Current Trends in Teacher Performance Evaluation in Portugal

Carlos Ceia, Portugal

Carlos Ceia is associate professor of Contemporary English Literature and Literary Theory at the Department of Modern Languages, Cultures and Literatures, Faculty of Human and Social Sciences, New University of Lisbon – Portugal, head of the Language Institute of the New University of Lisbon (ILNOVA) and researcher at the Centre for English, Translation and Anglo-Portuguese Studies.

E-mail: cceia@fcsh.unl.pt

Menu

Background

A profile of the current and future teacher of English Language in Portugal at Basic and Secondary Schools

What is the graduation profile of the future English Language teacher?

The need for teacher certification

Dimensions of teacher performance evaluation

Designing a system for the evaluation of teachers

Approach to establishing validity of assessments

Models of teacher performance evaluation in English

Conclusions and general prospect

References

In 1983, the publication of A Nation at Risk1 in the United States led to a number of reforms aimed at improving the quality of education. National standards were developed to define “accomplished teaching and formally recognize teachers who meet these standards by awarding them advanced-level certification, beyond the basics needed for initial licensure.”2 The social diagnosis at that time included statements as “We report to the American people that while we can take justifiable pride in what our schools and colleges have historically accomplished and contributed to the United States and the well-being of its people, the educational foundations of our society are presently being eroded by a rising tide of mediocrity that threatens our very future as a Nation and a people.” The educational risks were identified and included:

- International comparisons of student achievement, completed a decade ago, reveal that on 19 academic tests American students were never first or second and, in comparison with other industrialized nations, were last seven times.

- Some 23 million American adults are functionally illiterate by the simplest tests of everyday reading, writing, and comprehension.

- About 13 percent of all 17-year-olds in the United States can be considered functionally illiterate. Functional illiteracy among minority youth may run as high as 40 percent.

The Law Act 3/2008 (“Decreto Regulamentar n.º 3/2008”) created by the Portuguese Ministry of Education to introduce teacher performance evaluation in Portugal did not emerge as a result of a previous national reflection on the state of education in Portugal – many of those symptoms (“risks”) identified in 1983 in the USA are still present in Portugal in 2009 –, is not connected with professional certification, and does not follow national standards for teacher performance, but materialized as an attempt to promote accomplished teaching through rigid bureaucracy and incongruous regulations.

We have professionals in our Basic and Secondary schools teaching English as a Second/Foreign Language with completely different educational backgrounds, tough they all teach the same curriculum, have the same income, and are being currently evaluated with the same criteria. The recent history of teacher education in Portugal and the way different policies about teacher development have been applied at private and state universities and polytechnics does not lead us to a positive view about the current official procedures towards teacher performance evaluation.

In 1998, a national agency for the accreditation of programmes of initial teacher education was founded - National Institute for the Accreditation of Teacher Education / Instituto Nacional de Acreditação da Formação de Professores (INAFOP) [DL 290/98]. Before this agency could complete its mission, it became extinct by the Portuguese Government in 2002. In 1994, a Parliament Act introduced a system for the evaluation of higher education courses and institutions, and later the Portuguese Universities Foundation assumed that task. The new National Council for the Evaluation of Higher Education - Conselho Nacional de Avaliação do Ensino Superior (CNAVES) [DL 205/98] - concluded two external evaluations of all university courses in Portugal. In 2007, it was closed and a new national agency is created: the Accreditation and Evaluation Agency of Higher Education (Agência de Avaliação e Acreditação do Ensino Superior [DL 369/2007]). Until this moment, the new agency has not initiated any process of accreditation or evaluation of higher education courses. (It is intended to start in January 2010.)

As seen, we still do not have an effective general system of degree accreditation. Professional associations of some of the regulated professions have started and run their own accreditation systems, but this does not include teacher education. This gloomy scenario of deregulation of the whole system of Portuguese higher education means that our English Language teachers finished their courses and pre-service education and have applied to the same job with no distinction whatsoever of their higher education profile. This is the beginning of a sad story that will lead us to our current issue: who are the Portuguese English Language teachers submitting their professional performance to a national evaluation system?

From 1984 (DL 34/1984) until now (DL 43/2007), English Language teachers (and all others) of Portuguese Basic and Secondary Schools have been graduated in one of the following general possibilities (not teacher training models but legal frameworks):

- BA (=Licenciatura) plus pre-service teacher education (5 years)

- BA (=Licenciatura) plus pre-service teacher education (6 years)

- BA integrating pre-service teacher education (4 years)

- BA (=Licenciatura) integrating pre-service teacher education (5 years)

- BA (=Licenciatura) plus pre-service teacher education (= Master degree) (5 years)

