Rachel Flees Religious Persecution: Teaching an Animated Video

Bill Templer, Bulgaria

Bill Templer is a Chicago-born educator with research interests in English as a lingua franca, critical pedagogy, minority studies and social justice issues in the EFL classroom. He has taught at universities in the U.S., Ireland, Germany, Iran, Israel, Bulgaria, Nepal, Thailand, Laos and Malaysia. Bill is active on the IATEFL Global Issues SIG Committee, the Editorial Board of theJournal for Critical Education Policy Studies, and withinBETAin Bulgaria. He is assistant editor at clelejournal.org and is also a widely published translator from German, particularly in the field of Jewish history and culture. Bill is based as an independent researcher in eastern Bulgaria. E-mail: templerbill@gmail.com

“No one leaves home unless home is the mouth of a shark”

--Warsan Shire (2015)

Menu

Introduction

Focusing on migration

Rachel’s Journey

Working with the video

German versions

Honing student social empathy

Wasan Shire’s poem “Home”

Conclusion

References

This article suggests a focus on the ‘migration crisis’ and ideas for a developing a lesson plan of your own centered on a brief animated video, “Rachel’s Journey from a Country in Eurasia,” the real-life story of a young teenage girl from a country in Central Asia, who at the age of 13 flees extreme religious persecution of her Christian family and becomes a refugee in the United Kingdom, for a time literally imprisoned in a British detention centre. It is also available as a picturebook (Glynne & Mosaic Films, 2014a) in simple English, accessible to advanced beginners, a touching and topical true tale with images moving and still. The article seeks to encourage ‘multiliteracies pedagogy’ approaches geared to real-world issues (Karastathi, 2016).

Bringing the world into the content we teach seems reasonable, necessary, imperative especially in these chaotic times. Exploring with students questions that are local, issues that are global, and that concern as citizens of a world in turmoil. We are all educators of the person, not just of the English language and communicative skills. As Paulo Freire stressed: “Conflicts are the midwife of consciousness” (Horton & Freire, 1990, 180). Social justice is a focus students often respond to, they know deep down that fairness is right and discrimination is wrong, persecution is wrong. They realize power games are being played all around them: “emancipatory literacy involves revealing the ways dominant power operates,” everywhere (Kincheloe, 2008, 104). To bring relevant issues into the EFL classroom is not illusory. It is basic, doable. It requires creating space in a crowded syllabus to breathe, reflect, question – not always easy. Linda Ruas (2017a):

We have to include some content to contextualise the languagewe teach and often find that published materials present a consumerist Eurocentric view of the world, which we might not want to perpetuate. […]but if we always avoid all these more controversial topics, our lessons could be bland, decontextualised and meaningless.How can we teach critical thinking if we don’t bring topics into class that learners can be critical about? […] We can take our teaching to a whole new level by raising awareness about these issues as well as teaching English. […] It’s impossible to ignore the real world of refugees, polarised opinions and increasing inequality.

Rachel’s narrative is about that “real world of refugees.” Persecuted and excluded from school in her native country, she flees to a new world of learning in the UK. The acclaimed American journalist and analyst Chris Hedges begins his talk about how he became a critical and questioning journalist (2015, min. 0:13-38), noting: “As Immanuel Kant said: ‘If justice perishes, human life on earth has lost its meaning.’ And any system of education that does not place social justice at its heart is not education. It is indoctrination.” This article is framed in that spirit.

One burning current topic we all have opinions about and awareness of is migration. Unavoidably so. Its often harrowing images and stories permeate the evening news. As McVeigh and Townsend (2016) write: “Itis now the greatest movement of the uprooted that the world has ever known.Some 65 million people have been displaced from their homes, 21.3 million of them refugees for whom flight is virtually compulsory – involuntary victims of politics, war or natural catastrophe.” Here in Bulgaria, for example, this involves many migrants coming through the country from Turkey and West Asia, some staying, most moving on, even fleeing the country. Many entering Bulgaria illegally. And they are confronting much hostility locally. Students are aware of this from the news, perhaps even from their own experience, including meeting children from a migrant family. But migration has another important face in Bulgaria: many younger Bulgarians dream of migrating westward to build a new life. In some cities, nearly 20% of the population has migrated abroad since 1990. Many students have relatives working outside the country longer-term if not settled there, in Western Europe, the US and elsewhere. There is a prolonged two-decade-plus economic and severe demographic crisis in BG. Ever more Bulgarian high school graduates are seeking to study abroad, a veritable youth brain drain:

