The Impact of Motivation to Read and Syntactic Knowledge on Reading Comprehension in an EFL Setting

Jerome C. Bush, Turkey

Jerome C. Bush is an English language instructor at University of Economics in Izmir and a PhD student at Yeditepe University in Istanbul, Turkey. E-mail: jerome.bush@izmirekonomi.edu.tr

Menu

Abstract

Background

Reading comprehension

Syntax and reading

Motivation in second language learning

Motivation for reading in a second language

The current study

Participants

Procedures

Results

Discussion and implications

Limitations

Acknowledgements

Appendix

References

Reading in a foreign language is a complex activity that makes cognitive demands on students and is affected by personal and social factors. In a context where English is not present to any large degree, reading in a foreign language generally becomes confined to a school activity. For students to be successful at reading they must have knowledge of the target language and a desire to spend the time and energy on reading. This study looks at syntactic knowledge and motivation as factors in reading comprehension. A syntactic knowledge score was derived by averaging z-scores from three grammar test scores. Motivation levels were determined by using the Motivation for Reading Questionnaire (Wigfeild & Guthrie, 1997). The Motivation for Reading Questionnaire (MRQ) has been translated into a number of languages and widely used in research around the world. However, this is the first time it has been translated into Turkish and used in Turkey. Results suggest that syntactic knowledge is a stronger predictor of reading comprehension scores than motivation, and that Turkish students are motivated by the extrinsic utility value of reading in English. The implication for teaching is that although getting students to love reading in English is laudable, effective grammar instruction better facilitates reading comprehension.

English as a foreign language (EFL) is generally differentiated from the teaching of English as a second language (ESL) based on context. English is considered a foreign language when it is taught in countries where English is not spoken by the general populace. These distinctions can become blurry in certain countries (e.g. India, Nigeria, and Singapore) where English is an official language and a required subject in schools, but may not be the primary language spoken at home (Kachru, 1992). However, the country of Turkey, where this study was conducted, can definitely be said to be an EFL setting because Turkish is the primary language and English has no recognized official status (Selvi, 2011).

Turkey has been struggling to improve its education system (Alonso, McLaughlin, & Oral, 2011). According to the World Bank report produced by Alonso, et al, Turkey enjoys a 98.4% enrollment in primary schools. Although this almost universal school enrollment is laudable, the quality of education lags behind many OECD countries. The literacy rate as of 2010 was an impressive 97.8% (United Nations Statistics Division, 2012). However, this represents a basic form of literacy, such as ability to fill out a form and read a simple paragraph. An OECD report indicates that less than half of the adults in Turkey (42%) have completed high school as of 2009 (OECD, 2011). The OECD average for secondary education attainment in 2009 was 82%. To sum up, Turkey has been making gains in education, particularly in primary education, but is still behind other countries in many aspects of education.

In the Turkish context, it is not easy to get children to read. Among the problems are lack of parental support, economic problems, the test-based educational system, lack of comprehension, lack of time, and the lack of a reading habit (Arici, 2009). However, other research has found that Turkish children are moderately motivated to read (Şahbaz, 2012; Baş, 2012). These studies found that gender, socio-economic status, and parents’ education, school type, and computer usage could be mitigating factors. A large scale study (N=443) of Turkish university students revealed that those students engaged in a foreign language major were more motivated to read than those who were enrolled in other programs (Erten, Topkaya, & Karakas, 2010). While this may not seem so surprising, it indicates that the “extrinsic utility value of reading” is a significant motivational factor for Turkish students.

On the whole, the research regarding Turkish students’ reading habits and abilities paints a bleak picture. However, the statement that “Turks don’t like to read” is a broad overgeneralization that implies a negative judgment. It is very important that research be conducted to determine if Turkish people actually have a tendency to read less than other cultures, and if so, what factors contribute to that situation. Once such determinations are made, changes to curriculums, institutions, and policies can be considered and implemented if desired.

This study seeks to add to the body of knowledge that can be used to inform curricular and policy decisions. An examination of reading in the Turkish context may also provide insight into reading in other context. This study examines an EFL secondary school to see to what extent Syntactic knowledge gained from grammar instruction can predict reading comprehension scores. It also looks at which aspects of reading motivation have the greatest impact on reading comprehension scores. Furthermore, it compares L1 (Turkish) reading motivation with L2 (English) motivation. Conclusions, discussions, and implications will follow.

