Remembering Robert O’Neill

joint article

Impossible, brilliant and a wonderfully engaging human being, Robert was a trailblazing educator to whom everybody in ELT, teachers of students alike, owes a huge debt.

Neil Butterfield

Baxter helped Coke to his feet. "What we know now already proves you were innocent," he said. Then he untied Coke's hands. Coke was a free man again.

Robert O'Neill: The Man Who Escaped Episode 24 (Final)

Menu

From Alan Maley

From Simon Greenall

From Judy Garton-Sprenger

From Tim Hunt

From John Walsh

From Roy Kingsbury

From Marion Cooper

From Judith King

From Liu Dailin

From Norman Whitney

From Brian Tomlinson

From Philip Prowse

From Jeremy Harmer

From Barry Tomalin

From Cristina Whitecross

From Judith Cunningham

From Rosalyn Hurst

From Peter Viney

The last time I saw Robert as a real person, before he was hospitalised and became someone I did not recognise, was a few months ago in Covent Garden, where we had lunch – a routine we had developed, to meet two or three times a year. As always, he had a book about his person. He was one of the most avid readers I have ever met – dauntingly well-read in fact. We consumed three bottles of wine, and he insisted on capping the occasion with cognacs. The conversation was, as always, anarchic and colourful, and interspersed with attempts to engage with the attractive Polish server, and occasional bursts of very loud German, with no regard to the fact that no Germans were at hand. In other words, typically Robert.

I met him over 40 years ago when he came to Paris to present at a Triangle event, where three languages were used without interpreters. He was perfectly at home, especially in German – and had no qualms about creatively adapting French to his own communicative purposes. Over the years, we shared platforms in places like Zaragoza, and he stayed with me in Singapore. We worked together in Japan at LIOJ summer schools for several years running in the 90’s too.

What I most remember about Robert was his sharp mind, his inexhaustible curiosity, his passion for what he did, his exacting professionalism, his integrity, his creative talent and his generosity. He was unfailingly helpful to young teachers, and gave his time and expertise unstintingly.

His contribution to our profession has been immeasurable, as a writer of materials, a charismatic presenter, and an inspirational presence. He deserves to be remembered with affection and respect. We shall not see his like again. Goodbye Robert. Vale!

I’m sure many people will talk of Robert’s contribution to ELT through his books English in Situations, Kernel Lessons, the Lost Secret and many others. Like many of my generation of teachers and writers I was in awe of his achievements.

But it was Robert’s character which I also remember. After a Longman BBC conference in 1992, in a water taxi in the middle of the Venice lagoon, with Robert holding forth, a colleague said., 'Robert, I think you invent your girlfriends just to illustrate the English tense system.' Quick as a flash, Robert said, 'Quite right. You don't love me - present simple negative, you've never loved me - present perfect, you're always cheating on me - present continuous, if you loved me, you wouldn't treat me like this … etc.' When he was funny, he was very funny.

He had serious moments too. As plenary speakers at IATEFL Hungary some time in the 90s, we were put up separately from everyone else in a very comfortable, large but rather empty guest house miles from anywhere. We spent the night sharing too much Scotch and talking … talking seriously about things. Robert’s schtick was ‘I was born in South Chicago, on the wrong side of the tracks …’ and everything he said in public and private seemed to take him back there, for better or worse. He talked about his family and his friends with love and passion, and we talked about our work and ELT and writing. It was a memorable time for me.

Robert was not afraid to be controversial… I wonder if this was because he was so honest, so straight-talking that he didn’t even acknowledge it as controversy. And because of this, many people were understandably unable to get past the highly-coloured language and fruity anecdotes he told both on- and off-stage. Professionally, he was the original Marmite man: you loathed him, or you loved him.

Personally, it was an extraordinary privilege for me to get to know him a little, not closely, but just a little behind his public persona. And for all of this, I respected him enormously and loved him just a little too.