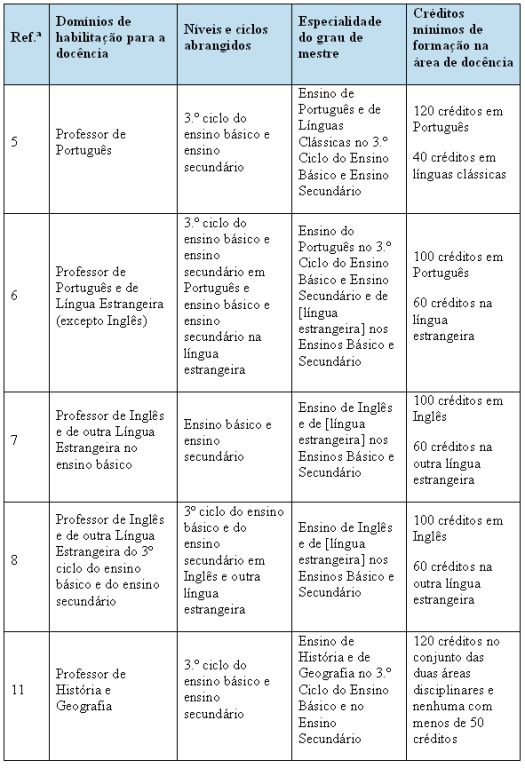

Only from 1998, has it been made compulsory for institutions to organize teacher education programmes for preschool and for the first cycle of basic education achieving a first degree (=Licenciatura). This was important for Teacher Education Colleges (Escolas Superiores de Educação - institutions of non-university higher education that developed out of former Normal Schools). If the initial teacher education varies from 4 to 6 years in the past two decades, the curricular profile of those courses are even more diverse (I have counted 64 different BA courses in Modern Languages available before the implementation of the Bologna process), and the professional conditions that a graduate could expect, once completed the pre-service education, from the legal framework were frustrating. In my opinion, the most problematic and iniquitous situation was always the fact that a graduate in Modern Languages - formerly designated Línguas e Literaturas Modernas, and currently Línguas, Literaturas e Culturas [Languages, Literatures and Cultures] - with a specialization in Portuguese and English (the most popular specialization) was not placed at the same career level as a graduate in English and German, due to an outdated and bizarre sheltering of those who graduated in the old course of Germanic Philology. In 2006, a new law (DL 27/2006) corrected this iniquity, here simplified3, and created a single group designated English. But a brand-new law (DL 43/2007) has changed, again, the curricular framework of the ELT training, and, from here, the old bizarre sheltering pictured in the specialization in Germanic Philology has been restored. The even more bizarre new curricular framework is as follows:

Ref.ª

Domínios de habilitação para a docência Níveis e ciclos abrangidos Especialidade do grau de mestre Créditos mínimos de formação na área de docência

5 Professor de Português 3.º ciclo do ensino básico e ensino secundário Ensino de Português e de Línguas Clássicas no 3.º Ciclo do Ensino Básico e Ensino Secundário 120 créditos em Português

40 créditos em línguas clássicas

6 Professor de Português e de Língua Estrangeira (excepto Inglês) 3.º ciclo do ensino básico e ensino secundário em Português e ensino básico e ensino secundário na língua estrangeira Ensino do Português no 3.º Ciclo do Ensino Básico e Ensino Secundário e de [língua estrangeira] nos Ensinos Básico e Secundário 100 créditos em Português

60 créditos na língua estrangeira

7 Professor de Inglês e de outra Língua Estrangeira no ensino básico Ensino básico e ensino secundário Ensino de Inglês e de [língua estrangeira] nos Ensinos Básico e Secundário 100 créditos em Inglês

60 créditos na outra língua estrangeira

8 Professor de Inglês e de outra Língua Estrangeira do 3º ciclo do ensino básico e do ensino secundário 3º ciclo do ensino básico e do ensino secundário em Inglês e outra língua estrangeira Ensino de Inglês e de [língua estrangeira] nos Ensinos Básico e Secundário 100 créditos em Inglês

60 créditos na outra língua estrangeira

11 Professor de História e Geografia 3.º ciclo do ensino básico e ensino secundário Ensino de História e de Geografia no 3.º Ciclo do Ensino Básico e no Ensino Secundário 120 créditos no conjunto das duas áreas disciplinares e nenhuma com menos de 50 créditos

The consequences for this Law Act are catastrophic:

- It is unfounded, from all viewpoints and scenarios, the establishment of a scientific domain called: “Teaching of Portuguese and Foreign Language, except English”. No one could think of a more bizarre exception. I have no knowledge of such in any other country in the civilized world.

- This Law contradicts another Law (DL 27/2006) that is currently regulating the teaching habilitation groups, where English is placed as a single discipline (Group 330, for “3º Ciclo” [3rd Cycle] and Secondary Education). No one knows, at this point, how both laws will coexist when the first teachers graduated with a master in teaching will finish their graduation and will seek for a post as English Language teachers.

- The BA in Portuguese and English Studies was eradicated from this Law and no one knows why. This thoughtless decision will oblige these graduates to follow an extra course in a second language (at least 60 ECTS) if they want to teach either Portuguese or English (no one can postgraduate in both languages with this Law and that is just another absurdity of this political Act).

- Those who hold a degree in English Studies at BA level (180 ECTS, as in any other BA bilingual course) will never be accepted as candidates to the master in teaching foreign languages. They are the graduates who hold more credits in English but they were mysteriously left out of postgraduate teaching courses.

- This Law ignores the Common European Framework of Reference for Language Learning and Teaching, < http://www.alte.org/can_do/ framework/index.php >), and does not agree with several decisions of the European Commission for teacher education in foreign languages. Just an example, one that is already at stake in our master programmes for teaching education: in European universities, to reach the level of the Cambridge ESOL Certificate of Proficiency in English (CPE), it is necessary to complete level C2 (approx. 1,000-1,200 hours or 8 years of study). In Portugal, from now onwards, it is possible to become an English Language teacher with C1 level, in some cases, or with level B2 in many others.

This will be the professional profile of our future teachers of English Language. How should we evaluate, now and in the future, English Language teachers with so different backgrounds? Will their performance be fairly evaluated when they have been educated so differently? Legally, this question is irrelevant since no one can be punished for having graduate with bad laws. One can fairly graduate with honours in a bad course under a bad law. This is not the point here. If we are still thinking and debating how to establish teacher performance evaluation methods and regulations, then is it the moment to rethink what can be done to correct ill-fated laws.4

The new national master courses – inevitably conceived under the regulations of the DL 43/2007 – for pre-service teacher education have very different curricular outlines. For instance, if you want to become a teacher for 1st Cycle, you will need 60 ECTS5 ; if you aim at 1st and 2nd Cycles, you will need 120 ECTS ; if you aim at 3rd cycle and secondary schools, you will have courses of 90 to 120 ECTS6. In any case, none of these master courses presupposes research work and/or a public defence of a dissertation. All that is required is a public defence of a final report of what has been done during the pre-service activities (“Prática de Ensino Supervisionada”). These curricular programmes have been planned to protect the strictly pedagogical contents of teacher education. As we will see, it is not possible to accept that the education of an English Language teacher neglects so evidently his/her technical instruction, in favour of a strong orientation towards pedagogical seminars, in spite of the fact that the current evaluation of teacher effectiveness and performance in Portugal seems to pay attention only to these achievements. This has been an historical miscalculation in the Portuguese educational system for the past thirty years.