Before embarking on an examination of factors that impact reading comprehension it is important to consider a working definition of the concept. Reading comprehension is widely seen as being composed of two main factors, text processing and recognition of the ideas embedded within the text (Grabe, 2009). Although a variety of reading comprehension models exist, they all include these two aspects to a greater or lesser degree. The perspectives on reading that emphasize content comprehension are often referred to as top-down, where the models that emphasize decoding are often designated as bottom-up.

Each of these major components includes many sub skills (Gough & Tunmer, 1986). For example decoding includes word recognition, phonetics, orthography, semantics, and syntax. The extraction of ideas from text requires both long-term and short-term memory as well as the ability to infer and visualize. Therefore, we can say that reading comprehension is a complex skill involving many sub skills.

Additionally, there are many social factors which impact reading and reading comprehension. These factors include parents’ level of education, school facilities, importance of reading to the local society, socio-economic status (Damber, Samuelsson, & Taube, 2012). Another important factor in reading is motivation (Wang & Guthrie, 2004). Although these factors do not define reading comprehension, they are important factors and cannot be ignored. For the purposes of this paper then, we will define reading comprehension as a combination of top-down and bottom-up processes which are affected by social factors. The measurement of reading comprehension will be discussed in the procedures section.

A large body of research exists on the interaction of vocabulary knowledge and reading comprehension in a first language (e.g. Anderson & Freebody, 1979; Nagy, 1988). In a second language, Nation (2001) examined this relationship in depth. This extensive body of research indicates that there is a reciprocal relationship between vocabulary knowledge and reading comprehension. Vocabulary knowledge is a crucial component of reading comprehension and exposure to print is a valuable component of vocabulary acquisition.

The role of syntax on the other hand, has not been as extensively explored. Syntax can be considered one of the aspects of vocabulary knowledge (Nation 2001; Zimmerman, 2008). However, in the EFL context and many ESL contexts, grammar is so much a part of English instruction that it is often seen as synonymous with the language itself. In these contexts, vocabulary acquisition and the development of practical language skills is secondary to the knowledge of grammatical rules. This is often due to a focus on grammar tests as a means for course evaluation, but may also be due to teachers’ conception of English and English teaching. Syntax is a subcomponent of grammar, which can also include phonetics, morphology, semantics, and pragmatics.

The role of syntax in reading comprehension has been explored in regards to L1 children who have reading impairments (Stein, Cairns, & Zurif, 1984). The Structural Deficit Hypothesis or SDH is the common viewpoint that poor reading stems from inadequate syntactic knowledge (Shankweiler & Crain, 1986). The opposing viewpoint is that reading deficiencies are caused by inability of phonetic processing. This is known as the Processing deficit Hypothesis or PDH. These hypotheses pertain to L1 reading impaired children. Although this body of research does not directly apply to EFL reading, it does highlight the point that syntactic knowledge is an important component of reading comprehension.

The importance of syntax for reading impaired learners in a L1 environment has been established. However, Grabe (2009) makes it clear that an L2 reader is very different from a poor L1 reader. In an L2 environment, some researchers have postulated that reading ability in the first language can transfer to a second language (Cummins, 1979). The contention is that basic decoding ability is only learned once and applied to languages that are learned later. From this perspective, it is important that the L1 be sufficiently developed for transfer to take place. This is known as the Threshold Hypothesis and it has been supported through other independent research (Martohardjono, et al., 2005). Martohardjono, et al. found that certain syntactic structures are better predictors of comprehension success than others. Coordination and subordination were found to be particularly good predictors of comprehension. They found that this syntactic knowledge was a better predictor of comprehension success than phonological or lexical knowledge. This study was conducted in an ESL environment among Spanish-English bilingual children. In a different setting, with a different language combination, the results would surely vary. It is unlikely though, that syntactic knowledge would ever be completely removed as a predictor of reading comprehension.

In Canada it was found that syntactic knowledge was a significantly contributing component of reading comprehension, although not the dominant predictor (Nassaji, 2003). A study in Puerto Rico found syntactic knowledge to be a factor in reading comprehension (Blau, 1982). Although the study purported to be examining groups of ESL learners, Puerto Rico is a Spanish speaking American territory and the situation may be closer to an EFL setting. A study conducted in a clearly EFL setting in Japan and found syntactic knowledge more predictive of reading comprehension scores than vocabulary knowledge (Yano, Long, & Ross, 1994). Knowledge of syntax has firmly been established as an important factor contributing to reading comprehension. However, the studies show those proficient at reading have a set of skills which includes knowledge of syntax. The studies do not show that acquiring syntactical knowledge necessarily leads to reading proficiency. It is possible that a student may gain knowledge of syntax through grammar lessons and still not be a strong reader.