Robert O’Neill was a pioneer in the development of ‘modern’ ELT. For teachers in 1970, before the explosion of general English course books and the dawn of the communicative approach, there were relatively few published ELT materials. Like many teachers at the time, I wrote my own. And so, for many of us, O’Neill’s English in Situations (OUP 1970) provided invaluable support in the classroom – my copy became so well worn that I had to transfer its pages to a ring-binder file. And then came Kernel Lessons Intermediate (O’Neill, Kingsbury & Yeadon; Longman 1971). This was another ground-breaker, with the added bonus of an ingenious ongoing detective story, ‘The Man Who Escaped’ (aka ‘Coke’), that delighted students and teachers alike. On first meeting Robert a few years later, I was struck that this apparently mischievous maverick had produced such meticulously structured and carefully wrought materials.

Story-telling was just one of Robert’s many talents. He was a highly entertaining – sometimes controversial – speaker, never afraid to rock the boat, and he used his experience as an actor to compelling effect in his talks. He travelled the world with a zest for learning and discovery; beneath the playful exterior was a deeply serious person of great integrity, always both interesting and interested. He was sui generis, extraordinary in the literal sense of the word. Thank you, dear Robert.

With Judith King, Senior Editor, I was the publisher in Longman of Robert's English as a Foreign Language course books in the '70s and '80s. At times you might have thought he never wanted to be an EFL author. Having been, so he said, a bit-part Shakespearian actor in the States, he may have hankered after the life of a 'real' writer. But he was a real writer in his own inimitable way. He was a one-off genius, both brilliant and exasperating. The complete structure and content of a unit came straight out of his head and into typescript, which like as not he then consigned to the bin - with cries of 'no' that's fine from his publisher and co-author. But to no avail. Naturally Robert wasn't good on deadlines, and missing them was the only thing that clouded the relationship with this wonderful but wayward man. He was great fun to be with, a splendid raconteur and a good friend.

Robert O'Neill was undoubtedly the most charismatic writer with whom I ever had the privilege of working; I was his desk editor at Longman as they published Kernel Lessons Intermediate (KLI). He was also to become a friend, and even agreed for a time to lend the use of his name as Company Secretary to BEBC.

In his public life, Robert was often outrageous, but only to stimulate a response from his audience, whether it was an individual or a group of teachers. His extraneous comments and references to bodily parts or their functions are legendary. In many ways he shared a love of language and life with the likes of Dylan Thomas and you couldn't help being drawn to him.

He always thought outside the box, long before the expression (or the box) had entered common parlance and especially when dealing with established "authority". He described working on KLI as "a glorious battle" and this was working with his publishers who, to mix metaphors, spent a lot of time trying to force Robert inside a box of theirmaking.

At a time when publishers are now seeking to re-brand authors as mere "content providers" it is particularly sad, and ironically fitting, that the ELT world has lost its most colourful and creative contributor, the like of whom we shall never see again.

In 1969 Longman published the ‘Eurocentre Internal Edition’ of an English language teaching coursebook entitled Kernel Lessons Intermediate Stage. This was followed two years later (after rigorous trialling, I remember), by an updated version entitled Kernel Lessons Intermediate, which was also published by Longman and which became one of the most popular ELT courses used at the time in colleges and private language schools across the country.

While there were three co-authors on the project as it progressed (O’Neill, Kingsbury and Yeadon), the Kernel Lessons series was Robert’s initial concept, and it was his typical insight into English and the teaching of English as a foreign language, together with his drive, that struck a chord with teachers and learners alike.

Robert O’Neill was not your average teacher or your average textbook course writer - far from it! He was ‘driven’ and constantly full of ideas. While the rest of us could agree and write to an agreed syllabus, Robert was what might be called ‘a free spirit’. He was able to engage students’ interest by employing the syllabus language in a variety of situations, and in an element of fiction - and it’s the episodic story of The Man Who Escaped that I suspect many students at that time still remember today! Students of mine certainly enjoyed learning from Kernel Lessons Intermediate, but as they worked their way through the course and acquired more English Unit by Unit, most could hardly wait to read the latest episode of the story of Edward Coke.

