EFL Acquisition at University via Real-Life Input

Milka Hadjikoteva, Bulgaria

Milka Hadjikoteva, PhD, a senior assistant professor is currently the Head of English Studies Department at New Bulgarian University, Sofia, Bulgaria. She teaches linguistic disciplines, teacher training courses as well as EFL and ESP courses. Ms. Hadjikoteva’s research interests lie in linguistics, semiotics, translation studies, methodology and approaches to EFL teaching. She is also active as a translator of fiction and philosophy. E-mail: mhadjikoteva@nbu.bg

Menu

Introduction

Background

A task developed and launched

Conclusion

References

Since the introduction of the Natural Approach and the Task-Based Approach in 1980s, it has been viewed that the primary purpose of using a foreign language is to communicate meanings and messages. The former theory suggests that after a “silent period” each student begins using the foreign language in a natural way based on the premises of universal grammar principles. It is the role of the teacher to provide sufficient input, to lower the affective filter and to facilitate acquisition through developing basic interpersonal communicative skills. The latter stresses the importance of the communicative nature of tasks. Although the main focus is on authenticity and meaning, grammar is not devoid of significance. Based on the premises of these two approaches, the article discusses a particular task which provides comprehensible input, an anxiety-free environment, and meaningful communication through developing the four skills and transferring the initiative and responsibility to students.

Whether a foreign language is claimed to be acquired or learned, it takes a continuous effort to master it. The difference between acquisition and learning has been introduced by Stephen Krashen in his model for second language acquisition and since then acquisition of a second language has been regarded as a subconscious process or “implicit learning, informal learning, and natural learning”, “picking-up” a language (Krashen, 1982: 10), whereas learning results from a conscious process.

“… the term “learning” … refers to conscious knowledge of a second language, knowing the rules, being aware of them, and being able to talk about them. In non-technical terms, learning is “knowing about” a language, known to most people as “grammar”, or “rules”. Some synonyms include formal knowledge of a language, or explicit learning.” (Krashen, 1982: 10)

Krashen argues that acquired knowledge takes precedence over learnt knowledge. However, according to him learnt language cannot be converted into acquired:

“A very important point that also needs to be stated is that learning does not “turn into” acquisition. The idea that we first learn a new rule, and eventually, through practice, acquire it, is widespread and may seem to some people to be intuitively obvious.” (Krashen 1982: 83).

Krashen’s model describes the difference between learning and acquiring a second language and explains the factors aiding or preventing acquisition.

“The important question is: How do we acquire language? If the Monitor hypothesis is correct, that acquisition is central and learning more peripheral, then the goal of our pedagogy should be to encourage acquisition. The question of how we acquire then becomes crucial.” (Krashen 1982:20).

According to the model developed by Krashen (1981, 1982) it is the input that explains certain factors which influence foreign language acquisition. It is suggested that in order to prompt acquisition the amount of the language input should be a little beyond the learner’s current level of comprehension. (Krashen, Long, Scarcella (1979) - ‘i+1’ (input + 1)

“We acquire language in an amazingly simple way – when we understand messages. We have tried everything else – learning grammar rules, memorizing vocabulary, using expensive machinery, forms of group therapy etc. What has escaped us all these years, however, is the one essential ingredient: comprehensible input.” (Krashen 1985: vii).

At the time when Stephen Krashen’s “input hypothesis” gained popularity, Merrill Swain’s ‘output hypothesis’ (1985) was introduced. It claims that opportunities should be created to produce and practice spoken and written language, emphasizing linguistic accuracy. According to her it is only when students have to produce meaning in the foreign language that they pay attention how the language is used. Moreover, they find out what they are supposed to know in order to convey meaning. Thus a consolidation of the existing knowledge takes place and the need for further practice is realized. As a result, production does not only enhance fluency, but also creates awareness of gaps in the existing knowledge.

Both input and output are important in foreign language acquisition, however the role of the social factor is of utmost importance as well. Swain (1998, 2005) claims that through collaborative dialogue students are encouraged not only to experiment but to obtain important feedback on their performance and in turn further effort is encouraged. Getting used to work in a team, students usually overcome easier the anxiety caused by the presence of an affective filter used by Krashen in his model. The concept of an affective filter has not been invented by Krashen himself. It was introduced by Dulay and Burt in 1977 (Krashen 1981: 31). However, the concept of a number of affective factors important when acquiring a second language is central to his model. The Affective Filter hypothesis attempts to explain the relationship between certain affective variables, i.e. motivation, self-confidence and anxiety, and acquisition of a second language. The claim is that when the level of the affective filter is high, the acquisition is prevented. When the affective filter is low, it is possible to comprehend the input.