Motivation is an important psychological construct that can be considered in various ways. Variance occurs in both the level and type of motivation. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations, which are part of Self-Determination Theory, are two of the most widely discussed orientations of motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2000). The distinction is simple, intrinsic motivation is a force to do something because of the pleasure derived from the activity while extrinsic motivation is focused on the result or outcome. In education, intrinsic motivation is considered the stronger of the two and results in higher levels of creativity and learning. However, extrinsic motivation does not necessarily mean reluctance or resistance to doing a task. Extrinsically motivated students can willingly accept tasks as being useful and put forth great deals of effort to reach a certain goal without any remorse. Although extrinsic motivation has been described as weak in much of the literature, much of what motivates people is related to social demands and a desire for advancement.

It should be noted that Self-Determination Theory is just one of a host of general motivational theories. Additionally, over the past forty years, a number of theories have been promulgated relating specifically to motivation for learning a second language (for an excellent review of these theories see Dörnyei, 2003).

Specific to Language learning, and related to intrinsic-extrinsic motivation, are the ideas of instrumental and integrative motivation (Gardner & Lambert, 1959). These constructs vary from intrinsic-extrinsic motivation in some very important ways. Instrumental motivation is the desire to learn a language to obtain a specific goal related to that language, for example getting a job. Integrative motivation has to do with the ability to join a group or interact with a community by using a specific language. Although many people relate instrumental motivation to extrinsic motivation and integrative with intrinsic, this is not always the case. For example, if one moves to a foreign country, the need to integrate may be strong and a person may be extrinsically motivated by that goal. That person will learn the language because it is useful, not because he or she has an innate desire to learn the language. Although Gardner’s theories have been strongly criticized, they continue to exert influence and are widely discussed (Mori, 2002).

Whether the motivation comes from within, or a desired outcome, no learning will occur unless some motivation is present (Guilloteaux & Dörnyei, 2008). Good textbooks and well-designed curricula are insufficient for language acquisition. Fortunately, motivational theory has progressed to the point where it informs teaching practice. Currently, all good teacher education programs include a motivational component in the curriculum.

Motivation for reading is based on the general theories of motivation. Reading is a complex activity, involving many sub skills as well as personal, institutional, and social factors. As a result, motivation for reading has been found to be multifaceted (Wigfeild & Guthrie, 1997). Wigfield and Guthrie’s (1997) study was done in an L1 context, and the constructs subsequently reflect motivational factors for L1 reading. Mori (2002) applied these constructs, modified for an EFL setting, to university students in Japan. Mori found that the components of motivation for reading in an EFL setting closely resembled the components of motivation identified by Wigfield and Guthrie in an L1 setting and by Gardner in an ESL setting. Mori found that EFL motivation for reading follows the general form of motivation described in expectancy-value theory (Wigfield & Eccles, 2000). Expectancy-value theory was one of the four motivational theories which contributed to the Wigfield/Guthrie model of motivation.

An interesting and relevant study was done recently in a Turkish context, at Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University (Erten, Topkaya, & Karakas, 2010). These researchers asked open-ended questions about reading to 123 students and analyzed the results. The final version of the scale included 51 statements for Likert-type responses. Four factors were determined as accounting for most of the variance (58.7%) in student response regarding attitudes towards reading in a foreign language. The factors were named, “intrinsic value of reading”, “extrinsic utility value of reading”, “reading efficacy”, and “foreign language linguistic utility”. Wigfield and Guthrie, in their Motivation for Reading Questionnaire (MRQ) developed 53 statements pertaining to 11 constructs grouped into four factors. These factors are “intrinsic motivation”, “extrinsic motivation”, “reading efficacy”, and “social reasons for reading”. Although some overlap is obvious, the final factor in the Erten, et al. study “foreign language linguistic utility” is unique. This supports Mori’s contention that reading in an EFL environment must be examined differently than an L1 or ESL context. Indeed, Wigfield and Guthrie (1997) stressed the multifaceted nature of reading motivation and called for additional research in a variety of contexts.

The body of research on motivation for second or foreign language reading cannot be said to be extensive. However, the concepts of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation are pervasive as well as the idea that readers are motivated by many factors (Dhanapala, 2008). Additionally, the motivational factors identified in the L1 research seem to remain consistent for L2 contexts. In other words, the concepts of intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, utility, and integration, are valid concepts for measuring reading motivation in an EFL setting.

