learner that occurs in three main phases: forethought, performance, and self-reflection. Each phase is divided into subcategories. As seen in Figure 2, the forethought phase is the planning phase which precedes learning. Two major classes of forethought processes are task analysis and self-motivation. Task analysis involves goal setting and strategic planning. Taking a spelling test into account as an example, a learner may select a goal of memorizing a word list and plan to use spelling strategies, such as dividing words into syllables. Self-motivation originates from the learners’ beliefs about themselves, as well as the learning process. For example, being self-efficacious or intrinsically motivated enhances learning.

Figure 2 The Zimmerman model’s of self-regulated learning cycle (Zimmerman, 2002, p. 67)

The second phase is the performance phase during which learners employ a variety of strategies, which help them maximize their academic performance. This phase involves two main classes of self-control and self-observation. Self-control refers to employing the strategies, selected during the forethought phase. Forming an image to memorize a new word or locating one’s place of study away from distracting noises are two examples of self-control methods. Self-observation refers to self-recording, such as self-recording one’s time to be aware of how much time one has spent learning.

In the third phase, self-reflection, judgments are made about one’s actions. Self-judgment and self-reaction are two major classes of this phase. One form of self-judgment is self-evaluation, which refers to comparing one’s performance against some standard. The standard could be one’s prior performance, another person’s performance, or an absolute standard. Another form of self-judgment is causal attribution, referring to beliefs about the cause of one’s failure or success. Self-reaction also takes different forms. For instance, self-satisfaction, which enhances motivation, is a case in point. Defensive reactions and adaptive reactions are two other forms of self-reaction. The former refers to efforts to protect one’s self-image, while the latter refers to adjusting one’s performance to increase learning. Being absent from a test and discarding an ineffective learning strategy are two examples of defensive and adaptive reactions, respectively.

As mentioned earlier, these phases are considered cyclical. The forethought phase prepares the student for learning and influences the performance phase. This, in turn, affects the processes of the self-reflection phase, which interact with the next forethought phase. Each phase can facilitate or hinder the subsequent phase of the cycle.

The Pintrich model

This model is also based on a socio-cognitive perspective. There are four regulatory phases in this model: planning, self-monitoring, control, and evaluation. Within each phase, self-regulation activities are structured into four areas: cognitive, motivational/affective, behavioral, and contextual (Pintrich, 2004). Table 1 displays Pintrich conceptual framework.

Pintrich states that the four phases that make up the rows of the table reflect the processes that the models of self-regulation share (e.g., Zimmerman’s model) and reflect goal-setting, monitoring, control, and regulation processes.

The first phase involves planning and goal-setting. It also includes knowledge activation of the task, context, and the self in relation to the task. The second phase represents different monitoring processes that concern mainly metacognitive awareness. In this phase, there are activities that help learners become aware of their own self, task, and context. The third phase concerns control and regulation of different aspects of the self, task, and context. Finally, the last phase shows different kinds of reactions and reflections on the self, task, and context. Pintrich adds that these phases are not hierarchically or linearly structured. They can occur simultaneously and dynamically.

The columns of Table 1 represent the four areas of self-regulation within each phase. The activities are structured based on these areas--cognition, motivation and affect, behavior, and context.

Table 1

The Pintrich Model’s of Self-regulated Learning (Pintrich, 2004, p. 390)

| Areas for regulation |

| Phases and relevant scales |

Cognition |

Motivation/Affect |

Behavior |

Context |

Phase 1

Forethought, planning,

and activation

|

Target goal setting

Prior content knowledge

activation

Metacognitive knowledge

activation

|

Goal orientation adoption

Efficacy judgments

Perceptions of task

Difficulty

Task value activation

Interest activation

|

Time and effort planning

Planning for

self-observations of behavior

|

Perceptions of task

Perceptions of context

|

| Phase 2

Monitoring

|

Metacognitive awareness

and monitoring of

cognition

|

Awareness and

monitoring of

motivation and affect

|

Awareness and

monitoring of effort,

time use, need for help

Self-observation of

behavior

|

Monitoring changing task and context conditions |

| Phase 3

Control

|

Selection and adaptation

of cognitive strategies

for learning, thinking

|

Selection and adaptation

of strategies for

managing, motivation,

and affect

|

Increase/decrease effort

Persist, give up

Help-seeking behavior

|

Change or renegotiate

task

Change or leave context

|

| Phase 4

Reaction and

reflection

|

Cognitive judgments |

Affective reactions

Attributions

|

Choice behavior

Attributions

|

Evaluation of task

Evaluation of context

|

In sum, comparing the two models, both share the same underlying foundation, looking at self-regulated learning as a cyclic, dynamic, and constructive process where learners set goals for their own learning and make an effort to control and regulate their performances, and then evaluate and reflect on the regulated learning processes.