“The Affective Filter hypothesis captures the relationship between affective variables and the process of second language acquisition by positing that acquirers vary with respect to the strength or level of their Affective Filters. Those whose attitudes are not optimal for second language acquisition will not only tend to seek less input, but they will also have a high or strong Affective Filter – even if they understand the message, the input will not reach the part of the brain responsible for language acquisition, or the language acquisition device. Those with attitudes more conducive to second language acquisition will not only seek and obtain more input, they will also have a lower or weaker filter. They will be more open to the input, and it will strike “deeper”.” (Krashen 1982: 31)

The affective variable emphasized by Krashen is anxiety. “There appears to be a consistent relationship between various forms of anxiety and language proficiency in all situations, formal and informal. Anxiety levels may thus be a very potent influence on the affective filter” (Krashen 1981: 29).

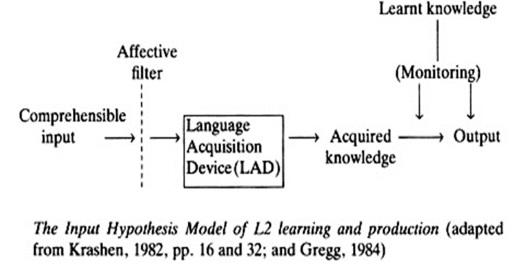

The figure below shows the Monitor Model suggested by Krashen.

The hypotheses in the model suggest how to achieve optimal acquisition while mastering a foreign language and define the variables which have a negative impact on it. According to Krashen, anxiety is the most significant variable.

“The input hypothesis and the concept of the Affective Filter define the language teacher in a new way. The effective language teacher is someone who can provide input and help make it comprehensible in a low anxiety situation“ (Krashen 1982: 32).

Since the introduction of the Affective Filter hypothesis, a number of researchers have contributed to define types of language anxiety and their impact on second language acquisition.

Gardner (1985) claims that it is “a construct of anxiety which is not general but instead is specific to the language acquisition context” (Gardner 1985:34). Based on his research Horowitz and Cope (1986) introduce the term Foreign Language Anxiety (FLA). According to them FLA is a situation-specific anxiety. Moreover, it is claimed that high levels of FLA may have a negative impact on students, their self-esteem and second language acquisition. In order to measure FLA, a Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale (FLCAS) was developed. Horowitz and Cope (1986) identified a number of other situation-specific anxieties related to FLA, such as communication apprehension (CA), fear of negative evaluation (FNE) and test anxiety (TA).

The notion of “communication apprehension” was introduced by McCroskey (1977), defined as “an individual’s level of fear or anxiety associated with either real or anticipated communication with another person or persons” (Morreale, 2010:78). According to the researchers, communication apprehension may be encountered in interpersonal communication, in communication in meetings, in group communication and in public speaking. There is also research on communication apprehension experienced by non-native English speakers. Yung and McCroskey (2004) published the results of their study of bilinguals in the United States, showing the high level of apprehension in the non-native English speaking students in public speaking situations when they have to communicate in English. For instance, academic presentations may be regarded as a challenge to both university students and teachers due to, among other factors, to the specific nature of communication apprehension (Hadjikoteva, 2015).

Hilleson (1996) claims that FLA is generally experienced not only when speaking and listening, but when reading and writing as well. Other types of FLA were identified by Saito, Horowitz & Garza (1999) and a Foreign Language Reading Anxiety Scale (FLRAS) was developed. Based on a study of multilingual adults around the world, Dewaele, Petrides & Furnham (2008) suggest that low levels of FLA allow more foreign languages to be mastered. Horowitz (2010) claims that “in addition to individual characteristics, larger social circumstances such as the availability of supportive conversational partners and L2 role models may play a role in helping language learners avoid or overcome FLA” (Horowitz 2010: 166).

To sum up, anxiety is an influential factor in mastering a foreign language. “Anxiety is a psychological construct, commonly described by psychologists as a state of apprehension, a vague fear that is only indirectly associated with an object.” (Hilgard, Atkinson, & Atkinson, 1971 cited in Scovel, 1991:18). There is a different level of anxiety experienced by learners engaged in different types of communication skills in the second language, such as speaking, listening, writing and reading.