Another striking feature of the course (which I seem to recall was another of Robert’s ideas) was the format of Kernel Lessons Intermediate Teacher’s Book: in effect it was the Students’ Book with teacher’s notes incorporated – so easily usable in class, and an indispensable aid to any teacher.

As an EFL teacher and textbook writer, throughout his career Robert O’Neill was an innovator and an enthusiast steeped in his creative work. The world of English language teaching will be a poorer place without him!

I worked closely with Robert as his publisher at Longman, mostly on Third and Fourth Dimension. Working with him was both energising and exasperating. We had enormously creative and productive meetings (punctuated by Robert breaking off to do Tai Chi in the corner) followed by desperate late night phone calls telling me he was going to ‘throw the whole thing down the can’. Or, if he didn’t like my feedback, I would receive a long letter justifying everything he had written – and then a revised version (usually much improved).

Robert’s approach to writing ELT materials was unique. His initial focus was always on the characters and the story and only when he felt they were right would he focus on the syllabus and sequencing. As the language came to the fore, the characters and story would evolve, and completion became an ever elusive goal. Meeting publishers’ deadlines was never one of Robert’s strong points. His writing had brilliance however – no one could write exercises for beginners like Robert could – a subtle story woven into even the simplest of practice drills.

With Robert you either loved him or loathed him. At his best he was tremendously good company - warm, interested and full of ideas. His controversial opinions and stories of his amorous adventures were not to everyone’s taste however. For me they were just part of Robert. Yes, he could be shocking, and even offensive, but that was part of his eccentricity.

I was last in touch with Robert in February of this year – he wrote to ask if there was anyone at OUP who might publish his latest work on ELT. Looking back, I am reminded of the slogan on a T-shirt Longman gave him at a celebratory party - ‘Kernel authors keep it up for years!’ Robert certainly did that. He was a special person and I feel privileged to have known him.

Robert O’Neill - Albert Einstein look-alike - was predictably unpredictable. Would he smile benignly and behave, or would he rant and rave? Either way, I rather loved him for it.

I knew Robert in the late 1970s and 1980s as his editor on the Kernel series, and worked with him when he was Series Editor of Longman Structural Readers. At the many meetings we had at Longman’s Bentinck Street offices, Robert would rarely sit still. He’d pace around, arms flailing, dreaming up a new idea or despairing over the last one. I would rescue perfectly good material from the waste-paper bin.

With his lively mind, creativity and encyclopaedic knowledge, Robert brought to ELT a rich understanding of language learning and a gift for story-telling. Genuinely interested in and appreciative of his team, he was great fun to be with, and conversations with him were truly fascinating.

Robert was mischievous and loved to shock. Going through his manuscripts I had to be on the lookout for obscenities embedded in amongst a text on, say, the third conditional. You never quite knew where the shock might be lurking, and it’s a shock to me now that this great man is no more.

Robert O’Neill never visited China, but his two English language teaching courses used to be very popular in China though, unfortunately his name as the author might not be well-known. Kernel Lessons was among the few English course books used in the Chinese universities in the late seventies and early eighties in the last century. When I was amused by his wittiness as a visiting lecturer on my MA course in Britain in 1993, I introduced myself to him and told him how the Chinese students enjoyed his Kernel Lessons. He seemed to be surprised to hear what I said about his course books used in China and said he was delighted to know that, though he had not got a penny from that market. Later he told me that he had written another English language teaching course The Lost Secret which was professionally produced by the BBC as a TV programme, which was to be introduced by me through the BBC to be used in the Chinese TV University’s English teaching TV programme. In this course he cleverly plotted the development of the story with the learning of English, which well demonstrated Robert as a real wizard at playing with the language and full of imagination. One unique feature of Robert's English courses was that he was always able to cleverly develop storylines to create suspense, keeping learners hooked and making learning English enjoyable and entertaining. Robert was a very kind, generous man and always willing to offer help, as he did for me while I was writing my MA dissertation in Brighton. Just as I was trying to get in touch with him after more than twenty years, he has made it impossible. As a student as well as a friend, I always appreciated Robert’s kindness and I miss him greatly.