A recent poll conducted on behalf ofBulgaria'seducationministry found that 52% of this spring's graduating high-school class applied for university abroad. One in six members of last year's graduating high-school class went on to foreign universities. The majority of these students will likely continue their careers outside Bulgaria. That creates enormous pressure on the domestic labor market, which is rapidly aging (Dyankov, 2013).

So for mounting numbers of Bulgarian students, becoming a migrant or immigrant themselves is a genuine option on their own very personal, local horizon. This is also true for young people in many countries these days, and most of them are studying English as part of their survival kit in uncertain times and fraught spaces. On the “age of migration,” see Castles & de Haas (2013).

This article develops ideas for creating your own lesson plan centered on a brief animated video, the real-life story of a young teenage girl, Rachel Nasib, from a country (unnamed) in Central Asia, who flees extreme religious persecution as a Christian. She narrates her own story in the short 5-minute video from BBC Two done in June 2012, then aged 17. Her story “documents the hostility and rejection that the family suffer at the hands of their community, as well as the courage and resilience they show in the face of immigration authorities, detention centres, deportation, and, finally, in overcoming their problems and settling in their new country” (Glynne & Mosaic Films 2014a, back cover).

This is one in a series of five animated stories, “Seeking Refuge,” of young refugees to the UK, “real-life stories about young people fleeing their homelands for various reasons to live in the UK, told by the children themselves.” As BBC says:

These films combine engaging testimony with rich animation and give a unique insight into the lives of young people who have sought asylum in the UK. Each of the films powerfully communicates the collective struggles and hopes of these young people and the issues they face adjusting to life in the UK. The series explores themes including immigration, persecution, separation and alienation and aims to help educate students at Key Stage 2 and 3. However young people and adults of all ages can enjoy these films.

The series won a prestigious BAFTA award in 2012. The social justice theme is persecution, in this case because of religion, as a Christian in a predominantly Muslim country. But it is also about discrimination and hardship that refugees face in the UK, the troubles that migrants seeking ‘asylum’ elsewhere encounter. We all see the horrible plight of families, children, mothers and fathers, in images and reports of refugees online and TV from the conflict in Syria. So this focus of migration and its problems is very topical, current. It raises questions about ethics, fairness, and what personal nightmare adults and children, normal people, go through who become migrants on a journey, as Rachel says: “it was a kind of journey that we wouldn’t know where it would lead to” (min. 1:39). So students can learn something about detention centres, for example, and the terrible insecurity of the fear of ‘deportation.’ In the United States, millions of migrants, most from Latin America, live in mounting fear today of deportation because they are “undocumented” immigrants. Undocumented students often do not like to discuss their situation, learning English as ELLs; see also Delaney 2016). Rachel’s animated story is also about ‘bouncebackability’ in the face of hardship, and enduring hope. What we all call in the states ‘true grit showing your toughness in dealing with any problem, your inner strength and persistence, existential resolve. The BC report Language for Resilience. The Role of Language in Enhancing the Resilience of Syrian Refugees and Host Communities (2017) is very relevant.

Students can also watch the animated video “Ali’s Story” from the same series about 10-year-old Muslim refugee Ali who, with his grandmother, flees Afghanistan to avoid the conflict caused by war which Kieran Donaghy has made into a superb lesson plan on his site Film English. The story “documents the feelings of alienation, separation and suffering that war can place on immigrant children and their families, and the thread of hope that can help them overcome their ordeal” (Glynne & Mosaic Films 2014b, back cover). Ali describes all the problems and confusion he endured at school in the UK since he didn’t know the language, just the word “yes.” But he soon makes good friends. Many of the excellent questions and lesson steps Kieran suggests could also be applied in working in class with the video about Rachel.

