Promoting Autonomy and Motivation through Applying Constructively Aligned Curriculum

Hossein Rahmanpanah, Iran

Hossein Rahmanpanah is Assistant Professor of TEFL at Islamic Azad University-South Tehran Branch, Iran. His main areas of interests are self-determination theory, SLA theories and concepts, materials development, and curriculum design. E-mail: Hossein_2003@hotmail.com

Menu

Introduction

Review of related literature

Methodology

Results

Discussion

References

According to Biggs (2003), constructive curriculum alignment is a design for teaching which clarifies what learning outcomes learners will achieve at the end of the instruction. In other words, constructive curriculum alignment is on this tenet that all assessment tasks, learning experiences, contents and methods used during the instruction must be linked or aligned to achieve the desired outcomes. That is why, it is easier for teachers to work from desired outcomes first, and then organize their content and teaching and learning activities based on their outcomes. As Biggs (1995) points out, “constructive” refers to this concept that learners construct meaning through relevant learning activities and “alignment” refers to the condition that teaching method used during the instruction, and assessment tasks are aligned to the expected learning outcomes. Therefore, constructive curriculum alignment helps learners understand what they are supposed to learn at the end of the instruction and this, in fact, highlights learners’ responsibilities in the learning process. Learning outcomes are defined as any type of behavior that learners can perform after the completion of the instruction (Biggs & Tang, 2007; McMahon & Thakore, 2006). Hence, teachers can determine learning goals and objectives once the intended learning outcomes are made. Undoubtedly, clarifying the expected goals provides alignment between the objectives required by the teacher and inputs and outcomes expected by the learners (McKone, 1999). However, aligning the teaching to construct the intended learning outcomes and its impact on developing learners’ autonomy and motivation has received little attention in EFL context. Hence, to bridge this gap, this study aims to explore the effect of constructively aligned outcome-based intervention program on fostering EFL learners’ autonomy and motivation within self-determination theory paradigm.

Constructive Curriculum Alignment

Many teachers begin with textbooks, forward lessons, and activities rather than taking desired results into consideration. In other words, many teachers focus on the teaching not the learning (Mcmahon & Thakore, 2006). Furthermore, teaching forms a complex system including teachers, learners, the teaching context, learners’ learning activities, and the outcomes. Hence, any attempt should be made to address the system as a whole, rather than taking only one component such as curriculum or teaching method into consideration (Biggs, 1999). Therefore, As Biggs and Tang (2011a) point out, in a coherently designed course, assessment tasks should mirror what the teachers intended the learners to learn and this coherence among assessment, teaching strategies, and intended learning outcomes in an educational setting is called constructive curriculum alignment. Constructive curriculum alignment is based on the two principles of constructivism in learning and alignment in the design of teaching and instruction. It is constructive because it is on the basis of constructivist theory in which holds that learners use their own activity to construct their knowledge or other outcomes. Furthermore, alignment refers to this fact that intended course outcomes are present in the learning activity and in the assessment tasks. To reformulate, the basic idea underlying constructive curriculum alignment is that the curriculum is designed in a way that the learning activities and assessment tasks are aligned to support learners to achieve the desired goals. Moreover, according to Biggs and Tang (2011b), to have a perfectly aligned curriculum, the teachers must apply alignment among the following three key elements of the curriculum:

- The intended learning outcomes;

- What the learners do to learn (teaching and learning activities);

- How the learners are assessed;

Figure 1 A Model of Constructive Curriculum Alignment (Biggs and Tang, 2011b)

As Figure 1 illustrates, under the tenets of constructive curriculum alignment, the teacher must formulate the outcomes of the instruction first, learning and teaching activities second, and assessment criteria the third. In constructive curriculum alignment, the teacher starts with the outcomes he tends the learners to learn and align teaching method and assessment procedure to those outcomes. To reformulate, teachers must clarify what the learners are supposed to learn at the end of the instruction. Biggs (1995) identifies the four following levels of understanding, with some illustrative verbs for each level:

- Minimal understanding is sufficient to deal with basic facts. Some illustrate verbs: memorize, identify, recognize;