A much different curricular framework has been adopted in foreign countries for pre-service and in-service teacher education and teacher performance evaluation. I will use the United States and the United Kingdom as comparative terms to Portuguese policies in this area. A major difference is the balance between pedagogical and technical knowledge during pre-service education. When defending research-based teacher education I am not claiming a cutback of pedagogical learning. I believe that both should exist either in pre-service or in in-service teacher education, but the focal point should be the former (specialized knowledge of the subject matter one teaches) and not the latter (the way one teaches). A few examples: the University of Maryland requires that “Candidates for the M. Ed. Program in Foreign Language Education must meet the following degree requirements:

- Completion of a minimum of 30 semester hours of the prescribed course work at the graduate level,

- Completion of one fully approved Seminar Paper written under the direction of a faculty member in the program, and

- A passing score on six (6) hours of a written comprehensive examination at the end of coursework. The examination covers all the major areas of study and is given twice a year, in early fall and early spring.”7

The University of Exeter, School of Education and Lifelong Learning, dictates similar rules for the assessment of the Master of Education (MEd), Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL):

Each of the taught modules is assessed by one or two written assignments.

You may choose to undertake a 10,000 word (30 credits) or 20,000 word (60 credits) dissertation depending on your academic and professional background8

The new master courses for pre-service teacher education in Portugal were not designed aiming to multidisciplinary contexts and do not, indeed, promote any kind of dialogue between foreign languages and other disciplines. English Language teachers in Portugal were not educated with pre-service programmes that would encourage multidisciplinary approaches to teaching a foreign language; therefore I believe that their performance will never be tested in that direction. Instead of stringent master courses for teacher education as those we have described in Table 1, we should prepare our future English Language teachers for all forms of interdisciplinary teaching, a principle that will foster a more democratic school needed in a multicultural society. I take the MA courses of the University of Warwick as good examples of pre-service teacher education in EL teaching:

- MA in English Language Teaching

- MA in English Language Teaching for Specific Purposes

- MA in English Language Teaching to Young Learners

- MA in English Language Studies and Methods

- MA in English Language Teaching and Multimedia

- MA in British Cultural Studies and English Language Teaching9

Under the DL 43/2007, we will never be able to educate an EL teacher as in the case of this last programme which introduces its objectives in terms that make sense to the Portuguese educational context: “This course aims to enable participants to enhance their understanding of social, cultural, educational and linguistic issues involved in the teaching of English in different national and professional contexts and to develop their professional skills, flexibility and research capability in ways which will benefit them in their future career in the field.”10 An English Language teacher has to have this imperative “understanding of social, cultural, educational and linguistic issues involved in the teaching of English in different national and professional contexts”, and it is expected that he/she will be evaluated when performing that understanding in real teaching situations. If we exclude this dimension from pre-service curricula or if it is just put in the shade of other pedagogical procedures, we are excluding a major competence of any future FL teacher. It would be even worse to think that that understanding will be excluded from later teacher performance evaluations.

I take these examples to show that, in these countries, it is a major standard in teacher education to require a profound knowledge of the most recent advances of the research in the subjects planned for teaching11. Hannele Niemi, from the University of Helsinki, member of a group of experts named by the European Commission, in the field of teacher education, who were to elaborate common European principles for teacher competences and qualifications, sums up what is needed:

The necessary prerequisite is that teacher education rests on a research-based foundation with three basic conditions:

- Teachers need knowledge of the most recent advances in research for the subjects they teach. In addition, they need to be familiar with the newest research on how something can be taught and learned. Interdisciplinary research on subject content knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge provides the grounds for developing teaching methods that can be adapted to suit different learners.

- Teacher education in itself should also be an object of study and research. This research should provide knowledge about the effectiveness and quality of teacher education implemented by various means and in different cultural contexts.

- The aim is that teachers can internalise a research-orientated attitude towards their work, which means that teachers take an analytical and open-minded approach to their work, draw conclusions based on their observations and experiences, develop teaching and learning environments in a systematic way12.

The research-based approach has been pigeonholed as one of the paradigms of teacher education as it can easily integrate theory and practice in real contexts taken from the students' work in school. Unfortunately, neither in pre-service nor in in-service teacher education in Portugal has been considered this paradigm from law acts to real practices.

The DL 43/2007 refers “educational research” only and, fallaciously, justifies itself as a Law Act that values, in particular, the dimension of subject matter competence and the validation of teacher education in research13. No one knows, in practical terms, what this means. No one has ever been tested on research-based work results in teacher education programmes. How something can be taught and learnt in teacher education in itself should also be an object of study, but only in rare moments of pre-service programmes this dimension is considered. In-service teachers are seldom familiar with the most recent research work in their subject matter produced by universities and research units. The official document (latest version published in late February 2009) of the Ministry of Education about teacher performance evaluation does not mention research in any case14. This means that the Government does not expect any teacher to integrate academic research-based knowledge with their own professional practice. Portuguese teachers will be evaluated on account of what they do in class, how they do it, and how students react to teaching performance. They will not be evaluated, for instance, on how they use technical literacy in authentic projects or effective teaching. Research-oriented attitudes and continuous learning minds help teachers to see their profession as a challenging career; a political agenda oriented to pedagogical and administrative evaluation will not help teachers neither in increasing their status in society and among other professions nor in the establishment of an inspiring career. A career structured this way will not attract the best candidates, at least those who like to think of teaching as a means to intellectual fulfilment, a paradigm that the current political situation seems to find an old utopia.

