Task-based Language Teaching: An Overview

Gizem Korkmaz, Turkey

Gizem Korkmaz is an instructor at Gediz University. She is also currently studying on an MA course in ELT. E-mail: gizem.yesil@gediz.edu.tr

Menu

What is Task-based Language Teaching?

Theory of language

Theory of learning

Types of learning and teaching activities

The structural framework of TBL

Advantages of TBL

Conclusion

References

Task-Based Language Teaching (TBLT) refers to an approach based on the use of tasks as the core unit of planning and instruction in language teaching. Some of its proponents (e.g., Willis) present it as a logical development of Communicative Language Teaching since it draws on several principles that formed part of the communicative language teaching movement from the 1980s. For example:

- Activities that involve real communication are essential for language learning.

- Activities in which language is used for carrying out meaningful tasks promote learning.

- Language that is meaningful to the learner supports the learning process.( Richards & Rodgers, 2001: 223)

According to Rod Ellis, a task has four main characteristics:

- A task involves a primary focus on (pragmatic) meaning.

- A task has some kind of ‘gap’ (Prabhu identified the three main types as information gap, reasoning gap, and opinion gap).

- The participants choose the linguistic resources needed to complete the task.

- A task has a clearly defined, non-linguistic outcome.

(Task-Based Language Learning, 2013)

Task based learning is a different way to teach languages. It can help the student by placing her in a situation like in the real world; a situation where oral communication is essential for doing a specific task. Task based learning has the advantage of getting the student to use her skills at her current level to help develop language through its use. It has the advantage of getting the focus of the student toward achieving a goal where language becomes a tool. (Task-Based Learning Pools-m)

The key assumptions of task-based instruction are summarized by Feez (1998:17 ) as:

- The focus is on process rather than product.

- Basic elements are purposeful activities and tasks that emphasize communication and meaning.

- Learners learn language by interacting communicatively and purposefully while engaged in the activities and tasks.

- Activities and tasks can be either: those that learners might need to achieve in real life; or those that have pedagogical purpose specific to the classroom.

- Activities and tasks of a task-based syllabus are sequenced according to difficulty.

- The difficulty of a task depends on a range of factors including the previous experience of the learner, the complexity of the task, the language required to undertake the task, and the degree to support available.

One clear purpose of choosing TBL is to increase learner activity; TBL is concerned with learner and not teacher activity and it lies on the teacher to produce and supply different tasks which will give the learner the opportunity to experiment spontaneously, individually and originally with the foreign language. Each task will provide the learner with new per¬sonal experience with the foreign language and at this point the teacher has a very impor¬tant part to play. He or she must take the responsibility of the consciousness raising process, which must follow the experimenting task activities. The consciousness raising part of the TBL method is a crucial for the success of TBL, it is here that the teacher must help learners to recognize differences and similarities, help them to “correct, clarify and deepen” their perceptions of the foreign language. (Michael Lewis 15). All in all, TBL is language learning by doing. (Task-Based Learning Pools-m).

Another goal of the designer and teacher is to motivate learners by selecting proper topics and tasks, improve their language awareness, present a suitable degree of challenge and engage their attention as efficiently as possible. All tasks should also have an outcome. It is the challenge of achieving the outcome that makes TBL attractive and motivating for learners. To achieve the outcome, the students should be first focusing on meaning and then on the best ways to express it in a meaningful way (Willis, 1996)

Language is primarily a means of making meaning.

Richard and Rodgers (2001) state that in common with other realizations of communicative language teaching, TBLT emphasizes the central role of meaning in language use.

Multiple models of language inform TBL.

Structural, functional, and interactional models of language are emphasized by advocates of task-based instruction. (Richards & Rodgers 2001:226)

Lexical units are central in language use and language learning.