Different studies have investigated the role of self-regulated strategies and language learning and found a positive relationship between application of self-regulated learning strategies and success in language learning (Abrami et al., 2010; Mirhassani, Akbari, & Dehghan, 2007; Orhan, 2007; Sanz De Acedo & Iriarte, 2001; Tseng, Dornyei, & Schmitt, 2006). Research has also revealed that self-regulation facilitates reading comprehension in particular (McMahon & Dunbar, 2010; Nash-Ditzel, 2010; Swalander & Taube, 2007; Tasnimi, 2013).

According to Nash-Ditzel’s (2010) study, teaching techniques based on self-regulation and reading strategies could significantly promote improved reading abilities in college students. Using interviews think-aloud protocols, informal observations, and document analysis, Nash-Ditzel found that the knowledge and ability to use reading strategies contributed to the students' ability to self-regulate while reading.

McMahon and Dunbar (2010) showed that empowering learners through self-regulated online learning, rather than traditional learning approach, based on knowledge transfer, develops students’ independent skills in reading and understanding academic texts. In their study, the participants used the online environment to promote their reading comprehension through a process of scaffolded reciprocal teaching.

Swalander and Taube (2007) also investigated the effect of self-regulated learning on reading comprehension. The results showed that family-based prerequisites, academic self-concept, and reading attitude significantly influenced reading comprehension. Academic self-concept showed a direct and strong influence on goal-oriented strategies and on reading comprehension in the eighth grade Swedish students.

In Tasnimi’s (2013) study, the concept of self-regulation was narrowed down to eight categories of strategies in reading. The strategies were based on Zimmerman’s self-regulation strategies, tapping three areas of personal, behavioral, and environmental influences. The participants in the self-regulated groups received explicit teaching of self-regulation strategies through the instructor’s explanation, along with task-supported teaching; the participants applied what they had been taught on different reading texts in task-supported formats. The findings showed that self-regulated learning had a significant effect on EFL learners’ reading comprehension and reading fluency.

Since self-regulation facilitates reading comprehension (McMahon & Dunbar, 2010; Nash-Ditzel, 2010; Swalander & Taube, 2007; Tasnimi, 2013), it has implications for the ways teachers should interact with students. Learners do not get self-regulated automatically, and self-regulated ability does not develop with age (Lapan, 2008; Orhan, 2007). On the other hand, self-regulated learning is teachable and can lead to increase in students’ achievement (Abrami et al., 2010; Mirhassani, Akbari, & Dehghan, 2007; Orhan, 2007; Sanz De Acedo & Iriarte, 2001; Tseng, Dornyei, & Schmitt, 2006). Therefore, learners should be given choices to practice self-regulation in reading classes both directly and indirectly through carrying out related tasks or activities. The following are some general guidelines for enhancing self-regulation in reading suggested by different scholars, such as Torrano and Torres (2004), and Lapan (2008).

- Direct teaching: Self-regulation can be taught directly by explaining the strategies that can help or hinder the learning process.

- Modeling: Modeling is an indirect way of teaching self-regulation, in which learners observe the teacher performing self-regulation strategies.

- Practice: Practicing overt and covert strategies can be done through a variety of learning tasks. It can be done first guided and then independently. Overt strategies are those that can be seen, such as underlying and note taking, while covert strategies are referred to as internal mental processes, such as imagery or relating new information to prior knowledge.

- Self monitoring: Learners can self-monitor themselves by making use of internal and external factors, on the one hand, and setting short term realistic and specific goals, on the other hand.

- Self-evaluating: Evaluating their own performance, learners will understand the benefits of self-regulated learning. In this regard, Paris and Winogard (2010) state that teachers can help learners to think of failure as a constructive process. That is, teachers should help students realize how to respond to the failure, and that the failure itself does not matter. Analyzing the reasons behind the failure can help learners to revise their approach to learning, and start over with better plans.

Self-regulation is a feasible and practical teaching method that helps learners to see themselves as agents of their own learning and to get involved in an active constructive reading process. Furthermore, self-regulation is a cost-effective teaching method with characteristics compatible with the current wave of educational reform, such as accounting for learners’ needs and goals, allowing student creativity and innovation, and enhancing learners’ sense of self-worth. Self-regulation does not only enhance learners’ reading comprehension, but it also helps learners to transform their mental abilities into academic skills.