Having recognized the significance of foreign language acquisition and communication apprehension or anxiety, the issue of the relevant input becomes of utmost importance. There are no hard and fast rules to measure how much input is considered as being enough and how to decide whether it is both relevant and comprehensible. The present article is not going to discuss the correlation between different types of students and relevant input (Hadjikoteva, 2005). However, according to Krashen’s model, a second language acquisition process relies heavily on the amount of comprehensible input. As Figure 1 shows the input goes through an affective filter which based on the Affective Filter Hypothesis is “a mental block, caused by affective factors ... that prevents input from reaching the language acquisition device' (Krashen, 1985:100). Krashen uses the notion of the language acquisition device to introduce the idea of a part of the brain functioning as a programme where the parameters of the universal grammar are set. According to Chomsky universal grammar is regarded as a specific module at the base of all languages, which handles any specific language.

“It is reasonable to suppose that universal grammar determines a set of core grammars and that what is actually represented in the mind of an individual even under the idealization to a homogeneous speech community would be a core grammar with a periphery of marked elements and constructions.” (Chomsky, 1982: 8)

“Universal grammar attempts to formulate the principles that enter into the operation of the language faculty. The grammar of a particular language is an account of the state of the language faculty after it has been presented with data of experience; universal grammar is an account of the initial state of the language faculty before any experience. (Chomsky 2001: 61, 62)

It is claimed that universal grammar consists of a number of parameters set differently for different languages. In order to fit the pattern typical of the second foreign language, the comprehensible input should be familiar, however there should be some challenge for students to provoke their interest and lower the affective filter. It has been suggested that through a collaborative dialogue students are both encouraged to experiment and to make further effort. In fact, it is the collaborative dialogue that lowers the affective filter. Working on authentic tasks in collaboration have been the essential characteristics of the Task-Based Language Learning approach.

Considered one as of Communicative Language Teaching branches, the Task-Based Learning approach has become popular for developing foreign language fluency and enhancing student confidence in using it. The approach stresses the importance of engaging learning in meaningful tasks performed using the target language.

According to Prabhu (1987), who popularized task-based learning while working in Bangalore, India, the core idea of task-based learning is a linguistic action that learners are required to perform. Tasks themselves are used to trigger learners' natural mechanisms for second-language acquisition. Task-based learning has its roots in Krashen’s language acquisition hypothesis restated by Krahnke (1987) as ‘the ability to use a language is gained through exposure to and participation in using it’. Krankhe claims that task-based learning helps learners develop ‘communicative competence, including linguistic, sociolinguistic, discourse and strategic competence’. Ramirez (1995) adds to Krankhe’s theory by saying that ‘solving a linguistic task means that learning the target language will be the means to an end rather than the goal itself’. “Connecting tasks to real-life situations creates the right context for the acquisition of a language in a meaningful way and provides large amounts of input and feedback”. (Krahnke, 1987).

Ellis (2003) claims that a task should contain goals and objectives, activities, specific roles assigned to the teacher and learners as well as a setting. Tasks primarily focus on pragmatic meaning and have a clearly defined, non-linguistic outcome. The students are supposed to choose the resources needed to complete the task. Prabhu (1987) suggests that tasks include gaps, such as information gaps, reasoning gaps, and opinion gaps. One of the main characteristics of successfully formulated tasks is that by completing them, new language and/or new ways of learning are usually generated. As Neykova (2012) points out “the value of the task-based approach lies in its potential to stimulate language learners to use the target language in real life communicative situations”.

Language tasks are defined in various ways, e.g. Bygate, Skehan and Swain (2001). The major criteria imply that the most effective foreign language tasks are closely related to the real world, encourage students to summarize the references used and to produce content that resembles real-world communication. Ellis (2003) firmly supports the idea that task-based language learning is mainly designed with the objective of helping learners develop abilities that engage them successfully in language use as a means of real-life communication. Bygate (2001) claims that an isolated use of a task cannot promote learning. Neykova (2015) suggests a way of integrating various types of tasks into the process of blended learning. Thus it is the systematic integration of tasks into the teaching process that matters most.

In order to both lower the affective filter and provide comprehensible input to my students, every time I begin teaching an Intermediate group I suggest that they start regularly reading the news bulletins published in the website www.newsinlevels.com (World News for Students of English). The explanatory stage of the task is unfolded during the lesson. The news bulletin is used as an authentic source of information to set the scene for a reading comprehension activity. A few pieces of news are read, examining the definitions of the difficult words provided in a glossary following the news. In addition, a number of monolingual dictionaries available online are shown to students to encourage them to look up unfamiliar words and phrases. Then a student is asked to briefly retell some news of his/her own choice. In order to be able to develop yet another skill besides reading and speaking, the students are asked to write down a one-sentence summary of the news they are listening to. In this way they are encouraged to produce content that resembles real-life communication both in writing and orally.