If a country wants to reform the whole educational system one would expect that that reform is accomplished because a conceptual or theoretical framework was designed prior to any effective implementation. Portuguese reform in education for the past decades lack that kind of organization since what is at stake is always the four years agenda of governments. We have a system of professional certification that relies entirely in under-graduation degrees and in pre-service teacher education. Foreign language teachers are not certified otherwise during their entire career. We lack a system of certification beyond these levels of education. In terms of internationalization, such a status is not recommendable for a foreign language teacher.

In the United Kingdom, teacher certification is carried out by UCLES (University of Cambridge Local Examinations Syndicate) and through the exams of Trinity International Examinations Board of Trinity College, in London. CELTA (Certificate in English Language Teaching to Adults) is an international certification recognized everywhere as a symbol of excellence for teaching English. The Trinity College offers a similar certification (CertTESOL: Certificate in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages. After a period of two years of professional experience, as a rule, the teacher decides if she/he wants to stay in the profession. If so, the teacher can proceed to a Master programme, for instance. The State may require an additional certificate – the Certificate in Further Education Teaching Stage 3 and/or the Certificate for ESOL Subject Specialists – if a more secure position is desired by the teacher. A Primary School teacher can obtain certification with the Post-Graduate Certificate in Education (PGCE).

In all these cases, we are talking of well-consolidated frameworks for teacher education, and therefore it should be easier to implement a system of teacher performance evaluation with international recognition. Unlike the Portuguese current system, the UK general framework of certification was not born as a means to correct decades of failures in teacher education and employment of teachers without further certification or long-life professional education. British certification of teachers was designed following the reforms of undergraduation degrees in universities and not against these reforms of even ignoring them, as it is the case of Portugal.

The new type of assessment that all future teachers, holding a master course in teacher education, will have to be submitted to, according to the new national regulations, is a weak agenda to national certification of teachers who want to sign State contracts. This is the wrong agenda because you should not test pre-service teachers who have just acquired a master degree in teaching in a sitting-test of two hours. This is bad certification and a flawed message to future teachers. Certification should be tied to effective teacher performance and not to testing recent acquired competences in a written paper or test.

When you live in a sustained educational system, no one fears certification of professional competences. The United States can be proud of this. They have founded the National Board for Professional Teaching Standards (NBPTS)15 , a national and independent agency which is nothing like the structure created by the Law Act 3/2008 (“Decreto Regulamentar n.º 3/2008”) created by the Portuguese Ministry of Education, a spurious idea for regulating the access to the profession.16

Any national certification should be regulated according to international models and influential diplomas. Current Portuguese certification for a teacher education job does not refer to international standards. For instance, it is possible for a Portuguese graduate at BA level to complete a master in teacher education for English Language in any foreign university, and after that acquiring CELTA certification (according to the University of Cambridge, over 10,000 people successfully complete a CELTA course each year). If such a candidate will ever want to teach English in a Portuguese Basic or Secondary school in the future, from now on, he/she will have to be extra-tested following the requirements of the Decreto Regulamentar nº 3/2008 and might fail, although he/she is already certified to teach English anywhere else in the world.

Portugal has now a system of certification for teaching that relies only in an exceptional test – still to be put in practice and regulated – but so powerful that it can determine if the graduate teacher will begin his/her career or not. If successful, the new Portuguese teacher will be tested in the years to come following the already announced teacher performance evaluation method. But none of these – professional certification and performance evaluation – was ever conceived under a conceptual framework for professional standards. In Portugal, the former INAFOP has tried to build such standards for teacher education17, but this entity was closed in 2002 and nothing else was done. To be certified as a future teacher and to be evaluated as an inservice teacher are two instances that should be connected.

In the United States, the NBPTS can proceed to teacher certification because we know, before hand, that national recognized standards have been fixed referring to competences for teaching a foreign language, for example. We do not have such referrals as the “World Languages Other than English/Early Adolescence through Young Adulthood”18. At this level, if a candidate wants to become a FL teacher, he/she will be tested not through classical written examination in educational topics, but through two fundamental competences:

- Candidates submit a portfolio comprised of three classroom-based entries, including two videos, to document the candidate's teaching practice. The fourth portfolio entry documents the candidate's work with students' families and the community as well as work within a professional community.

- Candidates must make an assessment center appointment where they will respond to six prompts focused on content knowledge. Candidates are allowed up to 30 minutes to respond to each prompt.

This model praises the academic background, follows the methods already used by the candidate during his/her graduation, believes in the practice of portfolio presentation, does not undervalue the linguistic competences of the candidate, and does not raise the suspicion that the institution where the candidate has graduated might not be reliable.

In Portugal, we do not have a description of teaching standards for English Language, which could help teacher performance evaluation both at pre-service and in-service education. My newly research group TEALS19 will try to build such standards in the near future. Internationally, there are good practices from where we can start, for instance the

Professional Standards for Teachers in England from September 20071

Introduction

Bringing coherence to the professional and occupational standards for the whole school workforce

- The framework of professional standards for teachers will form part of a wider framework of standards for the whole school workforce. This includes the Training and Development Agency for Schools’ (TDA) review of the occupational standards for teaching/classroom assistants and the professional standards for higher level teaching assistants in consultation with social partners and other key stakeholders and a review of leadership standards informed by the independent review of the roles and responsibilities of head teachers and the leadership group.

What these standards cover

- The framework of professional standards for teachers set out below defines the characteristics of teachers at each career stage. Specifically it provides professional standards for:

- the award of Qualified Teacher Status (QTS) (Q)

- teachers on the main scale (Core) (C)

- teachers on the upper pay scale (Post Threshold Teachers) (P)

- Excellent Teachers (E)

- Advanced Skills Teachers (ASTs) (A)

We can have a look at the complete guide to see what is at stake in this link: < www.tda.gov.uk >. [The Training and Development Agency for Schools (TDA) is the national agency and recognised sector body responsible for the training and development of the school workforce.] Another example from Australia (The Institute of Teachers of New South Wales):

The Framework of Professional Teaching Standards provides a common reference point to describe, celebrate and support the complex and varied nature of teachers’ work. The Professional Teaching Standards describe what teachers need to know, understand and be able to do as well as providing direction and structure to support the preparation and development of teachers.