Recently, teaching vocabulary plays a more central role in second language teaching than was once believed. Vocabulary is here used to include the consideration of lexical phrases, sentence stems, prefabricated routines, and collocations.( Richards&Rodgers 2001:227)

Conversation is the central focus of language and the keystone of language acquisition.

In TBI, speaking and trying to communicate with others using the learner’s linguistic and communicative resources is believed as the basis point. Therefore, the majority of tasks in TBLT promote speaking. (Richards&Rodgers 2001:228)

Tasks provide both the input and output processing necessary for language acquisition.

Krashen has insisted that comprehensible input is the one necessary criterion for successful language acquisition. Tasks, therefore, are believed to foster of negotiation, modification, rephrasing, and experimentation that are at the heart of second language learning.

Task activity and achievement are motivational.

Richards and Rodgers (2001) state that tasks are also said to improve learner motivation and therefore promote learning. This is because they require the learners to use authentic language, they have well-defined dimensions and closure, they are varied in format and operation, they involve partnership and collaboration.

Learning difficulty can be negotiated and fine-tuned for particular pedagogical purposes.

For Prabhu, a task is ‘an activity which requires learners to arrive at an outcome from given information through some process of thought, and which allows teachers to control and regulate that process’ (Prabhu 1987:17). Crookes defines a task as ‘ a piece of work or an activity, usually with a specified objective, undertaken as part of an educational course, at work, or used to elicit data for research’ ( Crookes 1986:1).

Willis proposes (1996) six task types built on more or less traditional knowledge hierarchies. She labels her task examples as follows:

Six types of task

- Listing: It may seem unimaginative, but in reality, it promotes a lot of talk among learners. The processes involved are: brainstorming and fact finding. The outcome a completed task or just a mind map.

- Ordering and sorting: These tasks involve four main processes: sequencing items, actions and events, ranking items, categorizing items, and classifying items.

- Comparing: These tasks involve comparing information from different resources or versions. The purpose here is to identify common points or differences. The processes involved are: matching, finding similarities and finding differences.

- Problem solving: These kind of tasks are demanding and challenging as they require intellectual and reasoning power.

- Sharing personal experiences: these tasks encourage learners to talk more freely about themselves and share their experiences with others.

- Creative tasks: These are often called projects and involve pairs or groups of learners in some kind of creative work. They also have more stages than other tasks have.

They involve the combination of other task types. Here, cooperational skills and team-work are important to achieve the tasks given.( Willis, 1996)

Pica, Kanagy, and Falodun (1993) classify tasks according to the type of interaction that occurs in task accomplishment and give the following classification:

- Jigsaw tasks: These involve learners combining different pieces of information to form a whole.

- Information-gap tasks: One student or group of students has one set of information and another student or group has a complementary set of information. They must negotiate and find out what the other party’s information is in order to complete an activity.

- Problem-solving tasks: Students are given a problem and a set of information. They must arrive at a solution to the problem. There is generally a single resolution of the outcome.

- Decision-making tasks: Students are given a problem for which there are a number of possible outcomes and they must choose one through negotiation and discussion.

- Opinion exchange tasks: Learners engage in discussion and exchange of ideas. They do not need to reach agreement.