Task-supported teaching can be selected as a means of instruction because it teaches learners how to proceduralize strategic solutions to problems (Skehan, 1996). Equally important, task-supported instruction has strong empirical evidence (Nunan, 1991). Furthermore, it focuses on meaning, real world relationship, and outcome (Prabhu, 1987, Skehan, 1996) which are of interest in self-regulation.

In this regard, the researchers have designed reading tasks based on self-regulation strategies proposed by Zimmerman (1989) (see Table 2). The strategies included in eight categories, which have to be carried out successively (see Appendix):

- Environmental Structuring

- Organizing and Transforming

- Goal Setting and Planning

- Keeping Records and Monitoring + Organizing and Transforming

- Seeking Information + Seeking Social Assistance

- Rehearsing and Memorizing

- Reviewing Records

- Self-evaluation + Self-consequating

The tasks in the environmental structuring category require the learners to pay attention to the environment, and to find distractions, such as air conditioner and their classmates’ whispering. Then they have to write if they can adjust the situation for better results, or they should tolerate the distractors. Organizing and transforming tasks, however, help the learners to take a quick look at the text before reading to see how the text is organized in terms of title, heading, sub-heading, and paragraphs. The tasks in the goal setting and planning category get learners to guess how much time they need to read the text and do the activities. Therefore, they learn to budget their time in advance. The tasks in the next category focus on keeping records and monitoring, as well as organizing and transforming strategies. Here, the learners are required to read the text paragraph by paragraph, draw an outline, and highlight the ambiguous words, phrases, or sentences for further investigation. The tasks in the fifth category assist the readers to seek information and social assistance. To do so, they specify which ways they would like to use to remove the ambiguities they have encountered in the previous phase. Rehearsing and memorizing tasks draw learners’ attention to the strategies that help them to memorize unfamiliar words. Hence, they are required to check the strategies that seem most useful to them. Tasks related to reviewing record strategy ask learners to go back to the previous phases and check if they have taken all the steps to remove unclear points before going to the next phase. Finally, there are self-evaluation and self-consequating tasks that require learners to self-evaluate themselves by answering some questions about their performance, such as how they score themselves and how they have done the tasks.

Table 2

Self-regulated Learning Strategies (Adapted from Zimmerman, 1989 & NRC/GT, 2011)

| Category definitions |

Substrategies |

A. Personal. These strategies usually involve how a student organizes and interprets information and include:

- Organizing and transforming: Self-initiated overt or covert rearrangement of instructional materials to improve learning.

|

Outlining

Summarizing

Rearrangement of materials

Highlighting

Drawing pictures, diagrams, or charts

Using flashcards or index cards

Using concept webs and mapping

|

- Goal-setting and planning: Setting educational goals or subgoals and planning for sequencing, timing, and completing activities related to the self-set goals.

|

Sequencing

Timing

Time management

Pacing

|

- Keeping records and monitoring: Self-initiated efforts to record events or results.

|

Note-taking

Listing errors made

Recording grades

Maintaining a portfolio

keeping all drafts of assignments

|

- Rehearsing and memorizing: Self-initiated efforts to memorize learning materials by overt or covert practice.

|

Using mnemonic devices, mental imagery, or repetition

Teaching someone else the material

Making questions

|

- Rehearsing and memorizing: Self-initiated efforts to memorize learning materials by overt or covert practice.

|

Using mnemonic devices, mental imagery, or repetition

Teaching someone else the material

Making questions

|

| B. Behavioral: These strategies involve actions that the student takes and include:

Self-initiated evaluations of the quality or progress of learners’ work.

|

Analyzing the task

Reflecting on self-instruction, feedback, and attentiveness

|

C. Environmental: These strategies involve seeking assistance and structuring of the physical study environment and include:

- Seeking information: Self-initiated efforts to secure further task information from nonsocial sources.

|

Using library and internet resources |

- Environmental structuring: Self-initiated efforts to select or arrange the physical setting to make learning easier.

|

Selecting or arranging the physical setting

Isolating, eliminating, or minimizing distractions

Breaking up study periods and spreading them over time

|

- Seeking social assistance: Self-initiated efforts to solicit help from peers, teachers, and adults.

|

Seeking social assistance from peers, teachers, other adults

Emulating exemplary models

|

- Reviewing records: Self-initiated efforts to reread notes, tests, or textbooks to prepare for class or future testing.

|

Reviewing records

Rereading notes, tests, and textbooks

Structuring the study environment

|

An example of tasks is provided below. Taking environmental structuring strategy as an example, the learners are required to practice this strategy in the form of the following task.