Given the importance of reading to education, where it is both a subject of study and a tool used for other areas of study, it was felt that a better understanding of the motivation for reading was required. Additionally, the EFL context presents a challenge to learners in that there is generally only limited contact to native speakers of the target language. Also, in Turkey, as in many countries, much of the curriculum is centrally planned and testing is the sole means of evaluation. Therefore, reading is not considered as important as grammar and there is a perception of a reluctance to read. With this in mind, and considering the above literature review, the following research questions were developed:

- Does the level of syntactic knowledge acquired during grammar lessons predict reading comprehension scores?

- What factors, if any, motivate Turkish students to read both in L1 and L2?

- Do any of the motivational factors predict reading comprehension success?

Hypotheses:

- Syntactic knowledge is a necessary, but insufficient, factor in reading comprehension success.

- Turkish students are motivated to read by both intrinsic and extrinsic factors.

- Intrinsic motivation will be the best predictor of reading comprehensive scores.

The school where the study took place is a high school near the outskirts of Istanbul. The participants (N=229) were all Turkish ninth grade students. The gender distribution was fairly equal, 52% female and 48% male. The student ages range from 14 to 16 with the majority (87%) being 15 years old. The school specializes in foreign language instruction and 9th grade students have ten hours of English and two hours of German every week. Students come from a variety of backgrounds and have very different levels of English language ability. All students attend six hours of “main course” English lessons, where the focus is grammar, and four hours of “skills” where the focus is on reading, writing, listening and speaking. Students are not grouped according to linguistic ability and each class is a mixed-ability class.

Motivation data were collected by administering the Wigfield and Guthrie MRQ twice. The first time the survey was given students were asked to respond according to their reading habits in Turkish. The second time the survey was administered was one week later, and the students were asked to respond according to their reading habits in English. One week was given between the surveys so that students would have a more or less fresh view of the survey. Responses were tabulated in Excel and transferred to SPSS (version 20) for statistical analysis.

The full MRQ was used as revised by Wigfield and Guthrie in 1997. It was decided not to alter any of the items because the instrument has been validated. This also makes the results comparable to other studies which have used the MRQ. The survey was translated into Turkish by the school’s English department head teacher. A Turkish version was used to ensure that even the students who are not proficient in English could participate. The two surveys were given during the same period one week apart. The surveys were given by Turkish teachers of English, not native speakers. The teachers could give the instructions in Turkish and were able to answer questions in Turkish. The teachers were coached in how to administer the survey and knew the reason the survey was being done.

The syntactic knowledge score was extrapolated from the grammar test scores that the students had taken during the semester. All of the ninth grade students take the same English tests. The test is designed by the class level coordinator, who is also a classroom teacher, and checked by the department head. Because validity and reliability had not been established for these teacher generated tests, raw scores were not used. Instead the scores were converted into z-scores to reduce the effects of test variability. The three z-scores were then averaged and multiplied by 100 to create a composite “syntactic knowledge score”. The scores are only comparable within the sample population. However, the scores will indicate which students in the sample have been most successful on the English exams, which require an understanding of syntax to pass.

The reading comprehension scores was likewise extrapolated from teacher generated exams using z-scores. The exams were generated for the reading of a class book, “Zorro”. It was decided to use this instead of a standardized test, such as the Nelson-Denny reading comprehension test. Standardized tests of this nature, which include only short readings, require more of a problem-solving ability than real reading comprehension ability. A standardized comprehension test for an extensive text (book length) was both not known about and not feasible for the author, the composite reading comprehension score was created. The reading comprehension score, similar to the syntactic knowledge score, are for comparison purposes only and cannot be compared to outside populations. In other words, a student who has a high score on this syntactic knowledge score may not have a better understanding of syntax than a student from another school. However, we can see how a high syntactic knowledge score corresponds to the reading comprehension score and the motivation scores. Therefore, the results will have some generalizability to the larger population based on the comparison.

To answer research question one, a simple linear regression was performed to determine the predictive quality of syntactic knowledge on reading comprehension scores. The assumptions of linearity, independence of errors, homoscedasticity, unusual points and normality of residuals were met. The linear regression established that syntactic knowledge significantly predicted reading comprehension F (1, 226) = 154.99, p <.0005, R2 =.407. Therefore, knowledge of syntax explains approximately 40% of the variance in reading comprehension scores. Adjusted R2 = .404, which indicates a medium to strong effect size. Hypothesis one is not supported by this finding.

