Ways of Expressing Inducement In Classroom Language: Comparison Between Bulgarian and English

Petranka Ruseva, Bulgaria

Petranka Ruseva works at College-Dobrich, Konstantin Preslavsky University of Shumen, Bulgaria, where she has been teaching English since 2001. Her research interests are in linguistics, methodology, and recently in the application of corpus linguistics in English language teaching. E-mail: petranka.ruseva@shu.bg

Menu

Introduction

Classroom language directives in English

Classroom language directives in Bulgarian

Conclusions

References

The more the foreign language is used in language classroom, the greater the opportunity for the students to learn it and consider imperatives as a part of real communication. Therefore, it is crucial to the success of the students who are future teachers that they are taught a variety of possible ways to organize what is happening in the classroom and direct the students appropriately. The corpus of language material, which serves as a basis for the research, concerns Bulgarian structures and English structures both used in classroom during the internship of future teachers. The comparison between the Bulgarian language in the classroom and the English language in English language classes by the same college students gives ideas about the way to expand the range of structures in foreign language classes as there is a parallel between the two languages. This is a circumstance that could facilitate the use of foreign language structures (English) as they are really close to the familiar structures of the mother tongue (Bulgarian) of the future teachers. There are a lot of means of achieving almost one and the same result of directing the students to bring out the necessary actions but the focus here is only on some of them. In English it concerns first of all the most often used structures, i.e. the imperative ones. Other indisputably widespread structures are the polite requests that follow the pattern Can you + verb? Schmidt (1994, p. 5) draws the two closer arguing that “[i]nfact, many ESL learners are taught to add “please” and modals “can/could/will/would +you” to imperatives in making polite requests”. According to Simon-Vandenbergen and Taverniers (2010, p. 172) „‘Can you…?’ may have the conventional meaning of a casual command” Also, it is argued that second person declaratives with can/must/will can suit the purpose. Belyaeva (1990, pp. 5, 6, 22) considers interrogative and declarative constructions with can, must and will as means of expressing directive speech acts. As Hornby (1976, p. 195) puts it “[m]ust is the most usual verb in spoken English for orders and prohibitions”. Huddleston and Pullum (2005, p. 172) call the “closed interrogatives” used for requests (Will you feed the cat.) and some declaratives (You will drive her to the airport and then report back to me.) non-imperative directives.

The corresponding structures in Bulgarian are also appropriate for expressing inducement in classroom language. In the Bulgarian language the inflected second person form and the complex forms made by means of the verbal particle neka (Boyadzhiev et al. 1999, Chakarova 2009) are recognized as the usual way for using an imperative. But interrogatives with „moga, ne moga in present” (can, can’t in present) (Kirova and Vaseva 1995) can also express inducement. “[A] modal word +da-form” can be used as a lexical expression of an imperative meaning and tryabva is among these modal words (Kirova and Vaseva 1995, pp. 267-268, p. 270). Kirova and Vaseva (1995, p. 222) point out some indicative forms in present and future but emphasize that the ones in future are used more often „Ti shte otidesh (=iskam da otidesh, idi)” (You will go now (=I want you to go now, go)). The authors quoted above argue that these forms state an explicit demand, i.e. an order directed to a person of a lower status. This makes the structures appropriate to be used in classroom language considering teacher – student relationship.

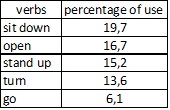

The material gathered from 28 lessons in English language classes in a Bulgarian primary school used by Bulgarian students during their internship as future teachers composes the corpus that is used for the research. The tapes are transcribed and the data is processed. The results show that the only structure that college students dare to use in the classes in order to direct their students during the lessons is the imperative. Not surprisingly, most of the imperatives are in a positive form. Only 1,5% of the imperatives are in negative. The five most common verbs in imperative are shown in Table1.

Table 1. Five of the most common English verbs in imperative in classroom language corpus

The rules in the classroom necessitate the everyday use of stand up and sit down. As students are familiar with these rules, they are less often asked to stand up as compared to being allowed to sit down. They are sometimes accompanied by please as in (1) where C stands for corpus and is followed by a number corresponding to the number of the example in the corpus.

(1) C_9 Sit down, please!

The verb open is usually used by the teachers in their attempt to direct the students in the activity that follows, e.g. (2).

(2) C_19 Open your Students’ books at page 75.

The rest of the verbs are used in various circumstances but in all cases they are used as directives.

Only 1,5% of all the English imperatives in the corpus are in negative. (3) is an example of a negative imperative from the corpus.

(3) C_33 Don’t touch them.

It expresses a prohibition very clearly while the positive imperatives are often ambiguous between a command and an instruction. But words such as now and then help to identify the clauses as instructions, see (4).

(4) C_47 Read then draw the line.