- Descriptive understating deals with knowing about several topics. Some illustrative verbs: classify, describe, list;

- Integrative understanding deals with relating facts together. Some verbs: apply to known contexts, integrate, analyze, explain;

- Extended understating is going beyond what has been taught as it helps learners deal creatively with new situations. Some illustrative verb: hypothesize, reflect, generate;

As Biggs (2003) suggests, the first step in designing the curriculum objectives is to make clear what levels of understating the learners should be and then the teacher should determine the verbs that become the markers throughout the teaching and learning. Under the tenets of curriculum alignment, teachers are not the only responsible agents for setting up teaching and learning activities as learners are encouraged to construct their own learning. Biggs and Tang (2007) posit that teaching and learning activities fall under the following three headings:

- Teacher-controlled activities indicate teachers’ controlling effect on instruction. Lectures, tutorials, advance organizer, laboratories, discussion groups, brainstorming, and seminar are viewed as teacher controlled activities.

- Peer-controlled activities are the types of activities which vary from group work (Johnson & Johnson, 1990) to peer teaching and spontaneous collaboration among learners outside the classroom (Biggs & Tang, 2007).

- Self-controlled activities refer to specific strategies such as summarizing and note-taking that help the learners extract the meaning from the text (Hidi & Anderson, 1986; Kirby & Pedwell, 1991).

Learners’ intended learning outcomes are statements that explain learning outcomes that learners should demonstrate after the completion of the course (Biggs & Tang, 2007). Hence, statements of intended learning outcomes should clearly articulate the intended knowledge, skills, abilities, and competencies that should be covered during the course.

Autonomy and motivation within Self-determination Theory

Deci and Ryan’s (1985) self-determination theory (SDT) is an organismic-dialectic metatheory that explains the ongoing challenges faced by humans in terms of assimilating and adapting to social environments. Deci and Ryan’s self-determination theory assumes that learners are active organisms who are oriented toward developing and refining their capabilities by interacting with the physical and social environment, seeking out opportunities for choice, interpersonal connection, and integrating their ongoing experiences. However, at the same time, they might be vulnerable to control and passivity and may come to rely primarily on external influences for direction when conditions are not supportive of their innate tendencies toward growth (Niemiec, Ryan, & Brown, 2008). According to Deci and Ryan’s (2000), autonomy refers to being the perceived origin or source of one’s own behavior (Ryan & Deci, 2002). When autonomous, learners attribute their actions to an internal perceived locus of causality and experience a sense of choice over their actions (Reeve, Ryan, Deci, & Jang, 2008). Learners’ autonomy can be supported by teachers’ minimizing the salience of evaluative pressure and any sense of coercion in the classroom, as well as by maximizing learners’ perceptions of having a voice and choice in those academic activities in which they are engaged (Deci & Ryan, 2002). However, Deci and Ryan’s self-determination theory distinguishes between different types of motivation.

Figure 2 Types of Motivation within Self-Determination Theory Ryan & Deci (2000)

As Figure 2 shows, amotivation represents the state of lacking an intention to act.

Extrinsic motivations can be classified into external, introjected, identified, and integrated regulations. With external regulation, an individual engages in an activity to obtain external rewards or to avoid punishments. Also, learners guided by introjected regulation engage in the activity because of internal pressure, feelings of guilt or to attain ego enhancement. A more autonomous form of extrinsic motivation is regulation through identification. Identified regulation reflects participation in an activity because one holds certain outcomes of the behavior to be personally significant. Integrated forms of extrinsic motivation is observed when the activity with which a person identifies is more consistent with the individual’s values, needs, interests, and emotional regulations (Ryan & Deci, 2000). An educational course can be consistent when it is designed in a way that learning activities and assessment tasks are aligned with the learning outcomes. Constructively aligned curriculum enhances learner’ autonomy and motivation as it optimizes the likelihood that the learner is engaged in doing appropriate learning activities, being involved in a consistent system. In this regard, the researcher postulated that EFL learners’ autonomy and motivation will be fostered through implementing the principles of constructively aligned curriculum. To this aim, the following research questions are formulated:

- Does Biggs’ (2003) suggested framework of constructively aligned curriculum have

significant effect on enhancing autonomy among EFL learners?