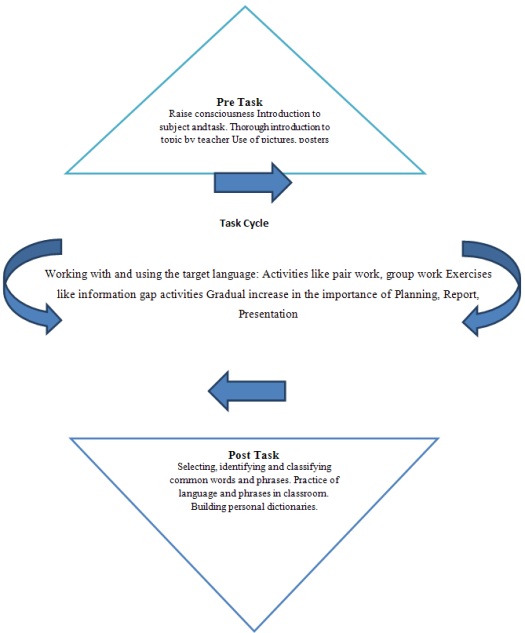

Jane Willis (1996), in her book ‘A Framework for Task-Based Learning’, outlines a third model for organizing lessons. While this is not a radical departure from TTT, it does present a model that is based on sound theoretical foundations and one which takes account of the need for authentic communication. Task-based learning (TBL) is typically based on three stages. The first of these is the pre-task stage, during which the teacher introduces and defines the topic and the learners engage in activities that either help them to recall words and phrases that will be useful during the performance of the main task or to learn new words and phrases that are essential to the task. This stage is followed by what Willis calls the "task cycle". Here the learners perform the task (typically a reading or listening exercise or a problem-solving exercise) in pairs or small groups. They then prepare a report for the whole class on how they did the task and what conclusions they reached. Finally, they present their findings to the class in spoken or written form. The final stage is the language focus stage, during which specific language features from the task and highlighted and worked on. Feedback on the learners’ performance at the reporting stage may also be appropriate at this point.

The pre-task phase introduces the class to the topic and the task, activating topic-related words and phrases. (Task-Based Learning Pools-m). This phase is usually be the shortest stage in the framework. Pre-task activities should actively involve all learners, give them relevant exposure, and, above all, create interesting doing a task on this topic. (Willis,1996:43)

Pre-task language activities:

- Classifying words and phrases

- Odd one out

- Memory challenge

- Brainstorming and mind-maps

- Thinking of questions to ask

- Teacher recounting a similar experience ( Willis,1996:43-44)

The task cycle offers learners the chance to use whatever language they already know in order to carry out the task, and then to improve the language, under teacher guidance, while planning their reports of the task. In the task stage the students complete the task in pairs and the teacher listens to the dialogues. Then the teacher helps to correct the com¬pleted tasks in oral or written form. One of the pairs performs their dialogue in front of the class and once the task has been completed the students will hear the native speaking teachers repeat the same dialogue so they can compare it with their own. (Task-Based Learning Pools-m).

The last phase in the framework, language focus, allows a closer study of some of the spe¬cific features occurring in the language used during the task cycle. (Task-Based Learning Pools-m). Analysis: Teacher sets some language-focused tasks, based on the texts students have read or on the transcripts of the recordings they have heard. Teacher starts Ss off, then Ss continue, often in pairs. Teacher goes round to help; Ss can ask individual questions.( Willis & Willis, 1996:57) Practice: Teacher conducts practice activities as needed, based on the language analysis work already on the board, or using examples from the text or transcript. Practice activities can include: choral repetition, memory challenge games, sentence completion, matching the past tense verbs, dictionary reference. (Willis & Willis, 1996:57-58)

Optional follow-up: At the end of the task-based framework, students could: repeat the same or a similar oral task but with different partners, go back through the task materials or earlier texts and write down in their notebooks useful words, discuss how they felt about the task and the task cycle. (Willis & Willis, 1996:58)

Willis (1996) states that from the learner’s position, doing a task in pairs or groups has a number of advantages. Bearing them in mind will also guide you in your role as facilitator of learning.

- It gives learners confidence to try out whatever language they know, or think they know, in the relative privacy of a pair or small group, without fear of being corrected in front of the class.

- It gives learners experience of spontaneous interaction, which involves composing what they want to say in real time, formulating phrases and units of meaning, while listening to what is being said.

- It gives learners a chance to benefit from noticing how others express similar meanings. Research shows they are more likely to provide corrective feedback to each other (when encouraged to do so) than adopt each other’s errors.

- It gives all learners chances to practice negotiating turns to speak, initiating as well as responding to questions, and reacting to other’s contributions (whereas in teacher-led interaction, they only have a responding role).