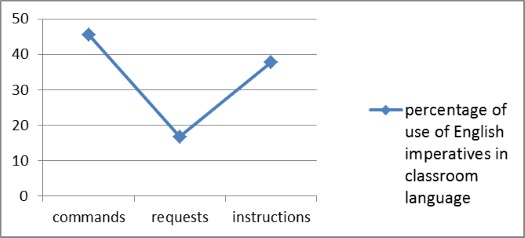

Fig.1. Use of English imperatives in the corpus of classroom language

Although it is true what Peters (1949, pp. 535-536) observes, i.e. that “[w]e do not use imperative sentences solely to command” and there are “other uses, e.g. to advise, exhort, request, entreat, instruct, direct, etc.”, Fig.1. presents the predominance of commands and instructions over requests and the lack of other uses in this particular corpus.

The language used by the same students in the same number of lessons is considered in terms of Bulgarian imperative structures. Altogether the directives present 23% of all the clauses in the corpus. As expected, most of the imperatives in Bulgarian are in positive form but the percentage is a bit lower than that in English in the corpus. Here the negative examples come up to 2,5% of all directives in the corpus. Several structures are paid attention to with regard to this, i.e. imperative forms with the negative particle ne; the use of the imperative particle nedey, the modal verb mozhe, and the use of stiga.

(5) C_638 Ne zadavayte vaprosi kam nikogo. (Don’t ask anyone.)

(6) C_1262 Nedey sega da gi broish. (Don’t count them now.)

(7) C_1233 Ne mozhe tseliya chas samo da otsvetyavate. (You cannot colour your paintings all class long.)

(8) C_722 Stiga shtraka s tozi himikal. (Stop clicking the pen = Don’t click the pen.)

As all these last-year students in their role of teachers are Bulgarian, they feel more comfortable in using the language in an appropriate manner and this results in a greater variety of forms as compared to the single structure they use in the foreign language. The imperative structure occurs most often and it comprises 13,8% of all directive forms that are recognized in the language material.

(9) C_188 Zapishete si. (Write it down.)

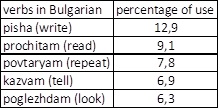

The top five of the most common verbs in Bulgarian in the corpus are listed in Table 2.

Table 2. Five of the most common Bulgarian verbs in imperative in classroom language corpus

All of the verbs are typical for classroom language especially for teaching a foreign language at a primary school where repetition of new words, reading, and writing is necessary.

In addition to the most often used structure the corpus gives some lexical modifiers of imperativeness in the modern Bulgarian language such as hayde, davay, ya. As Chakarova (2009, p. 113) points out, they achieve the effect of colloquialness and spontaneity. In 88% percent of the cases hayde is used as an encouragement, as an attempt to urge the students to be bolder and start doing the task.

(10) C_97 Hayde. Povtorete. (Come on. Repeat it.)

Much rarer hayde is used in a way quite similar to let’s structure. The way let’s includes the person who is speaking in carrying out the action together with the person to whom the words are addressed, this same way hayde is followed by a verb in 2 person plural.

(11) C_1300 Hayde da si povtorim otnovo novite dumi. (Let’s repeat the new words again.)

As Chakarova (2009, p. 132, p. 143) points out davay can be used as a delexicalized verb. This way the distance between the people in the act of communicating is shortened.

(12) C_492 Davay, Rache. (Come on, Rache, i.e. read it (in this context).)

Ya is used in a collocation with an imperative grammatical form and the former adds to the semantics of the latter (Chakarova, 2009, p. 112).

(13) Ya chakay da go vzemem i da go pokazhem na vsichki. (similar to Let me take it and show it to everyone but the authority belongs to the speaker and he/she does not ask for a permission but it rather serves as a suggestion).

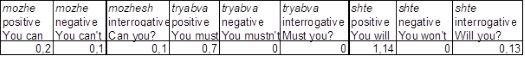

The possibilities that the modal verbs offer in the English language are offered in the Bulgarian language as well. Although much more rarely as compared to the imperative structures, most of them do occur in the corpus as shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Percentage of directives with mozhe/ tryabva/ shte (can/ must/will) used in the corpus

As it is observed in English, you can can express permission granted by an authority (Simon-Vandenbergen and Taverniers, 2010, p.171). Quite similar is the situation with its equivalent in Bulgarian, i.e. mozhe(sh).

(14) C_136 Mozhete da si pomagate, no s uchebnika. (You are not allowed to help each other but you can use the textbook.)

Although even smaller in number, negatives and interrogatives are also present in the corpus. In addition to the most common structure of a negative particle followed by modal verb, there is another structure constructed the other way round, i.e. first the modal verb and then the negative particle:

(15) C_1255 Mozhe da ne se razhozhdash (hinting that as a rule strolling in the classroom is not allowed during the lesson).

As it is in English, interrogatives in Bulgarian are more like polite requests:

(16) C_1238 Mozhesh li pak da povtorish (Can you say it again? where the teacher has no doubts that the student can do the action and he/she is not questioning the ability but is rather requesting).

The most rarely used one of the three modal verbs is tryabva. It occurs only in positive clauses. As must in English, tryabva implies the authority of the speaker.

(17) C_248 Tryabva da svarzhete izrecheniayata s kartinkite (You must match the sentences and the pictures).

A bit more complex is the use of shte followed by tryabva (= you will have to).

(18) C_177 ( Az shte vi zadam vypros, a vie shte tryabva da mi otgovorite. (I will ask you a question and you will have to answer it.)