- Does applying the principles of constructively aligned curriculum have significant impact

on developing EFL learners’ motivation within self-determinaton theory paradigm?

Participants

The researcher collected and analyzed the data from a sample group (N=40) of both male and female EFL learners, ranging in age from 22 to 34 years. The participants’ homogeneity was ensured through administered Oxford Placement Test (Allan, 1992). The subjects participating

in this study enrolled in a three-month TOEFL iBT academic essay writing preparation course. The whole instructional intervention program lasted for 18 sessions, each including 90 minutes.

Instruments

In this study, Deci and Ryan’s (2000) Academic Learning Self-Regulation Questionnaire was used to measure autonomy and controlled subscales among the participants. Academic Learning Self-Regulation Questionnaire measures autonomous and controlled regulations of the learners learn in particular settings such as college or university. This is a 7-point (1=Not at all true to 7=very true) Likert scaling questionnaire, including 12 items. This questionnaire was formed with the two subscales of controlled and autonomous regulations. According to Deci and Ryan, the reliabilities for controlled and autonomous subscales are approximately 0.76 and 0.80, respectively. Moreover, the Behavioral Regulation Questionnaire (Markland & Tobin, 2004) was used to measure the participants’ motivational regulations within SDT. This

is 5-point Likert scaling questionnaire (1= Not true for me to 5= Very true for me), including 19 items. The Behavioral Regulation Questionnaire contains five subscales that measure amotivation, external, introjected, identified, and intrinsic motivational regulations of the

participants within self-determination theory framework. As Markland and Tobin report, the reliabilities for the subscales of amotivation, external, introjected, identified, and intrinsic are 0.89, 0.89, 0.90, 0.91 and 0.91, respectively.

Data collection procedure

To explore the impact of constructively aligned outcome-based instructional program on fostering EFL learners’ autonomy and motivation, the researcher provided the participants with an instructional intervention, including 18 sessions. The participants were supposed to enhance their skill in TOEFL iBT academic essay writing. During the instructional intervention, the researcher applied the principles of constructive curriculum alignment (Biggs, 2003) to collect the data. The key assumption in curriculum alignment is that teaching system, especially the teaching methods used and the assessment tasks are aligned to the learning activities assumed in the intended outcomes. Therefore, the researcher, in this study, aligned the curriculum and its intended learning outcomes to the teaching methods used, and the assessment criteria used for evaluating the learning. To make the participants’ performance observable and measurable, the researcher selected some action verbs, while defining the intended learning outcomes. Table 1 illustrates data collection procedure applied to the participants during the instruction. Moreover, all the participants were asked to complete the Academic Learning Self-Regulation Questionnaire (Deci & Ryan, 2000) and Behavioral Regulation Questionnaire (Markland & Tobin, 2004) two times at the beginning and after the completion of the instructional intervention.

Table 1 Data Collection Procedure

| Learning outcomes |

Remembering: The participants were asked to remember the concepts taught during the instruction.

Understanding: The participants were asked to explain the concepts covered in the course.

Applying: The participants were asked to use the concepts covered during the instruction in a new way.

Analyzing: The participants were examined to see if they can distinguish among the concepts taught in the course.

Evaluating: The participants were asked to justify their decisions about the concepts taught during the instruction.

Creating: The participants were asked to write essays on assigned topics. |

| Teacher Activity |

PLectures;

mapping;

Questioning;

organizer |

Concept;Advance |

| Learner Activity |

Peer teaching;

Spontaneous collaboration;

Metacognitive strategy use; |

Group working; |

| Assessment |

Objective assessment: Multiple choice questions;

Performance assessment: Presentation, projects, writing reflective journals, portfolio;

Rapid assessment: Concept mapping, writing short essays, short analytical comments about the course, evaluating holistic understating; |

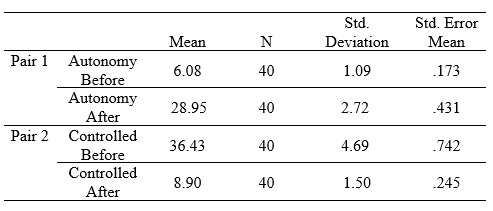

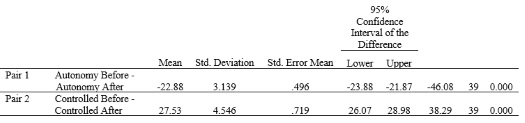

To explore the impact of constructively aligned curriculum on developing learner autonomy among the participants, the researcher computed paired t-test analysis between the data collected from two times of administering Academic Self-regulation Questionnaire. Table 2 reports the descriptive statistics for autonomy and controlled subscales.