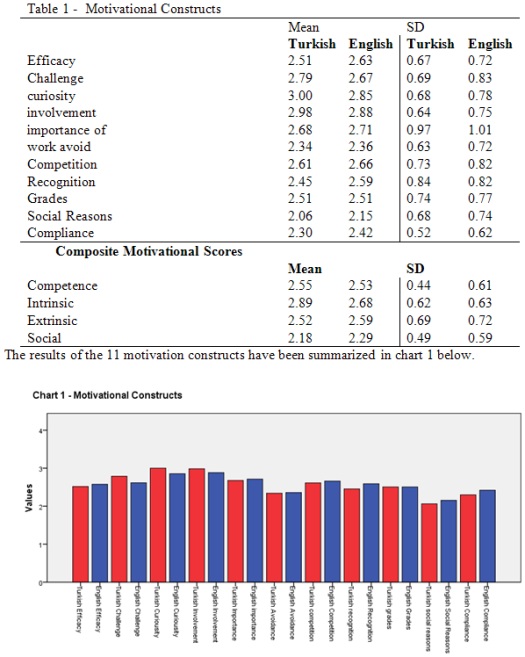

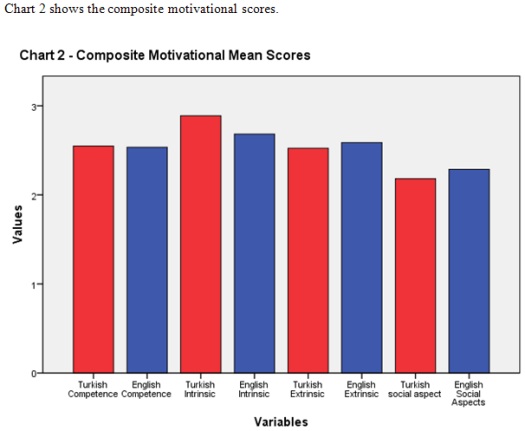

Question two requires only descriptive statistics, which can be found listed in table one below. A total of 204 students filled out the MRQ regarding reading in Turkish, but only 155 students responded to the MRQ regarding reading in English. The sample size is different because two classes did not complete the MRQ surveys for reading in English. Although this data is missing, the sample is still large enough to provide for useful comparisons. The descriptive statistics are provided in table 1 below. The composite scores are made up of combinations of the constructs. Competence includes Efficacy, Challenge, and work Avoidance. Intrinsic motivation includes curiosity, reading involvement, and the importance of reading. Extrinsic motivation includes competition, recognition, and grades. Social aspects are social reasons for reading and compliance.

Based on these results, hypothesis two is supported. Students are both intrinsically and extrinsically motivated to read in both languages.

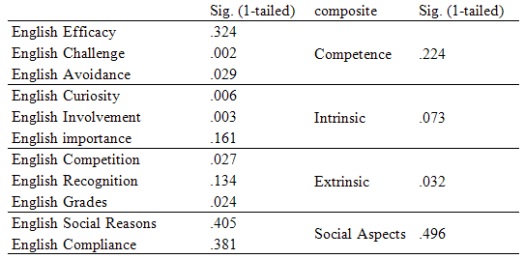

Multiple regression analysis was performed to answer the third research question and determine the predictive value of the eleven motivational constructs on reading comprehension. The assumptions of linearity, independence of errors, homoscedasticity, unusual points and normality of residuals were met. The English construct variables were used because the reading was in English. These variables significantly predicted reading comprehension scores F (11,143) = 2.52, p = .006, adj. R2 = .098. Not all of the constructs contributed significantly to the overall predictive value of motivation as can be seen in table 2 below. Additionally, the adjusted R2 of .098 indicates a small effect size.

To further examine the predictive value of motivation, multiple regression was conducted on the four composite English reading motivational scores. Again, all the assumptions were met. These variables also significantly predicted reading comprehension, F (4,150) = 2.54, p = .042, adj.R2 = .039. In this case, only Extrinsic motivation was found to be a significantly contributing factor (p =.032). Intrinsic motivation was nearly significant (p = .073), with competence contributing only slightly (p = .224) and social reasons hardly at all (p = .496). These results can be seen in table 2 above. Hypothesis three is not supported by these results.

The purpose of this study was to examine how motivation and syntactic knowledge impact the reading program for EFL students. It was found that knowledge of syntax as inferred from converted grammar test scores was an important determinant in the reading comprehension scores. The implication for teaching is that grammar lessons can’t be ignored or minimized in the curriculum. Grammar and syntax can be taught and learned in many ways. There are those who support the implicit acquisition of language through exposure. However, in the EFL context, such exposure may not be either available or desirable. It may not be appropriate to speak English or listen to English television when grandmother is in the house.