The clips of the three other stories in “Seeking Refuge” can also be watched and discussed by students, each is different: Navid from Iran, Juliane from Zimbabwe, Hamid from Eritrea.

Importantly, all these real-life stories also have a picturebook available, which teachers can acquire at relatively low-cost. So they could supplement viewing of the animated video with work on images & text of the picturebook (Glynne & Mosaic Films, 2014a) on Rachel’s journey.

As yet there are no story app digital picturebook versions of Rachel’s story (or Ali’s), perhaps there will be soon. On story apps, an extraordinary new narrative technology, see Koss (2013); Al-Yaqout & Nikolajva (2015); Brunsmeier & Kolb (2017), a digital tale-telling art. Apps contain interactive animations, puzzles, options for reader participation and co-creation. They integrate hotspots, options for changing settings, characters, tasks the reader needs to accomplish before the story continues, useful vocabulary support and oral narrative for pronunciation.

Teachers are encouraged to acquire Kieran’s book (Donaghy, 2015) and also to explore his site Film English for other very useful lesson plans, many oriented to global issues in the broad sense. Richard Leigh interviews Kieran here, and here regarding his new book Film in Action. Kieran talks here Glasgow IATEFL 2017, about his site on the occasion of winning a MEDEA award 2013. Donaghy (2016) is a recent interview on his work. He also has cofounded the Visual Arts Circle, also involved in the GISIG IATEFL Brighton 2016 Pre-Conference Event. More generally, BBC Two has a Learning Zone Short Films Primary and Secondary.

Rather than lay out a set lesson plan, I will suggest how to work with the film, supplemented by the picturebook if available, questions to explore, issues. Also relating them to learners’ real lives. Teachers can create their own lesson plans in as much detail as desired, perhaps likewise with input from their students. They can also explore techniques in critical “Deep Viewing” (Pailliotet, 1998) and a new book on image literacy in ELT edited by Donaghy and Xerri.

(a) First watch the video several times yourself. This is accessible online at the SWRMediathek in Switzerland under PlanetSchule (no longer at BBC), but be patient, it can take a few seconds to kick in. BBC Two informed me they cannot keep the original series online there.

(b) Introduce the film by first touching on its broader frame. Just as Kieran Donagh states in his Film English lesson plan for “Ali’s Story,” tell your class: “Students practise vocabulary related to refugees, speak about refugees, watch a short film, empathise with refugee children and write an account of a refugee child fleeing their country.” You can ask them what a ‘refugee,’ is, how that differs from a ‘migrant,’ what is ‘migration,’ what is ‘emigration,’ ‘immigration.’ What are the problems, the benefits that migrants and refugees bring to a country they go? What are the problems, the plusses that migrants cause for the home countries they leave? For example, in Bulgaria we see a serious shortage of many professionals, not just doctors, engineers, information science specialists, construction work specialists. And many of the better students going abroad to study and perhaps stay. Among the plusses are the cash transfers that migrants abroad send back to Bulgaria, more than one billion leva equivalent in 2016, a key income source for many families, especially in smaller towns with high unemployment and numerous villages.

(c) You can also ask students what ‘discrimination’ is, what ‘persecution’ especially religious, racial or political and students can discuss in groups. Is there religious discrimination in their own country, even learners’ direct experience, as here in Bulgaria 2017? A topic relevant in many countries these days is Islamophobia. Here an “Islamophobia is racism” syllabus with links and commentary, extremely useful for teachers. Ask learners: what religion was persecuted in Christian countries for centuries, culminating in the Holocaust? In fact, many Jews sought refuge 500 years ago in the Ottoman Empire, including Ottoman Bulgaria and Greece, Palestine. Many Bulgarians are unaware that Yosef Karo (1488-1575), one of Judaism’s most famous rabbis and a child refugee from Spain’s Inquisition, lived 1523-1536 in Nikopolis in Ottoman Bulgaria (cf. Keren, 2016), and later as refugee migrated to Ottoman Safed (צפת) in Galilee, buried there. Safed was a town I was living and working in when I decided to relocate in 1991 to Veliko Turnovo, 90 km SE of Nikopol. Rabbi Karo’s memory was recently celebrated in a Nikopol garden bearing his name.