Table 2 Descriptive Statistics of Autonomy and Controlled Subscales

As Table 2 illustrates, the mean for autonomy subscale increased from 6.08 (SD= 1.09) to 28.95 (SD=2.72). Nevertheless, the mean for controlled subscale declined from 36.43 (SD=4.69) to 8.90 (SD=1.50). However, to determine the significance of differences between the autonomy

and controlled mean scores from Time 1 to Time 2, the researcher computed paired t-test analysis between the collected data. Table 3 reports the results of paired t-test data analysis between autonomy subscales and the data collected from the controlled subscales.

Table 3 Paired t-test Analysis of Autonomy and Controlled Subscales

As Table 3 illustrates, there is a statistically significant mean score gain in participants’ autonomy level from the pre-scores to post-scores: t(39)= -46.08, p<.05. As it was hypothesized, negotiated-based intervention program fostered learner autonomy among the participants. In other words, when learners engage in behavior that they understand as self-initiated by choice and largely sustained by enjoyment in the activity, they are said to be autonomously motivated.

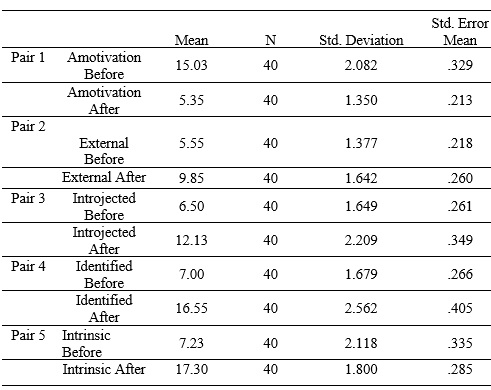

Table 4 Descriptive Statistics for Behavioral Regulation Questionnaire

As Table 4 displays, the means of identified and intrinsic subscales were 7.00 (SD=1.67) and 7.23 (SD=2.11) prior to SDT-focused intervention program, while it increased to16.55 (SD=2.56) and 17.30 (SD=1.80) after the completion of the instruction. However, the external and introjected subscales also increased after the completion of the instruction but the change was scarce for introjected subscale. The means of external and introjected regulations were 5.55 (SD=1.37) and 6.50 (SD=1.64) at Time 1 or prior to SDT-focused intervention program, while they increased to 12.13 (SD=2.20) and 16.55 (SD=2.56) after the completion of the instruction or at Time 2. More specifically, the results indicated that an autonomy-supportive teaching style within self-determination theory enhanced self-determined or autonomous forms of regulation (intrinsic and identified). However, the results indicated that the mean for the amotivation subscale declined after the completion of SDT-focused intervention program. As it is illustrated in Table 4, amotivation had the mean of 15.03 (SD=2.08) at Time 1, while it had a lower mean of 5.35 (SD=1.35) after the completion of SDT-focused intervention program. Therefore, the results were in harmony with arguments put forth by Deci and Ryan (2002). Moreover, to determine whether there was any difference between the mean scores, the researcher computed paired t-test data analysis and the results indicated that there is a statistically significant means score gain for intrinsic subscale from the pre-scores to post-scores: t(39)=-23.336, p<.05. Moreover, there is a statistically significant mean score gain in identified regulation or more autonomous form of self-determination theory: t(39)=-16.264, p<.05.