In every model of reading comprehension, vocabulary and syntax have a place. Vocabulary has been firmly established as a predictor of reading comprehension. The results of this study now show that syntax is also important. It was found to be a much stronger predictor of reading comprehension success than motivation. Therefore the literature lovers who want to foster a love of the classics in their students have cause for alarm. While fostering the desire to read is laudable, and should continue, students need to basic vocabulary and grammar in order to be successful. Give the students love, but do not skimp on the vocabulary, grammar, and syntax.

As for the motivation, the idea that Turks don’t like to read was clearly not supported. When one looks at the chart, it is apparent that these students are motivated to read. All the scores are above 2 for both English and Turkish reading in every category of the constructs and the composite scores. Curiosity and involvement are high in both English and Turkish. These students feel they can read, they like to read, and they get a benefit from reading. However, reading doesn’t seem to be such an important part of their social life.

Additionally, the results for reading in Turkish and in English are surprisingly similar. Looking at the individual answers the largest variance is less than half a point (.42) on the statement “I read to learn new information about topics that interest me.” The students do this more in Turkish than in English. The biggest difference in favor of English was the statement “I always do my reading work exactly as the teacher wants it.” This makes some sense because students are more extrinsically motivated in English and therefore more prone to following the instructions of the teacher. Another interesting difference was “I enjoy reading books about people in different countries”, which the students enjoy doing in English more than Turkish (2.70 and 2.95 respectively). In spite of these interesting differences, none of the scores were even half a point different for reading in English or in Turkish.

It should be noted that some students (at least seven) either only partially filled out the form or simply circled “1” for every statement. These surveys were not included in the study. The circling of “1” for every question, however, seems to be an attempt to send a message. The message seems to be quite negative and it is unlikely that these students have any motivation to read at all. The pedagogical implication is that when students say they don’t like to read, they may not be speaking for the whole class. However, if a class thinks they can get out of a difficult assignment, they may back up the complainer. In other words, if a teacher refuses to back don’t on a reading assignment, many students may secretly thank that teacher. Of course teachers must make their own decisions in their classrooms. I would just hate to see good students suffer because of a vocal few.

Where Turkish students are clearly motivated to read, this motivation does not ensure success. This study could not support motivation as a strong predictor of reading comprehension scores. However, it seems perilous to ignore motivation and not attempt to motivate students. EFL students are often motivated by the utility of knowing English, which has become a lingua franca. This extrinsic, instrumental motivation can be quite powerful and teachers may do well to remind student of the jobs and success they can get from learning English. The final message is that teachers should remain focused on developing linguistic competency and add in motivating components whenever possible.

This study was limited to only one school in an EFL environment. Additionally, the surveys were given at the end of the first semester, when students were potentially feeling test fatigue and looking forward to the long semester break. They may not have focused on the survey and results given at another time may yield very different results. This study also focused on only one age group in a school that is known for teaching English. Other age groups from other schools may respond very differently. The lack of research in this area was also a problem. It was difficult to generate hypotheses and develop a strong theoretical framework. It is the strong desire of the author of this paper that more research in this important area be done and published for all to share.

The author would like to thank Professor Dr. Akyel for inspiration. The idea to conduct this research project was hers. Professor Dr. Farhady is very much appreciated for advice on statistical matters. Thanks also go to the students who participated in this study. A very special debt of gratitude is owed to the wonderful teachers who helped in this study. The world is a better place because of their selfless devotion. It is hoped they can keep their own spirits up as they try to motivate students who would rather not be motivated.

Note: the English version of the questionnaire is accessible at

www.cori.umd.edu/measures/MRQ.pdf

and his article is the first time this ınstrument has been translated into Turkish.

OKUMA ANKET FORMU İÇİN MOTİVASYONLAR (MRQ)