- It engages learners in using language purposefully and cooperatively, concentrating on building meaning, not just using language for display purposes.

- It makes learners participate in a completed interaction, not just one-off sentences. Negotiating openings and closings, new stages or changes of direction are their responsibility. It is likely that discourse skills such as these can only be acquired through interaction.

Teacher’s roles

In TBL lessons, the teacher is generally a ‘facilitator’, always keeping the key conditions or learning in mind. Facilitating learning involves balancing the amount of exposure and use of language, and ensuring they are both of suitable quality.

In a TBL class, the emphasis is given on what learners are doing, often in groups or pairs. The teacher is involved in setting tasks up, ensuring that learners understand and get on with them and drawing them to a close. Although learners do tasks independently, the teacher still has overall control and the power to stop everything if necessary.

The part the teacher plays during each component of the task framework also varies according to its aim. At the end of the framework, where the focus turns to language form, the teacher acts as ‘language guide’

In a broader sense, the teacher is also the course guide, explaining to learners the overall objectives of the course and how the components of the task framework can achieve these. A summing up of what they have achieved during a lesson, or after a series of lessons, can help learners’ motivation. (Willis, 1996:40-41)

Learners’ roles

A number of specific roles for learners are assumed in current proposals for TBI. The main role of the learners in a task-based classroom is group participant. Many tasks will be done in pairs or small groups. For some students that are accustomed to whole-class or individual work, this may require some time and adaptation.

In TBL classes the learners also monitor the things that are going on in class. Tasks are not employed for their own sake but as a means of facilitating learning. Class activities should be suitable for students to notice how language is used in communication. Learners need to attend not only to the message but also to the form.

Learners in TBL classes should also be a risk-taker and innovator. Practice in restating, paraphrasing, using paralinguistic signals, and so on, will often be needed. The skills of guessing from linguistic and contextual clues, asking for clarification , and consulting with other learners may also be need to be developed.

TBL offers a structured approach to learning, and supports the notion that learning occurs most effectively when related to the real-life tasks undertaken by an individual. TBL encourages the development of the reflective learner, and accommodates a wide range of learning styles. TBL offers an attractive combination of pragmatism and idealism: pragmatism in the sense that learning with an explicit sense of purpose is an important source of student motivation and satisfaction; idealism in that it is consistent with current theories of education. (Simpson)

Task-based language teaching challenges mainstream views about language teaching in that it is based on the principle that language learning will progress most successfully if teaching aims simply to create contexts in which the learner’s natural language learning capacity can be nurtured rather than making a systematic attempt to teach the language bit by bit. (Ellis 2009:222)

For Freeman (2011) there is no contradiction in saying this and at the same time saying that TBLT can also be complemented by explicit instruction in grammar and vocabulary.

Crookes G. 1986 Task Clarification: A Cross-Disciplinary Review. Technical Report No. 4. Honolulu: Center for Second Language Classroom Research.

Ellis R. (2009). ‘Task-based language teaching: Sorting out the misunderstandings’ International Journal of Applied Linguistics 19/3:221-46.

Feez S. (1988). Text-Based Syllabus Design. Sydney: National Centre for English Teaching and Research

Prabhu, N. S. 1987. Second Language Pedagogy. Oxford University Press

Richards J. & Rodgers T. S. (2001). Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching (2nd. edition). United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Willis J., (1996) A framework for Task Based Learning Italy: Longman

Willis J, and Willis D. (eds.)1996. Challenge and Change in Language Teaching Oxford: Heinemann.

Task Based Language Learning 28th December 2013 retrieved from

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Task-based_language_learning

Task Based Learning 28th December 2013 retrieved from:

www.languages.dk/archive/pools-m/manuals/final/taskuk.pdf

A Simpson - Developing Teachers., 2008 - retrieved from: etu.isfedu.org

Please check the How the Motivate your Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Creative Methodology for the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

|