Task: Environmental Structuring

Pay attention to your environment. What distracts you? How can you change the situation for the better?

| Distractions | I can adjust it by … | I should tolerate it |

| Air conditioner | | |

| People’s whispering | | |

| Noise from outside the room | | |

| Your thoughts | | |

| Others: ---------------- | | |

Since the distinction between a task and an activity is not always clear (Howatt & Widdowson, 2004), the term task and activity are used interchangeably in this paper. In addition, as Howatt and Widdowson rightly declare “the real world relationship of many of the tasks proposed in TBI [Task Based Instruction] is somewhat tenuous” (p. 367), the designed tasks differ in their amount of relationship to the real world, depending on the nature of reading texts and self-regulation strategies. In other words, in some tasks, learners should make use of their imagination to replicate the real world.

To sum up, the goal of self-regulation training, according to Zimmerman (2002), is to empower learners and allow them to take control of their learning process. In this paper, this control was narrowed down to reading comprehension in designing self-regulation reading tasks.

The implications should be addressed by educators, and the materials developers of language instructional materials, or by any well- informed teachers who recognize the difference that self-regulation can make to the process of learning. It is hoped that the argument shared in his study will inspire further research and lead to closer partnership between teachers and learners so that learners are given more choices to practice self-regulation in their studies.

Abrami, P. C., et al. (2010). Encouraging self-regulated learning through electronic portfolios.

Retrieved December 8, 2010, from

www.ccl-cca.ca

Bandura, A. (1989). Social cognitive theory. Annals of Child Development, 6, 1- 60.

Dornyei, Z. (2005). The psychology of the language learner Individual differences in second

language acquisition. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Ellis, R. (1997). Second language acquisition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Howatt, A. P. R., & Widdowson, H. G. (2004). A history of English language teaching (2nd

ed.).Oxford: OUP.

Jordan, G. (2004). Theory construction in second language acquisition. Amsterdam: John

Benjamins Publishing Company.

Lapan, R. T. (2008). Empowering students to become self-regulated learners. Retrieved

December 8, 2010, from www.sfu.ca/~sbratt/SRL/

McMahon, M., & Dunbar, A. (2010). Mark-up: Facilitating reading comprehension through on-

line collaborative annotation. Retrieved October 7, 2010, from

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download

Mirhassani, A., Akbari, R., & Dehghan, M. (2007). The relationship between Iranian EFL

learners’ goal-oriented and self-regulated learning and their language proficiency. Journal of Teaching English Language and Literature Society of Iran, 1(2), 117-132.

Nash-Ditzel, S. (2010). Metacognitive reading strategies can improve self-regulation. Journal of College Reading and Learning. Retrieved October 7, 2010, from

www.thefreelibrary.com

NRC/GT (The National Research Center on the Gifted and Talented). (2011), Self-regulation.

Retrieved January 10, 2011, from

www.gifted.uconn.edu/siegle/SelfRegulation/section0.html

Nunan, D. (1991). Communicative tasks and the language curriculum. TESOL Quarterly, 25(2),

279-295.

O’Malley, J. M., & Chamot, A. U. (1990). Learning strategies in second language acquisition.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Orhan, F. (2007). Applying self-regulated learning strategies in a blended learning instruction.

World Applied Sciences Journal, 2(4), 390- 398.

Paris, S. G., & Winograd, P. (2010). The role of self-regulated learning in contextual teaching:

Principles and practices for teacher preparation. Retrieved December 8, 2010, from

www.ciera.org/library/archive/ 2001-04/0104parwin.htm

Ping, A. M. (2012). Understanding self-regulated learning and its implications for strategy

instruction in language education. The Journal of Language Teaching and Learning, 2(2), 89-104.

Pintrich, P. R. (2004). A conceptual framework for assessing motivation and self- regulated

learning in college students. Educational Psychology Review, 16(4), 385-407.

Prabhu, N. S. (1987). Second language pedagogy. Oxford: OUP.

Sanz De Acedo, M. L., & Iriarte, D. I. (2001). Enhancement of cognitive functioning and self-

regulation of learning in adolescent. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 4(1), 55-64.

Simon, S. D. (1999). From neo-behaviorism to social constructivism: The paradigmatic non-

evolution of Albert Bandura. Unpublished Bachelor’s thesis, Emory University, Atlanta, USA.

Skehan, P. (1996). A framework for implementation of task-based instruction. Applied

Linguistics, 17(1), 38-62.