It was a privilege first to use Robert's books. These included the classic Kernel Lessons (weren't those kernels ahead of their time!); English in Situations; and the Longman Structural Readers Handbook, an essential help for writers of guided readers, including myself. His later co-authored series Success at First Certificate were standout titles of their kind, offering both students and teachers safe passage through the choppy waters of exam syllabuses. One of Robert's most interesting titles was The Fourth Dimension (1984 co-authored with Patricia Mugglestone) in which he championed expressivity (in addition to intelligibility, accuracy, and fluency) as a necessary fourth dimension to language learning and teaching.

It was an even greater privilege to hear Robert lecture, and of course to meet him. Perhaps there was something of a contrast between his books (safe, solid, secure, correct), and the man himself. He was in person a true maverick, highly individual, and sometimes unpredictable. He was never less than entertaining. His unusual Chicago background lent an air of eccentricity and glamour to his personality and presence. Put it this way: when Robert was around, you knew it.

I worked with him twice. The first time was in Milan, when I chaired a debate at which he was one of the main speakers. The motion was something along the lines of "Functions and notions have had their day". I don't remember much about what was said, but I do remember Robert having the audience of some 1,600 people in stitches.

The second time I worked with Robert was during my time as editor of the ELT Journal. His article The plausible myth of learner-centredness: or the importance of doing ordinary things well (ELTJ 1991 45:4 293-304) began with an hilarious account of a class of unresponsive Japanese businessmen, and then went on to examine closely the merits and otherwise of terms such as 'learner-centredness'. The article generated some very welcome discussion, for which, as editor, I was eternally grateful to Robert.

Given our shared interest in materials development for language learning it is amazing that I never actually met Robert O'Neill. I did, however, feel a familiarity and affinity with him as a result of using his books in my early days as a teacher. What I think I learned most from him was the importance of engaging learners through narrative. His books didn't feature extended texts from literature but they did contain ongoing stories and his language examples were often presented in narrative form. I've also been grateful to him for drawing attention to materials development as a principled pursuit which applies theory to practice for the classroom. At a time when materials development received little attention in applied linguistics he raised its profile through his course books, his journal publications and his contributions to conferences.

Robert was Series Editor for the Longman Originals Series of graded readers in the 90s. I made the mistake of writing a novel partly set in Los Angeles, and partly in Mexico, for the series. It was a detective story, and I got my local colour (or perhaps color) from guidebooks. When my manuscript bounced back, large sections had been rewritten (rather than commented on, as I had been used to) with a brusque remark to the effect that Robert had lived in Los Angeles, and my place descriptions and the distances between venues were all wrong. I learned (learnt) two things from that about Robert. Firstly, that he cared a great deal about writing and was a mightily creative and interventionist editor, and secondly that you messed with him at your peril.

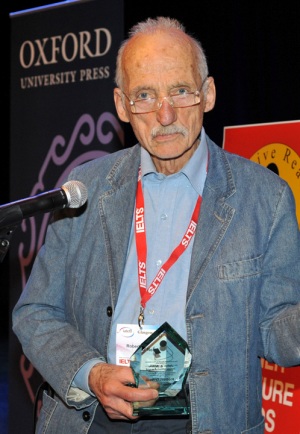

It was my great pleasure to help organize the 2012 Extensive Reading Foundation Awards at IATEFL Glasgow, and to be present when Robert received his lifetime achievement award. His remarkable acceptance speech can be found at

http://iatefl.britishcouncil.org

scroll through to 23 minutes and enjoy!

I once took part in a panel on reading at a conference in Japan (standing in, at the last moment, for Alan Maley, who was ill). Following the chairman’s instructions I spoke for my allotted 15 minutes, no more. When Robert followed he proceeded,over the next 45 minutes (!) to demonstrate that everything I had said was rubbish, and in a bravura performance of sustained wit and creativity entranced the audience he was speaking to, even if many of them, probably, wondered how I was taking it.