Links:

- www.nswteachers.nsw.edu.au/IgnitionSuite/uploads/docs/Professional%20Teaching%20Standards.pdf

- www.nswteachers.nsw.edu.au/Main-Professional-Teaching-Standards.html

If we want to start evaluating teachers’ performance, we should learn in advance how to set a framework of professional standards, otherwise what we are evaluating is just standard educational behavior and not professional skills. Moreover, such direction should be taken only if the philosophy of evaluation is performance-based. 20

Current Portuguese teacher performance evaluation has two dimensions: functional performance – evaluated by the director of the school – and scientific-pedagogical performance – evaluated by the head of department.21 In any case, what is at stake for the current trend in Portuguese policies for in-service teachers is how do they perform, how do they act in class, how do they relate to each other and how do they integrate themselves with the educational community. Other criteria include performance related with curricular and extracurricular activities, regular attendance, positions in school bodies, participation in continuous education courses, and pedagogical relationship with students, and class observation, which is a crucial aspect of any teacher performance evaluation. 22

In the first place, such policy does not place performance evaluation under the supervision of current practicing classroom teachers in the same scientific area, as it should be in all circumstances – the school director or the head of department can be both from different areas and, eventually, a Portuguese Language teacher who does not have any habilitation in Foreign Languages teaching can indeed evaluate the performance of an English Language teacher, if he/she happens to be the head of department. This is just one of many hypothetical examples, but this situation should never be possible from any point of view. What counts for the Portuguese system of evaluation is that it has to work in administrative terms at any cost. No one can improve his/her own teaching from here. 23

In the second place, such policy needs a strong system of professional certification prior to any form of performance evaluation in a national framework. It is not by surprise that we see that the NBPTS planned their certification system for 20 years and stated that it “could never be established within the three-to-four-year timeline that many politicians face”.24 In the much confusing Portuguese system, everything is planned to have political results in less than four years and a national certification system is something that is disseminated through many different processes and institutions.

We are missing, in my view, teacher performance that is the result of effective teacher education: what is the nature of knowledge emerging in class? What is being taught? How teachers adapt knowledge to specific characteristics of students? How teachers deal with the learning environment they are working in? These are substantially different questions in teacher performance evaluation than those raised by the “Guia da Avaliação de Desempenho dos Docentes para o Ano Lectivo de 2008/2009”. If we are to make judgments about teachers’ effectiveness, we should not leave any of these questions behind, and we should also be able to integrate the indicators of teacher qualifications in our final evaluation. I guess that our law makers have forgotten that restructuring strategies in teacher education that are based on constructivist beliefs will always require a change in how knowledge is understood. We should not be only worried if a language teacher, for instance, is able to reduce failures in students’ scores, or able to integrate him/herself in school activities or able to fulfil all administrative work that is expected from him/her by school authorities, but we should pay attention to questions related to knowledge acquisition and knowledge teaching. Mimetic practices in class has been so widely used by teachers everywhere in all disciplines that an evaluation system should also promote ways to avoid those imitative processes of learning that have been institutionalized in classrooms – when learning is reduced to repetition, recitation, and reproduction of fixed forms of knowledge from the course textbook to the set of beliefs that a teacher is comfortable with and that are being used as the only source of knowledge.

In earlier stages, the Ministry of Education proposed using value-added testing models to determine teacher effectiveness, meaning that students’ academic results would be a practical demonstration of that effectiveness. It is impossible to prove that students’ high scores are a consequence of excellent teacher performance.25 Gigantic countries like China have recently taken a different course in this matter. China's Ministry of Education issued a notice “saying primary and high schools should not evaluate teachers’ performance by their student's passing rates at entry examinations. Passing rate has long been the decisive factor in judging school quality and teacher competency, which often resulted in teachers’ occupation of students' free time. Experts said the country's exam-oriented education system tends to neglect the cultivation of a well-rounded personality. Though schools have the final say on the work assessment, opinions from students and parents should also be incorporated into the whole evaluation, said the notice.”26

If we should disregard evaluating teachers’ performance by their student's passing rates, which is the alternative? Resuming Linda Darling-Hammond arguments, it is possible “to construct a system which incorporates multiple measures of teacher performance to identify highly effective teachers, including:

- Attainment of National Board Certification or superior performance on a teacher performance assessment, offered by the state or district, measuring standards known to be associated with student learning. Such standards-based teacher evaluations should include evaluation of teaching practices based on validated benchmarks conducted through classroom observations by expert peers or supervisors, as well as systematic collection of evidence about the teacher’s planning, instruction, and assessment practices, work with parents and students, and contributions to the school.

- Contributions to student learning and other student outcomes, drawn from classroom assessments and documentation, including pre- and post-test measures of student learning in specific areas, evidence of student accomplishments in relation to teaching activities, and analysis of standardized test results, where appropriate. The evidence should include a wide range of learning outcomes and take student characteristics into account.

Teachers eligible for master / mentor teacher designation should have met the Highly Qualified Teacher requirement under NCLB and have at least four years of successful teaching experience as evidenced by outstanding performance on regular teacher evaluations. These evaluations should be based on a portfolio of evidence about planning, teaching, and learning environments, as well as student learning, and classroom demonstrations of teaching excellence.”27

Merit has to be rewarded in any profession. The Portuguese Government recognizes that the current evaluation system allows the recognition of merit as a way to improve teacher performance in general.28 Apart from the promise that those teachers who have been evaluated through Government rules will be granted a certain position (?) in future national applications for the job, I do not see anything planned in this respect. The rewarding of merit in teacher performance cannot be reduced to career progression. An excellent teacher would expect something else once his/her excellence is officially recognized. Administrative compensation is just the easy way to publicize a resonating course of action but it is a poor design of a true policy. We can compare this policy with the agenda for education of the new administration in the USA, which declares from the beginning that “Obama and Biden will promote new and innovative ways to increase teacher pay that are developed with teachers, not imposed on them. Districts will be able to design programs that reward with a salary increase accomplished educators who serve as mentors to new teachers. Districts can reward teachers who work in underserved places like rural areas and inner cities. And if teachers consistently excel in the classroom, that work can be valued and rewarded as well.” 29 Teacher pay has been based almost entirely on seniority for the last 30 years in Portugal. We have a long way to change this path.