(d) A very and controversial question is what rights and obligations a refugee should have, for example, in Bulgaria, a current heated topic and issue. How do their relatives, their parents, their neighbors feel about refugees, esp. from Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq and Pakistan, for example? Are there any migrants in their city or village, what do they know? How do students feel about the problems created locally for a Catholic priest aiding a Syrian refugee family to stay on in the town of Belene? People have protested in his support. An empathic perspective, mentioned by Donaghy for teaching “Ali’s Story,” is: “put yourself into the shoes of a migrant” coming to your own country. How can they be welcomed, integrated, made to feel more at home? Or the obverse: ask students also to imagine that they are a migrant in a strange, distant country, how might they feel, discussing in small groups. Maybe they have relatives who are abroad and tell about their experiences. Have any of your learners been abroad? How did they manage communicating? Did some use ‘English as a lingua franca,’ and how? They have stories.

Meanwhile, in the US, many are organizing to stop a veritable “war on immigrants,” including the program DACA, Deferred Action for Childhood. Students can explore and discuss this aspect of the migrant and refugee crisis, a burning issue in the US. Ever more teachers in the US are joining the grassroots movement of the People’s Congress of Resistance. Here the PCR Manifesto. It is concerned with problems of the “undocumented” in the US, and much more, “society for the many.” One counter-example is the progressive policy for refugees in Uganda.

(e) In working on basic vocabulary, K. Donaghy has a ‘refugee vocabulary’ sheet. You could put together something similar for “Rachel’s Story,” adding various key words from the text that could be highlighted before students watch the video.

(f) If you have the picturebook, you can show various spreads and ask students to describe what they see. One option is also to show the video without sound and ask students to describe several scenes, what they find striking. The film scenes are of course always ‘moving’ and brilliantly crafted. They show strong contrasts of many kinds, including men as huge giant ‘monsters.’

(g) Show the video. Then ask students to try to tell the story in their own words. They can tell the story to each other in pairs. Then perhaps collaborate as a whole class.

(h) Teachers can prepare a transcript of the entire text of Rachel’s story, readily audible. There are 632 words (tokens) of text in the picturebook version, the original video spoken text is longer and somewhat different. Perhaps a transcript can be given to students as they watch the film again. Or they can work together to produce a transcript, a useful group exercise. Rachel speaks very clearly, but some words will be more difficult to catch. Teachers can listen carefully and make a copy of the full text of the video, or acquire the 32-page picturebook. Most of the sentences are quite short, 11-15 words. The vocabulary is almost all in the first 1,000 basic words (K-1). There are only seven words in text a bit harder: appeal grant (K-2); hostility reject (K-3); distressing (K-4); detention dreadful (K-5), test lexis here. The Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level is ca. GL 6, Flesch Reading Ease 72. The film text is ca. F-K Grade Level 7.5, Reading Ease ca. 69.

There are clear differences in the text video/picturebook. For example, the animation narrative from min. 0:38-1:12 (88 words):

Because in the UK being a Christian isn’t a problem but in my country, which is a predominantly Muslim country, it wasn’t a favoured religion or tradition. But my mum kept on going secretly to church on Sundays, and when the police invaded the secret services that they were having, the whole atmosphere was kind of full of flames, it felt like everything was going to burst out. And my mum was treated very bad from the local citizens, and she felt like she wanted to escape somewhere. (88 words)

The picturebook has this text (70 words):

In many countries being a Christian isn’t a problem, but in my country it wasn’t an accepted religion or tradition. However, my mum kept on going secretly to church on Sundays. When the police invaded the secret church services, the situation became very difficult and dangerous. Our lives changed over night and my mum was treated very badly by the local people. She felt like she really wanted to escape.

Students can compare the two versions if the picturebook is available, a useful exercise. Teachers can transcribe the two texts in full and test for lexis (K-2,-3, etc.) and F-K grade level.