Of course I should have been seriously offended, but it was very difficult to feel like that. There was something (there was always something) so compelling about the passion and invention with which he spoke that even though I didn’t agree with everything he said, I couldn’t help listening with fascinated attention (mixed with a tinge of aggravation, envy and amusement).

That was the thing about Robert. He was challenging, brilliant, opinionated and hilarious. He had a creative fire that, in those days, was a major feature of the British EFL world. His coursebooks guided people of my age through our early teaching years, and entranced us with their wit and imagination. Only Robert could have written (in lesson 2, I think, of Kernel 1) ‘the man in bed with her is her husband’ and got away (at that time) with it!

I last saw Robert when I had the honour of presenting him with a lifetime achievement award from the Extensive Reading Foundation in 2013. True to form he was combatative, impassioned, and extremely moving – and he only swore three times. But hell, he was Robert O’Neill and I will never forget him.

Robert O’Neill, the philosopher from the South side of Chicago, avid reader of the New York Review of Books and impassioned debater. That was one side of Robert. The other was the iconoclastic, inventive and sometimes shocking teacher who inspired and invigorated a generation of students and teachers of English over thirty years from the seventies to the noughties. Two sides of the same coin, really.

A contemporary of Louis Alexander, another contemporary guru of ELT for Longman (as it was), Robert led the world with his books ‘Kernel Lessons Intermediate’ and his seminal ‘English in Situations’ for OUP. In Kernel Lessons he more or less invented the episodic story in ELT with ‘The Man Who Escaped’ (who can forget Coke?) and brought the teaching through drama concept to the small screen with the BBC English by Television series, ‘The Lost Secret’, which featured two international stars of today, Miranda Richardson and Tom Wilkinson. That he turned into an ‘anime’ textbook with cartoons and speech bubbles to bring the language to life.

How will I remember him? One of the most consistently original teachers and writers, the man who turned me on to Apple Macintosh (I bought two off him second hand), a great friend, a mentor and very good company. I’ll miss him.

Robert was an exceptionally bright man: a great speaker at conferences, entertaining, funny. He was often outrageous.

We were at a conference in Zaragoza once and he was in one of this difficult moods. In the evening, at a publisher's dinner he got utterly fed up with a fellow author and set out to make him leave. He started telling brothel stories, soon aided by Alan Maley. The stories, I'm sure a product of his imagination, got worse and worse. Suddenly, the person he was trying to get rid of left after complaining that 'this is disgusting'. A minute later, mission achieved, the stories stopped and we had a lovely evening.

But trouble went on and I was summoned by the organizing committee who wanted Robert out of Spain. I managed to persuade them Robert was doing a plenary, possibly the best at the conference. He was allowed to stay.

I then told Robert and he roared with laughter. As expected, his plenary was one of the best, possibly the only thing worth listening to at the conference.

I will miss him.

Robert,

My first encounter with you was when I taught in Germany, using Kernel. Little did I think I would meet you in person one day. I worked with you as an author on English Works and was inspired by you, your angle on things and your utterly unforgettable personality.

You always provoked thoughts and made me think differently about things. You will be much missed by many.

Love,

Judith Cunningham

I owe so much to Robert. After returning from Iran and a spell in a language school in Eastbourne, I went to ELC as a tutor on the RSA Dip TEFLA as it was then.

On the first day at ELC this guy showed me some work on a textbook he was working on and asked my advice on whether is was suitable for the overseas classroom.

I gave a fairly critical reply, made a suggestion for change, and this guy got up and walked out. I looked around at a silent hostile staffroom. "Who the hell do you think you are?" was the edited version of what was said.

Ye gods, I had no idea this was the famous Robert. I was mortified! But the next day Robert came and asked if I would work on the new Kernel series with him. Two lovely years, great fun, some exasperation but the greatest grounding in textbook writing ever!

I went on, doing a MA and setting up a centre for international education and management at what is now University of Chichester, and there was approached to write for OUP. We have done series that now reach at least 6 countries. I have done textbook work for the British council in Peru, Uzbekistan and Peru and ALL the time, I feel Robert looking over my shoulder giving me friendly advice to help struggling teachers yet reaching for the highest standards.