We have neglected to design a system for the evaluation of teachers that can be viewed as an accurate organization of all aspects involved in the profession. That could only be possible if the main objective would be educational rather than political. I will address the following aspects taking into consideration the description used by Michael J. Dunkin in his account of evaluation of teachers' effectiveness in Australia, where he states that:

There are five main preliminary matters involved in arriving at a system for the evaluation of teachers. The first is the purpose of the evaluation; the second is the target category of teachers to be assessed; the third is the conception of teachers' work that is adopted; the fourth concerns the dimensions of teaching quality about which judgments are to be made; and the fifth is the approach to establishing the validity of the assessments. 30

A. Purposes

We need to decide, prior to anything else, which type of evaluation we want to introduce in our system: A) Evaluation to encourage the professional growth and development of teachers; or B) Evaluation to select, graduate and hire teachers. It seems to me that anything else is expected from the current Portuguese system than promoting a system of evaluation that ignores growth-oriented methods that would affect all teachers instead of having a method that wants to identify and give merit to the best ones only. A language teacher, for instance, who depends so much of language competence and performance, needs an evaluation system that will help him/her to improve his/her skills. Language teachers are almost never satisfied with their linguistic performance and tend to feel an urgent and constant need for improvement. This has been a silence process, and it should not be so. Language teachers need feedback from more experienced teachers may be in a more frequent basis than any others. A national evaluation system has to take that into account.

B. Category of teachers to be assessed

I agree with Michael J. Dunkin’s conclusion that “issues and methods associated with teacher evaluation depend upon the stage of professional development attained by the teachers to be evaluated. Graduates of preservice teacher education programs seeking certification or licensing would not fairly have the same standards applied to them as would experienced teachers seeking promotion to senior teacher positions. Clearly, the assessment of preservice teachers would need to be considered separately from the assessment of novice, inservice teachers, who would need to be considered separately from experienced teachers seeking career awards, promotion or merit pay.” Instead of having parallel evaluation systems, we have now a three steps system that is entirely separate from each other: 1) pre-service evaluation (master courses at universities and polytechnics); 2) Professional access testing or “prova de ingresso” (undertaken after graduation and at the responsibility of the Ministry of Education); 3) Teacher performance evaluation (in-service evaluation at the responsibility of the Ministry of Education, but with no connection with the previous evaluations)31. Instead of promoting a culture of confidence in the profession and self-confidence in one’s performance, the Portuguese system promotes evaluation for an administrative purpose only, with no observation to true personal development.

C. Conceptions of teachers' work

Teacher’s work in Portugal is never conceived by politicians as a craft or an art but rather as a labour that needs to be regulated. Creativity and innovation, effective improvisation and unconventionality in class is almost never rewarded or even recognized neither by formal regulations nor by evaluators. Everything in the current teacher performance evaluation regulations tends to the accomplished performance of the teacher as referring to standardised forms of teaching. Portuguese teachers are expected to implement a national curriculum that has been designed for them, and then senior supervisors will make sure that that implementation agrees with every item pre-determined for their performance. The alternative model – when evaluation of teacher performance is conducted largely to ensure that proper standards of practice, including everything the teacher is adding to the benefit of instruction, are being employed − is not present.

D. Dimensions of teacher quality

We should take into consideration the three main dimensions of teacher quality: teacher effectiveness, teacher competence and teacher performance. According to Michael J. Dunkin’s summary: “Teacher effectiveness is a matter of the degree to which a teacher achieves desired effects upon students. Teacher performance is the way in which a teacher behaves in the process of teaching, while teacher competence is the extent to which the teacher possesses the knowledge and skills (competencies) defined as necessary or desirable qualifications to teach.”32 At this moment, Portuguese policymakers have adopted paper-and-pencil tests of knowledge for professional certification of those graduates who finish in-service education (teacher competence evaluated only); it has introduced for the first time observational tools for the evaluation of teacher performance for in-service professionals; and it has tried in its first version to introduce the assessment of teachers' effectiveness through student achievement scores. We lack a system that is capable of integrating all three dimensions in an adequate formula.

Moss distinguished between "psychometric" or "traditional" and "hermeneutic" approaches, on referring to "performance assessment".33 The Portuguese system has been developed under the belief that only a psychometric approach of single performances are valid, leaving aside extra knowledge about the teacher as a professional.34 In other words, what is evaluated is the teacher as an individual who can respond to administrative requirements and perform them correctly. The teacher as an intellectual performer is not taken into consideration. Moss explained the difference of both approaches as follows: “Regardless of whether one is using a hermeneutic or psychometric approach to drawing and evaluating interpretations and decisions, the activity involves inference from observable parts to an unobservable whole that is implicit in the purpose and intent of the assessment. The question is whether those generalizations are best made by limiting human judgment to single performances, the results of which are then aggregated and compared with performance standards [the psychometric approach], or by expanding the role of human judgment to develop integrative interpretations based on all the relevant evidence [the hermeneutic approach].” (p.8). We are missing this later approach to teacher performance education, where all dimensions of personal development of a teacher are considered and discussed, and not only his/her skills to perform knowledge transmission to young learners. Who is the teacher whose performance we are observing? – It seems to me that this simple question is being neglected.