The results indicated that a constructively aligned curriculum enhances learner’ autonomy and

motivation as it optimizes the likelihood that the learner is engaged in doing appropriate learning

activities, being involved in a consistent system. Conversely, in an unaligned learning system,

where assessment is not aligned to the intended learning outcomes, or where the teaching

methods do not motivate appropriate learning activities, learners show great tendency to be

disengaged in doing learning activities, resulting in superficial learning (Biggs, 1999). The

findings indicated that any course planning or curriculum should be defined in terms of

outcomes, teaching or learning activities, and assessment tasks. Taking learners’ interests into

consideration with respect to the selection of content of the course, purposes, format of the tasks

or activities and even evaluation might create an exclusive consistency in curriculum design,

leading to higher learner motivation and perceived autonomy toward the learning climate. One of

the most important ways of relating to the learner or satisfying his needs is attunement (Reeve,

2006) or sensitivity. According to Reeve (2009), attunement occurs when the teacher feels

learners’ state of being and adjusts his instruction accordingly. When the teacher is attuned to his

learners, he knows what learners are thinking and feeling, and how involved they are during the

learning process. As Reeve points out, attuned teachers know what their learners want and need;

that is to say, they always align their teaching to construct the intended learning outcomes.

Therefore, this sensitivity allows the teacher to be responsive to learners’ words, needs,

preferences, and emotions, leading to greater autonomous perceptions among learners. Although

the tenets of teachers’ attunement or sensitivity (Reeve, 2009; Reeve & Jang, 2006) do not

address the second language learning domain, it appears that what the teachers do within

constructively aligned curriculum is being attuned to the learners as the teacher aligns intended

learning outcomes with teaching and learning activities, and assessment criteria, makes efforts to

identify learners’ autonomous resources, relies on informational language, creates opportunities

for learners to be emotionally, cognitively, and even behaviorally engaged, and is responsive to

learners’ needs and motivation during the instruction.

There is no doubt that constructively aligned outcome-based teaching is more effective than unaligned instruction because there is maximum consistency during the system. Learners might not feel motivated in the learning process when assessment is not aligned to the intended learning outcomes or even teaching methods. Hence, the principles of curriculum alignment is a link between a constructivist learning and an aligned design for teaching that is designed to highly motivate learners into deep learning. This study provided evidence on the fact that teachers must be clear about what they want their students to learn and what their students should do to show they have learned at the appropriate level. Besides, this study suggests that language teachers should implement diverse approaches to enforce their learners to learn at an effective cognitive level, using more learner-centered teaching-learning activities and assessment tasks. Where assessment tasks are not aligned to desired learning outcomes, or where the teaching methods do not encourage appropriate learning outcomes, learners might engage in doing inappropriate learning activities, leading to amotivation. In a nutshell, constructive curriculum alignment, through linking the constructivist understanding of the nature of the learning and aligned design for teaching, not only motivate learners into deeper learning but also enhances their perceived autonomy toward the learning environment.

Biggs, J. (1993). From theory to practice: A cognitive systems approach. Higher Education Research and Development 12, 73-86.

Biggs, J. (1995). Assessing for learning: Some dimensions underlying new approaches to educational assessment. Alberta Journal of Educational Research 41, 1-18.

Biggs, J. (1996). Assessing learning quality: Reconciling institutional, staff and educational demands. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 21, 5-15.

Biggs, J. (1999). Teaching for quality learning at university: What the student does. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Biggs, J. (2003). Teaching for quality learning at university. Buckingham: The Open University Press.

Biggs, J. & Tang, C. (2007). Teaching for quality learning at university. Maidenhead: Open

University Press. McGraw Hill.

Biggs, J. & Tang, C. (2011a). Teaching for quality learning at university fourth edition: Open

University Press. McGraw Hill.

Biggs, J., Tang, C. (2011b). Train-the-trainers: implementing outcomes-based education in

Malaysia. Malaysian Journal of Learning and Instruction, 8, 1-20.

Campbell, J. P., & Campbell, R. J. (1988). Industrial organizational psychology and productivity:

The goodness of fit. In J. P. Campbell & R. J. Campbell (Eds.), Productivity in organizations

(pp. 82-93). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Connell, J.P. (1990). Context, self, and action: A motivational analysis of self-esteem processes

across the life-span. In D. Cicchetti (Ed.), the self in transition: From infancy to childhood

(pp. 61–97). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Connell, J. P., & Wellborn, J. G. (1991). Competence, autonomy, and relatedness: A

motivational analysis of self- esteem processes. In M. R. Gunnar & L. A. Sroufe (Eds.), Self

processes in development: Minnesota symposium on child psychology (pp. 167–216).

Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Corno, L., & Mandinach, E. B. (1983). The role of cognitive engagement in classroom learning and motivation. Educa-

tional Psychologist, 18(2), 88–108.

Crawford, B. A. (2000). Embracing t

Corno, L., & Mandinach, E. B. (1983). The role of cognitive engagement in classroom learning and motivation. Educa-

tional Psychologist, 18(2), 88–108.

Crawford, B. A. (2000). Embracing t

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human

behavior. New York: Plenum.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The what and why of goal pursuits: Human needs and the

self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 227-268.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2002). The paradox of achievement: The harder you push, the worse

it gets. In J. Aronson (Ed.), Improving academic achievement: Contributions of social

psychology (pp. 59-85). New York: Academic Press.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human

motivation, development, health. Canadian Psychology, 49(3), 182-185.

Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., & Guay, F. (2013). Self-determination theory and actualization of

human potential. In D. McInerney, H. Marsh, R. Craven, & F. Guay (Eds.), Theory driving

research: New wave perspectives on self-processes and human development (pp. 109-133).

Charlotte, NC: Information Age Press.

Greene, B. A., & Miller, R. B. (1996). Influences on course achievement: Goals, perceived

ability, and cognitive engagement. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 21, 181–192.

Hattie, J.A.C. (2009). Visible Learning: A Synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses on Achievement.

London: Routledge.

Hidi, S., & Anderson, V. (1986). Producing written summaries: Task demands, cognitive

operations and implications for instruction. Review of Educational Research, 56, 473- 493

Johnson, D.W. & Johnson, R.T. (1990). Learning together and alone: Cooperation, competition

and individualisation. Englewood Cliffs NJ: Prentice-Hall.

McKone, K. E. (1999). Analysis of student feedback improves instructor effectiveness. Journal

of Management Education, 23(4), 396-415.

McMahon T. & O’Riordan D. (2006). Introducing Constructive Alignment into a Curriculum:

Some preliminary results from a pilot study. The Journal of Higher Education and Lifelong

Learning, 14, 11-20.

McMahon, T. & Thakore, H. (2006). Achieving constructive alignment: putting outcomes first.

The Quality of Higher Education, 3, 10–19.

Niemiec, C. P., Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2010). Self-determination theory and the relation of

autonomy to self-regulatory processes and personality development. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.),

Handbook of personality and self-regulation (pp. 169-191) Malden, M.A.: Blackwell

Publishing.

Peterson, C., Maier, S. F. & Seligrnan, M. E. P. (1993). Learned helplessness: A theory for the

age of personal control. New York: Oxford.

Ramsden. P. (1992). Learning to teach in higher education. Routledge: London.

Ramsden, P. (1984). The context of leaning. In F. Marton, D. Hounsell, and N. Entwistle, N. (Eds), The experience of Learning. Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press.

Reeve, J. (2013). How students create motivationally supportive learning environments for themselves: The concept of agentic engagement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105, 579-595.

Reeve, J., Ryan, R. M., Deci, E. L., & Jang, H. (2008). Understanding and promoting autonomous self- regulation: A self-determination theory perspective. In D. H. Schunk & B. J. Zimmerman (Eds.), Motivation and self-regulated learning: Theory, research, and applications (pp. 223-244). New York: Lawrence Erlbaum

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 54-67.

Spady, W. (1994). Outcome-based education: Critical issues and answers. Arlington: American

Association of School Administration.

Williams, G.C., & Deci, E.L. (1996). Internalization of biopsychosocial values by medical

students: A test of self-determination theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

70, 767–779.

Young, M. R. (2005). The motivational effects of the classroom environment in facilitating self-

regulated learning. Journal of Higher Education, 27(1), 25-40.

Please check the How to be a Teacher Trainer course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the Teaching Advanced Students course at Pilgrims website.

|