From attending a few Irish wakes in my time, this folk song is a great favourite (the tune is lovely) and I thought fitted Robert's view of life so well.

"The Parting Glass"

Of all the money that e'er I had

I've spent it in good company

And all the harm that e'er I've done

Alas it was to none but me

And all I've done for want of wit

To memory now I can't recall

So fill to me the parting glass

Good night and joy be with you all

Of all the comrades that e'er I had

They are sorry for my going away

And all the sweethearts that e'er I had

They would wish me one more day to stay

But since it falls unto my lot

That I should rise and you should not

I'll gently rise and I'll softly call

Good night and joy be with you all

A man may drink and not be drunk

A man may fight and not be slain

A man may court a pretty girl

And perhaps be welcomed back again

But since it has so ought to be

By a time to rise and a time to fall

Come fill to me the parting glass

Good night and joy be with you all

Good night and joy be with you all

Robert O’Neill stands with Louis Alexander as one of the major innovators in our profession. Both were also story-weavers. Robert introduced extensive reading into the Kernel Lessons series, with The Man Who Escaped. He was later the Series Editor of Longman Structural Readers, as well as an author, before they were subsumed into Penguin Readers.

Where do I start? I’m looking at the bookshelves in my office, where I think and hope I have a complete set of Robert’s work. Periodically the shelves fill, and some ELT books get shifted to the book storeroom upstairs, but none of Robert’s work ever makes that journey.

When I began teaching in Bournemouth, Robert O’Neill was already a local legend at Eurocentre, just around the corner from Anglo-Continental where I worked. He was known as the author of English in Situations (OUP 1970) which I consider an essential tool to this day. Robert perfected the art of finding a brief, interesting situation which crystallized a structural point. For years I kept a copy with me because if a student came up with a problem you could use a situation with leading questions which made it clear. Then you had an invention exercise where students created their own explanatory situations.

Kernel Lessons Intermediate (with Roy Kingsbury & Tony Yeadon) was the textbook I considered the benchmark of excellence when I started writing. I didn’t know Robert then, but Bernie Hartley arrived at Anglo-Continental and he had worked with Robert closely on teacher-training at Eurocentre, and on the analysis of the micro-skills of the classroom teacher. Both Robert and Bernie could spend 90 minutes on something like eye contact, and be funny and riveting at the same time. Robert taught the early RSA Cert. TEFL courses in Bournemouth.

Robert was also a collaborator on English Grammatical Structure with Louis Alexander, R.A. Close, and W. Stannard-Allen (Longman 1975) which was the clearest analysis of a progression through English grammar from simple to complex, with each stage adding just one new element. Bernie Hartley called it “the textbook author’s bible.” Robert’s wonderful essay in the ELTJ on structural and functional approaches was “My Guinea Pig Died With Its Legs Crossed” pointing out that knowledge of structural elements enable us to understand unpredictable and probably unique sentences, and I quoted him for years.

When we were deciding on publishers, Bernie went to see Robert to ask for advice, and he told us in no uncertain terms to go with OUP. Robert moved from Bournemouth to Brighton, and he came along to our very first Streamline English talk in Brighton. The talk before us was on a new Oxford dictionary, and Robert gleefully pointed out a long list of “circular definitions”, the sort of thing where “close” is defined as “shut” and “shut” is defined as “close.” He ripped it apart, something he was inclined to do from the audience when he disapproved. Just ask Stephen Krashen. We had to go on next and I was terrified, but he smiled and nodded enthusiastically throughout our talk, then made a little speech to the audience at the end saying he thought the book excellent. As his own Kernel One was in direct competition, this was extremely generous.

viney-athens-palso-2

Athens, 1979, Robert and me listening very seriously

I got to know Robert as a friend on our various travels. I still recall a 1979 conference in Athens, where Robert, Brian Abbs and I spent happy hours arguing the ins and outs of textbook writing. Then in Japan around 1980, Robert was touring with Longman, and I was with OUP. We both got dropped off by the Japanese local staff at about 7 pm every night, and spent the evenings putting the world to rights. In Osaka, a hurricane meant the cancellation of both of our talks. We spent the afternoon in the hotel coffee shop, which in 1980 only had sweet Japanese rosé wine. Robert insisted on buying both the straw-covered display litres of Chianti … they were most reluctant to sell them … and we polished them off. I’ve rarely enjoyed wine more.