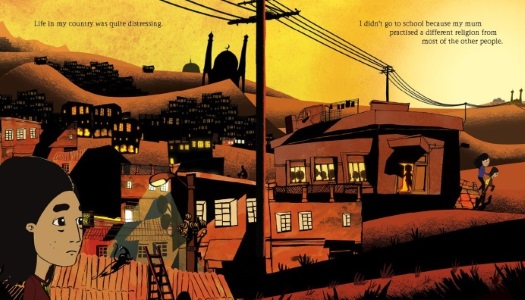

Below the first spread in the picturebook, students can describe details noticed. Is Rachel happy?

What is the pervasive color? Where is the school Rachel mentions? What dominates the skyline?

She says there: “Life in my country was quite distressing.” What does the word mean?

Figure 2. Rachel’s Story, spread 1

(i) A whole range of questions can be generated and explored. Rachel says at the beginning that she didn’t go to school because of her mother’s religion. Why? What violence is shown early on in the video? Does Rachel attend church with her mom? If not, why not? Rachel’s mentions her mother a lot but not her father, although we see him in the video and book. Can we explain that? How does the family escape their country and travel to the UK, a long overland journey? Do they find a ‘people smuggler’? What is that? Do you think they have a visa to enter? What kind of problems does Rachel encounter? First she is happy and has a normal life and friends, but then something happens. What is it? How does she describe being taken by the British authorities to a detention center? What are the images that come to mind? How are the men who arrest her portrayed visually? Students can try to empathize with her in detention: write a letter by Rachel to a friend, describing how she feels there and what has happened. Or write a short poem by Rachel. What happens after her family is released from detention? What terrible event then occurs? How does she describe this? How does the family manage back again in their country? What do they do? Does the video end, happily? What does Rachel say she wants to do with her life, a possible career? What do you think she is doing now in 2017? It has been 5 years since the video was made, she is now 22. Teachers can also ask students: what if you had Rachel’s story as a story app? What would you like it to do ‘interactively’? Some students may well have experience with story apps & drama, games. They could also act out an episode with Rachel working as a lawyer helping refugees, as she says: “I want to study law so that I can help people who have the same kinds of problems as my family and me.”

(j) Rachel doesn’t mention the actual name of her country. Eurasia is a term here for Central Asia, which includes Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan. They are all Muslim-majority countries that were republics within the Soviet Union before 1991. The situation of Christians in several countries there, especially Tajikistan, Turkmenistan is difficult. Perhaps Rachel is from there. Students can try to find out more about these countries. The situation of Christians is described in this article for Tajikistan, this for Turkmenistan. What do students learn from these clips? Can we trust what they say? In these countries, Muslims who convert to Christianity are especially harassed and persecuted. Perhaps Rachel’s mother is such a convert after 1991, we do not learn if Protestant, Catholic or perhaps Eastern Orthodox. Much of this persecution arose after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Why?

If you are teaching in Germany, Austria or Switzerland, or if you have students studying German as a second foreign language, you can also watch a version of Rachel’s story in German, “Rachel aus Zentralasien.” There is also a German version of Ali’s story, “Ali aus Afghanistan.” Students can make comparisons. All five BBC animated videos from Seeking Refuge in German (“Zuflucht gesucht”) are here.

Much of what students can learn from Rachel’s story has to do with developing a sense of empathy for her situation, how she felt and thought dealing with uprooting, detention, a new culture and country, deportation, persecution as a Christian at home. This is a video on “How do you spell discrimination?” on Roma and this is another one on diversity. How do students you teach view ‘others’ from an ethnic or religious minority? Can they try to imagine what they might feel in ‘their shoes’? That is empathy hands-on. Introduce social empathy to students watching and discussing this superb video from MindShift. Students can imagine getting into the mind of another―from fiction, the news, real life, or the point of view of an animal or even the imagined mind of a material object―and writing a short monologue or dialogue poem, a letter, a diary entry or a spoken poem or reflection. Roman Krznaric (2013, min. 0:50-1:05) defines empathy as “the art of stepping into the shoes of another person and looking at the world from their perspective … It’s about understanding where another person is really coming from.” Krznaric (2012) also focuses on social empathy, and the key dimension of “cognitive empathy,” (see his blog). A great further exercise attuned to getting students to see each other as persons and gain a real voice is Linda Christensen’s “Where I’m From: Inviting Students’ Lives into the Classroom” (2015), where learners are encouraged to write a short poem about their lives, about the worlds from which they come, local or distant. There are also sample student poems there. Students could write one about themselves, but also could write a ‘Where I’m From’ poem as if authored by Rachel, and then compare the different poems. It is also integral to emancipatory literacy.