We have already called attention to the fact that we do failed to define national guidelines and standards for pre-service and in-service teacher education. I see the tradition of countries like the USA as exemplary in this matter. Since 1967, The National Council of Teachers of English has published the Guidelines for the Preparation of Teachers of English Language Arts 35 which has been updated and revised at ten year intervals. Since 1987, NCTE has also published Standards for English Teacher Preparation Programs, derived from the Guidelines, which has been used by institutions seeking state accreditation and/or national accreditation through the National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE). According to the Conference on English Education, in his declaration titled: “Program Assessment in English Education: Belief Statements and Recommendations”, these documents “are representations of the profession’s values and beliefs about what constitutes essential knowledge, dispositions, and abilities of beginning English teachers and the features of the programs that lead to licensure for beginning English teachers, NCTE must be able to demonstrate that these Guidelines and Standards reflect a professional consensus among English teachers.” In this matter, our policymakers have a different view: “professional consensus” is something is impossible to obtain in four years – the ordinary lifetime of a policymaker −, therefore they have to work as the voice of the profession. In practice, the current teacher performance education system will treat the English teacher exactly the same way all other teachers as if teacher performance would be the same or as if all disciplines would lead to the same set of teaching behaviours. For example, NCTE is worried with multicultural schools and consequences for teaching and learning:

We believe that English education programs should provide candidates with broad opportunities to interact with students of diverse class, gender, ethnic, economic, social, academic, and physical abilities. Evidence of such experience should include, but are not limited to, reflective journals, lesson plans, case studies, videotaping, observations, and other artefacts which would support candidates’ professional development. 36

The multicultural aspect of classes in contemporary schools, which affects teacher performance in many ways, is being neglected by Portuguese policymakers. You will not read a word on this matter in any major official document about teacher evaluation in Portugal.

How should we evaluate language teachers’ performance if we lack guidelines about knowledge standards? In the USA, the NCTE has defined the following two main types of standards:

NCTE knowledge standards

Teachers of English Language Arts need to know the following:

- That growth in language maturity is a developmental process;

- How students develop in understanding and using language;

- How speaking, listening, writing, reading, and thinking are interrelated;

- How social, cultural, and economic environments affect language learning;

- The process and elements involved in the acts of composing in oral and written forms (e.g., considerations of subject, purpose, audience, point-of- view, mode, tone, and style);

- Major developments in language history;

- Major grammatical theories of English;

- How people use language and visual images to influence the thinking and actions of others;

- How students respond to their reading and how they interpret it;

- How readers create and discover meaning from print, as well as monitor their comprehension;

- An extensive body of literature and literary types in English and in translation;

- Literature as a source for exploring and interpreting human experience − its achievements, frustrations, foibles, values, and conflicts;

- How non-print and nonverbal media differ from print and verbal media;

- How to evaluate, select, and use an array of instructional materials and equipment that can help students perform instructional tasks, as well as understand and respond to what they are studying;

- Evaluative techniques for describing students’ progress in English Language Arts;

- The uses and abuses of testing instruments and procedures;

- Major historical and current research finds in the content of the English Language Arts curriculum.

NCTE pedagogical standards

Teachers of English Language Arts must be able to do the following:

- Select, design, and organize objectives, strategies, and materials for teaching English Language Arts;

- Organize students for effective whole-class, small-group, and individual work in English Language Arts;

- Use a variety of effective instructional strategies appropriate to diverse cultural groups and individual learning styles;

- Employ a variety of stimulating instructional strategies that aid students in their development of speaking, listening, reading, and writing abilities;

- Ask questions at varying levels of abstraction that elicit personal responses, as well as facts and inferences;

- Respond constructively and promptly to students’ work;

- Assess student progress and interpret it to students, parents, and administrators;

- Help students develop the ability to recognize and use oral and written language appropriate in different social and cultural settings;

- Guide students in experiencing and improving their processes of speaking, listening, and writing for satisfying their personal, social, and academic needs and intentions;

- Guide students in developing an appreciation for the history, structure, and dynamic quality of the English language;

- Guide students in experiencing and improving their processes of reading for personal growth, information, understanding, and enjoyment;

- Guide students toward enjoyment, aesthetic appreciation, and critical understanding of literary types, styles, themes, and history;

- Guide students toward enjoyment and critical understanding of non-print forms;

- Help students make appropriate use of computers and other emerging technologies to improve their learning and performance;

- Help students use oral and written language to improve their learning.

Some State Departments can develop these standards into a more complex framework, like that adopted by the Indiana Department of Education, expanding each standard in three dimensions: performances, knowledge and dispositions. The appendix is most useful with Guidelines for Developing English/language arts Programs for Teachers of Early Childhood and Middle Childhood, Early Adolescence, Adolescence and Young Adulthood (AYA).37 Only after such a tradition is founded and implemented, one should consider integrating a system of teacher performance evaluation, choosing a model from a good international practice and adapting it to national idiosyncrasies.

In the English-speaking world, there are many exemplary models of teacher performance evaluation that could be used in Portugal. I will describe a few selected from good practices around the world.

1. Certificate in English Language Teaching to Young Learners (CELTYL) and Young Learner (YL) extension to the Certificate in English Language Teaching to Adults (CELTA) . Cambridge CELTA Assessment, for instance, includes two components of assessment:

Component One: Planning and teaching

In this component, candidates are required to practice teach for a total of six assessed hours, working with adult learners at a minimum of two levels in classes of the required size.

By the end of the six hours of assessed teaching practice, candidates should have demonstrated successful achievement of all the teaching practice assessment criteria.

Component Two: Classroom-related written assignments

This component consists of four written assignments.