Later, when Robert wrote Success At First Certificate and he moved from Longman back to OUP, we found ourselves travelling together. There was an OUP Sunday conference in Thessaloniki I remember fondly. I was already in Greece, but Robert was flying into Athens from London, changing planes and joining me. His flight from London was massively delayed, and the connection missed. OUP put him in a taxi at 2 a.m. to get to Thessaloniki, roughly a six hour drive. He arrived for breakfast, and I asked him if he’d had any sleep. No, of course not. He’d spent the journey improving the driver’s English and learning Greek for himself. That was a strange day. We did a Question and Answer panel session at the end of the day, and a beautiful lady got up and started asking us how to teach her two year old child English. It was irrelevant and she went on and on and on and on. Everyone was bored. Robert and I went to the bar afterwards where he berated me for not shutting her up. I pointed out his teacher-training expertise and seniority and asked why he hadn’t shut her up. “But she was gorgeous!” he said, “Impossible for me to do. And I was exhausted after the taxi ride! And you’re a married man. No, Peter, I blame you!’

A tour with Robert was not only entertaining, but would make me feel guilty. I would do the same well-honed talk with the same carefully-placed jokes and anecdotes on teaching with video every day of a tour, but Robert would do a completely different talk on Success at First Certificate every single day, using different examples from the book. Every one of them got the audience talking.

We both got delayed at Warsaw a few years later and we spent the afternoon in the airport restaurant. Robert could switch languages at the drop of the hat. Conversation was a dizzying tour of quotes in various tongues. He could imitate any accent in English perfectly too, as well as code-switching at speed. He used to describe himself as an Irish-Jewish-American who lived in Britain. When he wasn’t in Germany, Poland, Turkey, Spain, Cuba, Uruguay or Japan. Having been with Robert with American teachers and British teachers, he could code switch at will between Chicago-accented American (his home town) and RP British. His background, like so many of our profession, was acting and drama. He may not have had early formal qualifications, but he was capable of arguing any point of linguistics or applied linguistics with anyone. I never managed to find a topic from Gregorian chant to the political philosophy of Rousseau (to name two I know we discussed at random) that Robert didn’t know about. I used to play a CD with the slow section of Ravel’s Piano Concerto in G before my talks. I never mentioned the title of the piece or the pianist. The first time Robert was there, he said “I’m glad you played the Bernstein version. Easily the best.” He was of course correct. He was in the true sense, a Renaissance man.

Robert was also a natural psychologist, and would ask soul-searching questions after around ten minutes of starting a conversation, and due to his charisma, you would find yourself compelled to answer.

In many ways, Robert felt he was treated poorly in later years by the publishers he made so much money for, and whose credibility in ELT he had helped establish. I know from our conversations that he couldn’t get a publisher for some of his later ELT work, which is astonishing and the publishers’ loss. He was difficult to work with for commercial publishers, because of his integrity. If he got 90% through a book and felt it wasn’t right, he’d simply start again.

I last saw him three years ago in Brighton, where he came to my talk on reading. He was completing his Ph.D on Holocaust Studies, and we spoke about it. He was in vibrant form, shocking the more faint-hearted in the audience (as ever) with some typically robust and piercingly accurate comments on the current state of ELT.

Last word to Robert, from a 2000 article:

What EFL needs today is writers capable of developing skills that writers in other genres regard as essential: they must be able to develop the kinds of story, plot and character that can keep groups of very different learners interested in the language. The texts and conversations they write must exemplify as naturally as possible how people speak and write outside the classroom. However, the texts and dialogues must also serve a distinct pedagogic purpose.

Amen. That was Robert. I shall miss him.

|