Following the group work in class, the students are set a task. Their task is once a week to present a piece of news to their peers. Students are supposed first to peruse the news bulletin in their free time, and then to select, read and prepare to talk briefly about a piece of news in front of the whole group.

In the first stage of the task each speaker is allowed to show the webpage on the screen while talking about the news selected in advance and is asked to explain the unfamiliar vocabulary items to the group. The rest of the group write down one-sentence summaries of the news, reporting “who does what how where and when”. Thus, without paying special attention to the word order in English, students are implicitly made to obey the grammatical rules. At the end of each session, students type their summaries in the Forum of their e-course in the e-platform Moodle used by New Bulgarian University.

Each student presents a piece of news once a week for three weeks in a row and writes down numerous one-sentence summaries of the other speakers’ news. At first some of the students are anxious and embarrassed to talk to their peers. Gradually, however, they feel more and more confident and they start overcoming their anxiety.

When students start feeling at ease with the first stage of the task, they are introduced to the second stage. Each student talks about a piece of news of his/her own choice without showing the webpage to the group. The speakers are supposed to write down key words on the whiteboard and give their explanations in English. Due to the experience gained throughout the first stage, students feel confident enough both to talk about their pieces of news and to explain new vocabulary items to the group. As a result, students start participating more actively in discussions, since they are expected to write a one-sentence summary of each of the news listened to without actually having access to the webpage.

In my opinion, the task utilizes and exemplifies the potential systematized authentic tasks closely related to the real world. It helps learners develop abilities that allow them to use a foreign language as a meaningful tool. Such an integrated task helps learners develop all the four skills preparing them for real-life communication.

I was inspired to design the task (Hadjikoteva 2016) by professor Lilia Savova, Indiana University of Pennsylvania. In her plenary session at BETA Conference 2015 prof. Savova talked about the importance of the 20/80 principle of design, known as Pareto principle (Koch 1998), while designing FLT materials. The task applies this principle and unfolds its potential at the same time. Once a week each student makes an effort to read through a news bulletin, select a piece of news, read it carefully, look up the unfamiliar vocabulary items and prepare to talk in front of a group of students. Moreover, the individual effort is multiplied a dozen times – each week numerous students share their newly acquired knowledge with their peers. Furthermore, because students are engaged in both speaking and writing, they are supposed to master all four skills, namely, reading, writing, listening and speaking first on their own and later on together with their peers. As a result, everyone is required to use both old and new information in context a number of times, which provides meaningful and comprehensible input and an opportunity to witness the outcome, i.e. a piece of news each student has prepared to talk about is carefully listened to by a whole group of students and the information shared is used by every student to formulate a one-sentence summary.

Students are encouraged to gain enough confidence to speak in front of their peers, to write key information on the whiteboard and to explain the meaning of unfamiliar vocabulary items in context. In addition, they are motivated to monitor their grammatical rules and to notice the extent to which their peers follow the grammatical rules. The two stages of this task may be used as the initial steps in preparing university students to deliver academic presentations in English as a foreign language since the whole process of preparing an academic presentation exemplifies the 20/80 principle, i.e. preparing to talk on a particular topic furnishes the speaker with a whole set of life skills to be used in a variety of situations.

Based on the premises of the Natural Approach and the Task-Based Approach, the task discussed in this article encourages students to use English as a foreign language to communicate meanings and messages in an authentic environment. It draws on the premise that following a relatively “silent period” by adjusting and developing the skills needed to elicit key words and phrases and talk to peers, each student begins using the foreign language in a natural way obeying the grammatical rules which are reinforced in the process. The responsibility to receive sufficient input, to obliterate the affective filter and to prompt acquisition is transferred to students who feel comfortable and free to select, developing all the four skills. While the nature of the task is communicative and authentic, the significance of mastering both vocabulary and grammar in order to communicate meaningfully stands out. The task proves that students acquire a foreign language when they take the responsibility of their choices being monitored and facilitated by the teacher, while the comprehensive input is provided by the real-life resources and is transferred to a communication input due to all the personal efforts multiplied by number of these efforts following the Pareto principle.

Bygate, M., P. Skehan, and M. Swain (eds.) (2001) Researching pedagogic tasks: second language learning, teaching and testing. Harlow: Longman.