Just like will in English, shte in positive declaratives and in interrogatives in Bulgarian is used to express a command. Interrogatives sound more polite in both languages, though.

(19) C_135 Vie shte se opitate da mi otgovorite na angliyski ezik. (You will try to answer in English.)

(20) C_358 Gabi, shte gi prochetesh li? (Gabi, will you read them?)

All of these different types of clauses are used to direct students in bringing out a particular action but it is difficult to decide exactly what they convey. Several types are identified in the corpus, i.e. commands, prohibitions, advice, requests, warnings, suggestions, permissions/concession and instructions. Sometimes it is quite embarrassing to decide between two, or even more possibilities. For example (20) might be a command but it also can be permission as it often happens children to raise their hands impatiently jumping around in their eagerness to answer the question.

(21) C_139 Kazhi, Dobcho. (Answer the question, Dobcho.)

In a similar way (21) can be advice or permission.

(22) C_141 Pomogni si s uchebnika. (Use the textbook as a prompt.)

But most troublesome of all seems the task to decide whether it is a command or an instruction. For example in (22) the teacher gives a command to the student to say the sentence but since the way it is expected to be said is specified, it might be understood as an instruction.

(23) C_1184 Kazhi go na angliyski. (Say it in English.)

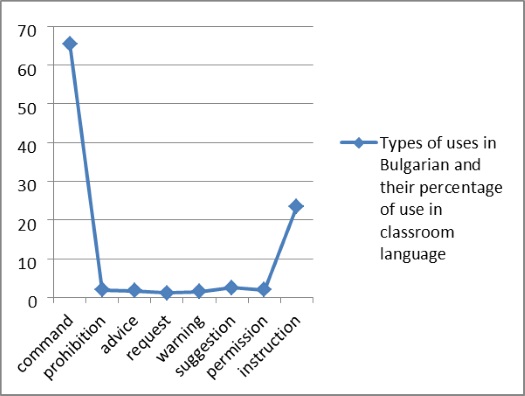

Despite the difficulties to identify precisely what each of the examples convey, commands outnumber the rest of the types. Next come the instructions and the least in number is the occurrence of requests. Fig 2. exhibits the percentage of use of all the types in the corpus.

Fig. 2. Directive uses of Bulgarian in the corpus of classroom language

Although prohibitions, advice, warnings, suggestions and permissions are conveyed by means of the structures mentioned above, their number is insignificant compared to the large portion of instructions and especially commands.

The corpus lacks the variety of types of structures used for directives that the English language offers. It might be due to the fact that English is a foreign language to these teachers since the structures in their mother tongue show greater diversity in terms of use.

According to the data results of the research several conclusions can be drawn:

- The most common verbs are different in Bulgarian and in English. Whereas in English they concern classroom rules, in Bulgarian they are directed mostly to the process of work closely related to language learning.

- As what concerns directives, the imperative structure is the only structure in English used in the corpus, while in their mother tongue future teachers feel more at ease to use different structures such as declaratives with can/must/will as well as interrogatives with can and will.

- In both languages positive clauses are much more preferable.

- As English is known for the polite use of please, it affects the use of imperatives in classroom language and the number of requests used in English is greater than their number in Bulgarian.

- As regards the corpus, commands and instructions are the most common types in both languages.

The literature review confirms that in addition to the well-known imperative form English allows the use of other structures that express inducement. Therefore, it is advisable to help future teachers expand the range of structures used in order to direct schoolchildren during the lessons. This would not be a difficult task as the interference of the mother tongue could have a positive impact but it is necessary to draw their attention to the topic first.

Belyaeva, E. I. (1990). Functionalno-tipologicheskie aspektyi analiza imperativa. Chast 1 Grammatika I tipologiya povelitelnyih predlozhenii. Moskva: Akademiya nauk USSR Institut yazikoznaniya.

Boyadzhiev, T., Kutsarov, I., & Penchev, Y. (1999). Savremenen balgarski ezik. Boyadzhiev, T. (ed.), Sofia: Petar Beron.

Chakarova, K. (2009). Imperativat v savremenniya balgarski ezik. Plovdiv: Pigmalion.

Hornby, A. S. (1976). Guide to Patterns and Usage in English. Second edition, Printed in Hong Kong: Sing Cheong Printing Co., Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Huddleston, R., & Pullum, G. K. (2005). A Student’s Introduction to English Grammar. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kirova, Т., & Vaseva, I. (1995) Izrazyavane na podbuditelnost v ruski I balgarski ezik. In: Sofia University proceedings . Faculty of Slavonic philologies. Ezikoznanie, vol. 88, kn.1, pp. 155-219.

Peters, A. F. (1949). R. M. Hare on Imperative Sentences: A Criticism. Mind, New Series, vol. 58, No. 232, October 1949, Oxford University Press, pp. 535-540.

Schmidt, T. Y. (1994). Authenticity in ESL: A Study of Requests. Master thesis. Southern Illinois University, pp. 5-53.

Simon-Vandenbergen, A., & Taverniers, M. (2010). English Grammatical Usage: A study guide. Leuven: Acco.

Please check the Practical uses of Technology in the English Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

|