Wigfield & Guthrie, 1997

1= Benden çok farklı

2= Benden biraz farklı

3= Benim gibi biraz

4= Benim gibi çok

| 1 | Okumada en iyi olmayı seviyorum. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 2 | Kitaplardaki sorular beni düşündürdüğü zaman daha çok seviyorum. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 3 | Ben derecemi yükseltmek için okurum. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 4 | Eğer öğretmen ilginç şeyler üzerine tartışırsa, ben o konuyla ilgili daha fazla şey okuyabilirim. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 5 | Zor ve sorgulayıcı kitapları severim. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 6 | Uzun, karmaşık hikayeler ya da hayal ürünü hikayeler okumayı severim. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 7 | Gelecek yıl okumada daha iyi olur muyum bilmiyorum. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 8 | Eğer kitap ilginçse, okumasının zorluğunu umursamıyorum. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 9 | Arkadaşlarımdan daha fazla doğru cevap vermeye çalışıyorum. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 10 | Benim favori konularımla ilgili şeyleri okuyorum. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 11 | Sık sık ailemle beraber kütüphaneleri ziyaret ederim. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 12 | Okuduğum zaman kafamda resimler oluşuyor. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 13 | Kelimeleri çok zor olan şeyleri okumayı sevmiyorum. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 14 | Canlı olan şeylerle ilgili okumak hoşuma gidiyor. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 15 | Ben iyi bir okuyucuyum. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 16 | Okuyarak genellikle zor şeyler öğreniyorum. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 17 | İyi bir okuyucu olmak benim için çok önemli. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 18 | Ailem sık sık benim okumada harika işler yaptığımı söylerler. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 19 | Benim ilgimi çeken konular hakkında yeni bilgiler öğrenmek için okuyorum. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 20 | Eğer proje ilginçse, daha zor materyaller okuyabilirim. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 21 | Ben okuyarak sınıftaki birçok arkadaşımdan daha fazla öğreniyorum. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 22 | Hayali şeylerle ilgili hikayeleri okurum ve inanırım. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 23 | Zorunlu olduğu için okuyorum. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 24 | Kelime sorularını sevmiyorum. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 25 | Yeni şeylerle ilgili konuları okumayı seviyorum. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 26 | Erkek kardeşime ya da kız kardeşime sık sık okurum. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 27 | Diğer yaptığım aktivitelerle kıyasladığımda, iyi bir okuyucu olmak benim için çok önemli. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 28 | Öğretmenimin iyi okuduğumu söylemesi hoşuma gidiyor. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 29 | Benim hobilerimle ilgili daha çok şey öğrenmek için okuyorum | 1 2 3 4 |

| 30 | Gizemli şeyler hoşuma gider. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 31 | Ben ve arkadaşlarım mesleklerle ilgili şeyleri okumayı seviyoruz. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 32 | Karışık hikayeleri okumak hiç eğlenceli değil. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 33 | Daha fazla macera kitapları okurum. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 34 | Okumayla ilgili okul çalışmalarını mümkün olduğu kadar az yapıyorum. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 35 | İyi kitaplarda sanki karakterlerle arkadaş olmuş gibi hissediyorum. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 36 | Okuma parçalarını bitirmek benim için çok önemli. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 37 | Arkadaşlarım bazen benim iyi bir okuyucu olduğumu söylerler. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 38 | Seviyeler okumada ne kadar iyi olduğunu görmek için iyi bir yoldur. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 39 | Arkadaşlarıma okumayla ilgili okul çalışmalarında yardımcı olmayı seviyorum. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 40 | Çok fazla karakter olan hikayeleri sevmiyorum. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 41 | Arkadaşlarımdan daha iyi okumak için daha çok çalışmaya gönüllüyüm. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 42 | Bazen aileme okurum. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 43 | Okumam için övgüler almam hoşuma gidiyor. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 44 | Kendi ismimi iyi okuyucular listesinde görmek benim için önemli. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 45 | Arkadaşlarımla okuduğum şeyler üzerine konuşuruz. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 46 | Okumamı her zaman zamanında bitirmeyi deniyorum. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 47 | Birileri benim okumamı fark ettiğinde mutlu oluyorum. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 48 | Ailemle okuduğum şeyler hakkında konuşmayı seviyorum. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 49 | Okuduğumuz şeyle ilgili tek cevap veren kişi olmak hoşuma gidiyor. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 50 | Ben dört gözle okuma derecemi araştırırım. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 51 | Okuma çalışmalarını kesinlikle öğretmenim istediği için yapıyorum. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 52 | Okumamı arkadaşlarımdan önce bitirmeyi seviyorum. | 1 2 3 4 |

| 53 | Ailem bana okuma derecemle ilgili soru sorar. | 1 2 3 4 |

Alonso, J. D., McLaughlin, M., & Oral, I. (2011). Improving The Quality And Equity Of Basic Education In Turkey Challenges And Options. Washington, DC 20433, USA: Wolrd Bank.

Anderson, R. C., & Freebody, P. (1979). Vocabulary Knowledge. Technical Report No. 136. Urbana, Il., USA: Center for the Study of Reading.

Arici, A. F. (2009). Problems in Turkish Reading Education: Interviews with Teachers. Reading Improvement 46:3, 123-129.

Bas, G. (2012). Reading Attitudes of High School Students: An Analysis from Different Variables. International Journal on New Trends in Education and Their Implications, 47-58.

Blau, E. K. (1982). The Effect of Syntax on Readability for ESL Students in Puerto Rico. TESOL Quarterly, 517-528.