Chomsky, N. (2001). Language and Problems of Knowledge. The Managua Lectures. The MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam, 1982, Lectures on Government and Binding, Dordrecht: Foris.

Dewaele, J-M., K. V. Petrides & A. Furnham (2008). Effects of trait emotional intelligence and sociobiographical variables on communicative anxiety and foreign language anxiety among adult multilinguals: A review and empirical investigation. Language Learning 58.4, 911–960.

Ellis, R. (2003) Task-based language learning and teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gardner, R. C. (1985). Social psychology and second language learning: The role of attitudes and motivation. London: Edward Arnold.

Hadjikoteva, M. (2005). Types of Students and Relevant Input. Bulgarian English Teachers' Association (BETA), 2005

Hadjikoteva, M. (2015). Challenging academic presentations. English Studies at NBU, Vol. 1, Issue 1, pp.46-62, http://esnbu.org/index.php?wiki=vol1-issue1-2015, (retrieved April 30, 2017)

Hadjikoteva, M. (2016). Short Talks in Class. Winning entry from the BETA Competition for the prize of LILIA SAVOVA. BETA-IATEFL. file:///E:/Milka_artciles/BETA-E-Newsletter-Jan_Feb_2016.pdf (retrieved April 30, 2017)

Hilleson, M. (1996). ‘I want to talk with them, but I don’t want them to hear’: An introspective study of second language anxiety in an English-medium school. In K. M. Bailey & D. Nunan (eds.), Voices from the language classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 248–277.

Horwitz, E. K. (2010). Foreign and second language anxiety. Language Teaching. 43, 2, 154-167

Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., & Cope, J. A. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety. The Modern Language Journal, 70(2), 125-132. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/327317 (retrieved on April 30, 2017)

Koch, Richard. (1998). The 80/20 Principle: The Secret to Achieving More with Less. New York: Doubleday

Krahnke, K. (1987). Approaches to syllabus design for foreign language teaching. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Ramirez, A. G. (1995). Creating contexts for second language acquisition: Theory and methods. New York: Longman.

Krashen, S. (1981). Second language acquisition and second language learning. Oxford: Pergamon.

Krashen, S. (1982). Principles and practice in second language acquisition. Oxford: Pergamon.

Krashen, S. D. (1993). The power of reading: Insights from the research. Englewood, CO: Libraries Unlimited.

Swain, M. (1985) Communicative competence: Some roles of comprehensible input and comprehensible output in its development. In Gass, S. and Madden, C. (Eds.), Input in Second Language Acquisition, pp. 235-256. New York: Newbury House.

Krashen, S., Long, M., & Scarcella, R. (1979). Age, rate, and eventual attainment in second language acquisition. TESOL Quarterly, 13, 573-582.

Krashen, S.D; Terrell, T.D. (1983). The Natural Approach. New York: Pergamon.

Krashen, Stephen D. (1985), The Input Hypothesis: Issues and Implications, New York: Longman.

McCroskey, J. C. (1977). Classroom Consequences of communication apprehension. Communication Education, 26, 27-33.

Morreale, S (2010). The Competent Public Speaker, Peter Lang Publishing.

Neykova, M. (2012). Implementing a task-based approach in FLT, BETA-IATEFL

Neykova, M. (2015). An Action-oriented Approach to Foreign Language Acquisition in the Context of Blended Learning, Farago, Sofia [Нейкова, М. (2015). Дейностно-ориентиран подход към изучаването на чужд език в контекста на електронното обучение от смесен тип. София, Фараго]

Prabhu, N. S. 1987. Second Language Pedagogy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Saito, Y., E. K. Horwitz & T. J. Garza (1999). Foreign language reading anxiety. The Modern Language Journal 83.2, 202–218.

Scovel, T. (1991) The Effect of Affect on Foreign Language Learning: A Review of the Anxiety Research, in Horwitz, E.K., & Young, D. J. (eds.) Language Anxiety: From Theory and Research to Classroom Implications. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, pp. 15-24.

Swain, M. (1998). Focus on form through conscious reflection. In Catherine Doughty and Jessica Williams, eds. Focus on form in classroom second language acquisition, 64–82. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Swain, M. (2005). The output hypothesis: theory and research. In Eli Heinkel, ed. Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning, 471–483. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Yung, H. Y., & McCroskey, J. C. (2004). Communication apprehension in a first language and self-perceived competence as predictors of communication apprehension in a second language: A study of speakers of English as a second language. Communication Quarterly, 52, 170-181.

Please check the How to be a Teacher Trainer course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the English Language course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

|