This is a form of “interior monologuing,” as developed Christensen (2000, p. 131): “Students need opportunities to think deeply about other people—why they do what they do, why they think what they think. They also need chances to care about each other and the world. Interior monologues are a good place to start.” Interior monologuing asks: “How would you feel in that person’s place?” The monologue can take various forms: a poem by or about the person, a personal letter by her or him, a song text, a diary entry, other types of spoken or written text (Templer & Tonawanik, 2011).Students can likewise explore Roots of Empathy; on empathy, see also Templer (2017). Teachers can seek to familiarize themselves with PSHE (Personal, Social & Health Education) in the UK, which aims to develop pupils’ emotional intelligence, resilience, self-esteem, empathy; cf. also SEAL (Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning). This can help spark a ‘critical PSHE,’ partially through short BBC films like “Seeking Refuge,” and what we can call a ‘critical CLIL.’ It involves teaching centrally about cultural topics in ELT.

The Somali Kenya-born poet raised in London has written a poem that has become a rallying call for refugees and migrants, titled “Home” (Shire, 2015). As a supplementary literature assignment, students can read the poem and discuss it main points, relate it to what Rachel’s story teaches them, and perhaps write an essay on what the poem says to them personally about the migration crisis. As the poem ends: “no one leaves home until home is a sweaty voice in your ear saying/ leave,/ run away from me now, i don't know what i've become/ but I know that anywhere/is safer than here.” Here Warsan reads “Home.” The text is here, students can copy, read aloud. They can combine and compare this with her powerful 2011 poem “Conversations about Home (at the Deportation Centre).” Here she reads the poem. And explore Zakaria (2016), where Warsan also reads from her poetry, an excellent article. Wasan was named in 2013 London’s first Young Poet Laureate. Unlike Rachel, Wasan was an immigrant at the age of one.

This article has been written in the spirit of Hedges (2015) and the TDI in Toronto where Chris Hedges spoke, its view that “A more humane and accountable society requires educational institutions that are ethical, critical rigorous, and robust defenders of social justice.” That is a stance that many of us in the IATEFL Global Issues SIG share. Such an orientation is integral to bringing “creative, critical and compassionate thinking into ELT” (Pohl & Szesztay, 2015), everywhere. Ruas (2017b) is a new introduction to teaching GI, as is Ruas’ 3-book series Global Justice in Easier English. You can contribute to eLesson Inspirations, for example, an open GISIG online project (Templer, 2016). The GISIG motto CARE GLOBAL TEACH LOCAL is especially relevant these darkling days fraught with mounting crises, in a world system in ever deepening turmoil. It is also a perspective developed in Ellis (2013; 2015) and Lütge (2015). Cost-free from BC is Maley & Peachey (2017). The GISIG IATEFL Brighton PCE 2018 is ‘Social Justice and ELT Through the Visual Arts.’ On “Deep Viewing,” see Pailliotet (1998).

For an introduction to critical pedagogy, the encompassing framework here, geared to developing students’ ‘literacy of power’ in an increasingly power-inscribed world, see Kincheloe (2008), McLaren (2016), Giroux (2015). Our teaching needs to sow seeds of critical thought and glocal social empathy in students as citizens here in Bulgaria, across Europe and far beyond. This is the “midwivery of consciousness” in Freire’s classic sense: “What the educator does in teaching is to make it possible for the students to become themselves” (Horton & Freire, 1990, 181). Hedges (2017) explores what is wrong with schools in the US and elsewhere with Nikhil Goyal (2016), an incisive critic of his own elite education. Hedges concludes (min. 27:55): “Schools have become an appendage of the market economy. It’s not about teaching how to think but what to think. […] Our schools do not intentionally enable students to question ruling structures and assumptions. Only to serve them.” Too much of what we do in TEFL classrooms remains bereft of social conscience and social consciousness. That needs to change. Listen also to Prof. Douglas Kellner (2013a; 2013b) speaking on hidden curricula, media culture, “media spectacle.” The basic task is clear: question more a stance in heart and mindscape that through her experience, Rachel has definitely learned to apply.