Swalander, L., & Taube, K. (2007). Influences of family based prerequisites, reading attitude,

and self-regulation on reading ability. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 32(2), 206–230.

Tasnimi, M. (2013). Evaluating the predictive power of syntactic knowledge, vocabulary

breadth, and metacognitive strategies in reading fluency and reading comprehension in self-regulated vs. non self-regulated readers. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Islamic Azad University, Science and Research Branch, Tehran, Iran.

Torrano, F., & Torres, M. C. (2004). Self-regulated learning. Electronic Journal of Research in

Educational Psychology, 2(1), 1-34. Retrieved December 8, 2010, from

www.sfu.ca/~sbratt/

Tseng, W., Dornyei, Z., & Schmitt, N. (2006). A new approach to assessing strategic learning:

The case of self-regulation in vocabulary acquisition. Applied Linguistics, 27(1). 78-102.

Zimmerman, B. (1989). A social cognitive view of self-regulated academic learning. Journal of

Educational Psychology, 82(3), 1-23.

Zimmerman, B. J. (1990). Self-regulated learning and academic achievement: An overview.

Educational Psychology, 25(1), 3-17.

Zimmerman, B. J. (2002). Becoming a self-regulated learner: An overview. Theory into Practice,

41(2), 64-70.

Self-regulation Reading Tasks

You are going to go through some reading self-regulation phases which help you to be an active reader metacognitively, motivationally, and behaviorally. Therefore, you will be able to control yourself, your behavior and your environment better while reading.

Please fill in the charts and answer the questions as recommended below.

I Environmental Structuring

Pay attention to your environment. What distracts you? How can you change the situation for better?

| Distractions | I can adjust it by… | I should tolerate it |

| Air conditioner | | |

| People’s whispering | | |

| Noise from outside the room | | |

| Your thoughts | | |

| Others: ---------------- | | |

II Organizing and Transforming

Take a quick look at the text, and then complete the following chart.

| Questions | Answers |

| What is the title of the text? | |

| How many paragraphs are there in the text? | |

| How many headings are there in the text? | |

| How many subheadings are there in the text? | |

III Goal Setting and Planning

Before reading the text, go through the following steps:

Go over the pre-reading questions.

Guess how much time you need to read the text and do the activities:

| I guess I need --------------- minutes to go through the text and do the activities. |

IV Keeping Records and Monitoring + Organizing and Transforming

Read the text paragraph by paragraph. Please take the following steps in this phase:

If you face any ambiguous word, phrase, or sentence, take one of the following steps to highlight them for further investigation:

Annotating

Underlining them

Jotting them down on your notebook

Is there any other way you would like to use to highlight them? If yes, please specify?

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Draw an outline for the paragraph.

Write a 1-3 sentence summary, according to your outline. |

V Seeking Information + Seeking Social Assistance

Which of the following ways did you use or would you like to use to remove the ambiguities in the previous phase? Please specify them.

| Ways | I tried this way to … |

| Guessing | |

| Surfing the net | |

| Asking the teacher | |

| Asking your friends | |

| Consulting a dictionary | |

VI Rehearsing and Memorizing

Which strategy helps you most to memorize unfamiliar words? Please put a check mark on the following list (You may check more than one option).

| Strategy | |

| Writing them down | |

| Using mental imagery | |

| Using repetition | |

| Using flash cards | |

| Sticking them on the wall | |

| Learning them from the context | |

| Learning them through derivation | |

| Recording and then listening to them | |

| Learning them through synonyms or antonyms | |

VII Reviewing Records

Go back to the previous phases and check the following:

Have you taken all the steps?

Is there any unclear point? If so, remove it before going to the last phase.

VIII Self-evaluation + Self-consequating

Self-evaluate yourself by answering the following questions. Put a checkmark next to your answers.

How much did you get the text?

100% 50-100%% less than 50% |

Which phase helped you more to deal with the text?

------------------ |

Have you done the activities correctly?

All of them% Most of them% Some of them |

Was your time estimation correct?

Yes% No |

How was your performance in general?

Very well% So-so% Not satisfactory |

How do you score yourself from 1 to 20?

------------------ |

Is there anything else you would like to mention about your reading

performance? Please specify (you may specify it in Persian).

----------------------------------------- |

How do you like this way of reading a text?

Merits: -----------------------------------------

Demerits: ----------------------------------------- |

Please check the Creative Methodology for the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the How the Motivate your Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Building Positive Group Dynamics course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the How to be a Teacher Trainer course at Pilgrims website.

|