Cummins, J. (1979). Linguistic interdependence and the educational development of bilingual children. Review of Educational Research, 40, 222-251.

Damber, U., Samuelsson, S., & Taube, K. (2012). Differences between overachieving and underachieving classes in reading: Teacher, classroom and student characteristics. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 339-366.

Dhanapala, K. V. (2008). Motivation and L2 reading behaviorsof university students in Japan and Sri Lanka. Journal of International development and cooperation, 1-11.

Dörnyei, Z. (2003). Attitudes, orientation, and motivations in language learning: Advances in theory, research, and applications. Language Learning 53, 3-32.

Erten, I. H., Topkaya, E. Z., & Karakas, M. (2010). Exploring Motivational Constructs in Foreign Language Reading. Hacettepe Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi (H. U. Journal of Education), 185-196.

Gardner , R., & Lambert, W. (1959). Motivational variables in second language acquisition. Canadian Journal of Psychology, 266-272.

Gough, P., & Tunmer, W. (1986). Decoding, Reading, and Reading Disability. Remedial and Special Education 7: 6, 6-10.

Grabe, W. (2009). Reading in a Second Language: Moving from theory to practice. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Guilloteaux, M., & Dörnyei, Z. (2008). Motivating language Learners: A Classromm-Oriented Investigation of the Effects of Motivational Strategies on Student Motivation. TESOL Quarterly, 55-77.

Harris, D. (2009). Establishing an L2 Reading Motivation Framework for Tertiary Education. In D. Anderson, M. McGuire, & (Eds.), Cultivating Real Readers (pp. 111-120). Dubai: HCT Press.

Kachru, B. B. (1992). World Englishes: approaches, issues and resources. Language Teaching, 1-14.

Martohardjono, G., Otheguy, R., Gabriele, A., de Goeas-Malone, M., Szupica-Pyrzanowski,

M., Troseth, E., . . . Schutzman, Z. (2005). The Role of Syntax in Reading Comprehension: A Study of Bilingual Readers. International Symposium on Bilingualism (pp. 1522-1544). Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press.

Mori, S. (2002). Redefining Motivation to Read in a Foreign Language. Reading in a Foreign Language, 91-110.

Nagy, W. (1988). Teaching vocabulary to improve reading comprehension. Urbana, Il.: National Council of Teachers of English - NTCE.

Nassaji, H. (2003). Higher-Level and Lower-Level Text Processing Skills in Advanced ESL REading Comprehension. The Modern Language Journal, 261-276.

Nation, I. (2001). Learning vocabulary in another language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

OECD. (2011). Education at a Glance 2011. OECD Publishing.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 54-67.

Sahbaz, N. K. (2012). Evaluation of reading attitudes of 8th grade students in primary education according to various variables. Educational Research and Reviews Vol. 7(26), 571-576.

Selvi, A. F. (2011). World Englishes in the Turkish sociolinguistic context. World Englishes, vol. 30, no. 2, 182-199.

Shankweiler, D., & Crain, S. (1986). Syntactic Complexity and Reading Acquisition. Hillsdale, NJ: Haskins Laboratories.

Shiotsu, T., & Weir, C. (2007). The relative significance of syntactic knowledge and vocabulary breadth in the prediction of reading comprehension test performance. Language Testing, 99–128.

Stein, C., Cairns, H., & Zurif, E. (1984). Sentence comprehension limitations related to syntactic deficits in reading-disabled children. Applied Psycholinguistics, 305-322.

United Nations Statistics Division. (2012, July 2). Millenium Development Goals Indicators. Retrieved from United Nations Statistics Division:

http://unstats.un.org/unsd/mdg/SeriesDetail.aspx?srid=656

Wang, J., & Guthrie, J. (2004). Modeling the effects of intrinsic motivation, amount of reading, and past acheivement on text comprehension between U.S. and Chinese students. Reading Research Quarterly, 162-186.

Wigfeild, A., & Guthrie, J. T. (1997). Relations of Children's Motivation for Reading to the Amount and Breadth of Their Reading. Journal of Educational Psychology 89:3, 420-432.

Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Expectancy–Value Theory of Achievement Motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 68-81.

Yano, Y., Long, M. H., & Ross, S. (1994). The Effects of Simplified and Elaborated Texts on Foreign Language Reading Comprehension. Language Learning, 189-219.

Zimmerman, C. B. (2008). Word Knowledge: A vocabulary teacher's handbook. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Please check the CLIL for Secondary Teachers course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the How the Motivate your Students course at Pilgrims website.

|