Yet a teacher need not fully share those more system-critical views to appreciate and use what is presented here. Focus is on a simply narrated moving real-life personal story that all teenagers and even tweens, younger kids, adults can appreciate, and its language is basic enough for most lower intermediate (and advanced elementary) learners to follow well. This is multiliteracies pedagogy (Karastathi, 2016; Kellner, 2004) in a nutshell for learners of any age and background, and deals with a planetary issue ever more perplexing and insoluble (Castles & de Haas, 2013).

Al-Yaqout, Ghada & Nikolajva, Maria. 2015. Re-conceptualising picturebook theory in the digital age, Barnelitterært Forskningstidsskrift 6(1), 26971. http://goo.gl/7hHRks

Brunsmeier, Sonja & Kolb, Annika. 2017. Picturebooks go digital – The potential of story apps for the primary EFL classroom. Clelejournal, 5(1). http://goo.gl/s2q8zi

Castles, Stephen, de Haas, H. 2013. The Age of Migration. 5th ed. NY: Palgrave. goo.gl/vpXs15

Christensen, Linda. 2015. Where I’m from. Inviting students’ lives into the classroom. In Linda

Christensen, L., & Watson, D. (Eds.), Rhythm and Resistance. Teaching Poetry for Social Justice. Milwaukee: Rethinking Schools, 2015. http://goo.gl/ECCe9V; here her article.

Delaney, Marie. 2016. Can learning languages help refugees cope? Voices, British Council, 21 July. http://goo.gl/NkpBFp

Donaghy, Kieran. 2015. Film in Action. Teaching Language Using Moving Images. Peaslake, Surrey: Delta.

Donaghy, Kieran. 2016. Interview with Kieran Donaghy. By Vicky Papageorgiou. ELTA Newsletter (Serbia) 10(4), July-August, 17-22. http://goo.gl/j5khO8

Dyankov, Simeon. 2013. Ex FinMin comments on Bulgaria’s ‘endless’ protests for WSJ. Wall Street Journal. Reprinted in Novinite, 29 July. http://goo.gl/d2pAAI

Ellis, Maureen. 2013. The Personal and Professional Development of the Critical Global Educator. Doctoral thesis, U of London, 2013. Online in full: http://goo.gl/9q35QV

Ellis, Maureen. 2015. The Critical Global Educator. Global Citizenship Education as Sustainable Development. London: Routledge. http://goo.gl/EtuoSw

Giroux, Henry A. 2015. Where is the Outrage? Critical Pedagogy in Dark Times. McMaster University, Hamilton/Ontario, 24 Sept. http://goo.gl/gxFHky

Glynne, Andy & Mosaic Films. 2014a. Rachel’s Story – A Journey from a Country in Eurasia. S. Maldonado (Illus.). London: Wayland. http://goo.gl/jEAMLO

Glynne, Andy & Mosaic Films. 2014b. Ali’s Story – A Journey from Afghanistan. S. Maldonado (Illus.). London: Wayland. http://goo.gl/STl5F3

Goyal. Nikhil. 2016. Schools on Trial: How Freedom and Creativity Can Fix Our Educational Malpractice. New York: Doubleday. http://goo.gl/j3UoiE

Hedges, Chris. 2015. Education and Activism. Rethink Resist Reclaim. Lecture, 3rd Annual Tommy Douglas Institute, George Brown College, Toronto, May 21. http://goo.gl/d8hcHE

Hedges, Chris. 2017. On Contact: The failing education system with Nikhil Goyal. RT America, 8 April. http://goo.gl/O1bah5

Horten, Myles & Freire, Paulo. 1990. We Make the Road by Walking: Conversations on Education and Social Change. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. http://goo.gl/eMjr0c

Karastathi, Sylvia. 2016. Visual literacy in the language curriculum. Visual Arts Circle, 4 December. http://goo.gl/8QXw2T

Kellner, Douglas. 2004. Technological Transformation, Multiple Literacies, and the Re-visioning of Education. E-Learning, 1(1). http://goo.gl/KxngVv

Kellner, Douglas. 2013a. The Hidden Curricula of Education. UCLA. http://goo.gl/xQDCb1

Kellner, Douglas. 2013b. Youth, Media Spectacle and New Media. MCSPI SI, McMaster U,

16 July. http://goo.gl/rZaKLC

Keren, Zvi. 2016. The Jewish Community of Nikopol from Heyday to Dcline. In idem, Studies of Jewish Life in Bulgaria: From the 16th to the 20th Century. Tel Aviv: Contento Now. http://goo.gl/TybgT1 See also ARCS Publications, Sofia.

Kincheloe, Joel L. 2008. Critical Pedagogy Primer. New York: Peter Lang. http://goo.gl/bB1g7B

Krznaric, Roman. 2012. The power of outrospection. Video RSA Animate. http://goo.gl/GXwv8F

Krznaric, Roman. 2013. How to start an empathy revolution. Video’d talk, TEDxAthens. http://goo.gl/6k34Fr

Koss, Melanie D. 2013. Digital children's book apps: bringing children's literature to life in new and exciting ways. Reading Today, 31(3), 26ff. http://goo.gl/zawKAt

Lütge, Christiane. (Ed.). 2015. Global Education. Perspectives for English Language Teaching. LIT Verlag: Münster. http://goo.gl/EhBh5x

Maley, Alan & Peachey, Nik. 2017. Integrating Global Issues in the Creative English Language Classroom. London: British Council. http://goo.gl/Fxuo8b

McLaren, Peter. 2016. Life in Schools. An Introduction to Critical Pedagogy in the Foundations of Education. 6th ed. New York: Routledge. http://goo.gl/Q3VCpS

McVeigh, Tracy & Townsend, Mark. 2016. Why won’t the world tackle the refugee crisis? The Observer, 17 Sept. http://goo.gl/em9z02

Pailliotet, Ann Watts. (1998). Deep Viewing: A Critical Look at Visual Texts. In Joel. L. Kincheloe & Shirley R. Steinberg (Eds.), Unauthorized Methods: Strategies for Critical Thinking (pp. 123-136). New York: Routledge. http://goo.gl/8pDxoB

Pohl, Uwe, & Szesztay, Margit. 2015. Bringing Creative, Critical and Compassionate Thinking into ELT. Humanising Language Teaching, 17(2), April. http://goo.gl/Uit60t

Ruas, Linda. 2017a. Bring the world into your class. ELgazette, April 2017. http://goo.gl/go9xsb

Ruas, Linda. 2017b. Why Global Issues? UK: Academic Study Kit. http://goo.gl/Y9RtuD

Shire, Wasan. 2015. Home. http://goo.gl/53KxOd Also contained in Rabbi Michael Lerner, Mourning the suffering of the refugees. Tikkun, 4 September 2015. http://goo.gl/hWE4Wr

Templer, Bill. 2016. Introducing a new online tool: eLesson Inspirations on Global Issues. Humanising Language Teaching 18(4), August. http://goo.gl/sM5IBG

Templer, Bill. 2017. Introducing a classic lesson plan for two texts on discrimination. BETA E-Newsletter 27, Jan.-Feb., 30-40. http://goo.gl/Sw9liU

Templer, Bill, & Tonawanik, Phuangphet. 2011. Honing critical social imagination through a curriculum of social empathy. Humanising Language Teaching 13(4), August. goo.gl/hBpg5n

Zakaria, Rafia. 2016. Warsan Shire: The Somali-British poet quoted by Beyoncé in Lemonade. The Guardian, 27 April. http://goo.gl/nVEjT3

Please check the Methodology and Language for Secondary course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Practical uses of Technology in the English Classroom cours at Pilgrims website.

Please check the English Language course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Creative Methodology for the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the EFL Materials Development course at Pilgrims website.

|