The assessment criteria are known to candidates for every aspect of the whole process of evaluation. Performance evaluation includes a list of descriptors that are organized in two general objectives: “[candidates] prepare and plan for the effective teaching of adult ESOL learners”, and “[candidates] demonstrate professional competence as teachers”. The principles and criteria of CELTA assessment could easily be a starting point to proceed to teacher performance evaluation for in-service teachers, since they point at improving instruction, helping in gauging the quality of teaching, and encouraging professional improvement and growth. CELTA in itself is not a model for implementing a unique programme in continuous education, but I am referring to this kind of certification as an example of a good practice in teacher education, which includes a well-structured model of teacher performance evaluation. 38

Links:

2. A general purpose instrument of evaluation: Teacher Performance Evaluation (Jackson Public School District, Mississippi, USA) - The district has 59 schools: 8 high schools and a Career Development Center, 10 middle schools, 38 elementary schools, and 2 special schools. The handbook of this District in the USA has an introductory set of texts that give clear information on the philosophy of education, the philosophy of instruction and the philosophy of evaluation of the whole process of teacher performance evaluation. The purposes of teacher performance “are fivefold:

- to determine competence

- to assess strengths

- to provide support and mentoring

- to assure continued growth through differential experiences

- to monitor the organization’s employment decisions.”

Teachers have prior knowledge of performance areas, criteria and descriptors, which include the following groups:

- Productive teaching techniques

- Student achievement

- Organized, structured class management

- Positive interpersonal relations

- Employee responsibilities

A complete set of forms are included in the handbook, including forms for summative evaluation reports, instructional improvement plans, self-evaluation forms for teacher performance, students feedback, teacher-to-teacher feedback, and parent feedback.

Links:

In the English-speaking educational world, there are many other examples of guides to effective teacher performance evaluation. A common feature is the aspiration to improve the quality of instruction, professional growth, and improvement of overall job performance. This is also the case with the North-American Bedford County Public Schools’ teacher evaluation system, which39 starts with the identification of performance standards referring to the major duties performed by a teacher, includes teacher’s annual goals for improving student achievement, day-to-day observations and student surveys.

These examples are good practices that were not designed to work as extra-administrative work loaded to the teacher’s ordinary daily work. Such system of evaluation is seen as part of a culture of professional development that is accepted by educational communities as essential to teacher’s effectiveness.

Performance-based teacher evaluation is a professional development key-phase for all teachers. Teacher evaluation of pre-service teachers works as a means of ensuring that they have or are developing essential teaching skills; in-service teachers are evaluated to ensure that teachers can evolve from that novice stage to proficient and expert stages. In a well-organized educational system, all teachers should have an annual professional development plan approved by the administration of the school they have a contract with. A national and all-purpose regulation has to exist, providing that the focus of teacher performance evaluation is the improvement of individual professional development, teaching practices and teacher effectiveness. Job descriptions and evaluation forms must have specific performance criteria and standards, from where all phases of evaluation must be taken from. Decision-making is based on both classroom observation and teacher documentation on standards not observed. Self-evaluation and reflection are included. The ideal model is designed to assist in implementing both professional development plans and professional improvement plans.40 Specific forms of performance-based teacher evaluation should be designed to meet the characteristics of foreign language teachers, which are necessarily different from general or all-purpose forms of teacher performance evaluation.

1 The original “Open Letter to the American People”, A Nation at Risk - The Imperative For Educational Reform, is available at: < www.ed.gov/pubs/NatAtRisk/index.html > (consulted on March 2009).

2 See Assessing Accomplished Teaching – Advanced-Level Certification Programs, National Research Council of the National Academies, Washington: The National Academies Press, p. 15.

3 See, for instance, my paper "Que professores vamos formar?" (2007), where I discuss all iniquities in detail. The paper is available on my website at: < www.fcsh.unl.pt/docentes/cceia >.

4 See the European Profile for Language Teacher Education – A Frame of Reference (available at: < www.lang.soton.ac.uk/profile/report/MainReport.pdf >) and the European Profile for Language Teacher Education – Final Report (available at: < http://ec.europa.eu/education/languages/pdf/doc477_en.pdf >), both written by Michael Kelly and Michael Grenfell, et alii: “This report proposes a European Profile for language teacher education in the 21st century. It deals with the initial and in-service education of foreign language teachers in primary, secondary and adult learning contexts and it offers a frame of reference for language education policy makers and language teacher educators in Europe.” (Final Report, p. 9). This Report to the European Commission, Directorate General for Education and Culture, could help reformatting our current policy towards language teacher education. I insist that we need a frame of reference covering all aspects of this type of professional education prior to any system of teacher performance evaluation.

5 See, as an example, the master offered at Instituto Politécnico de Castelo Branco: < www.ese.ipcb.pt/files/cursos/mestrado_1_ciclo.pdf > .

5 See the following example, taken from the same institution: < www.ese.ipcb.pt/files/cursos/mestrado_1-2_ciclo.pdf >.

6 This type of M. Ed. course is designed “for students who have an undergraduate degree in and who may or may not be certified to teach a foreign language.” < www.education.umd.edu > – consulted on April 2009.

7 This type of MEd expects candidates “to have obtained a first degree in a relevant subject (education, languages, linguistics, etc) equivalent to at least a UK Second Class Honours.” and “to have a minimum of two years full time relevant teaching experience.”

< http://education.exeter.ac.uk/course_information.php > – consulted on April 2009.

9 The organization of such courses does not depend on a rigid law act (as it is the case of Portugal and Law Act 43/2007), and this way it is possible to combine theses courses in a very flexible manner: “The Centre for Applied Linguistics offers a range of MA degrees. Each MA has its own specialist components, whilst sharing a number of modules with other MA degrees. Four degrees are available only to applicants who have a minimum of two years of full time teaching experience or the part-time equivalent (MA in ELT, MA in ELT for Specific Purposes, MA in ELT to Young Learners, MA in British Cultural Studies and ELT). One degree is specifically designed for those who have little or no substantial experience and who are at an early stage in their teaching career (MA in English Language Studies and Methods.) One degree is open to either group (MA in ELT and Multimedia). All of the degrees are usually taken as full-time courses over a period of twelve months but can also be completed part-time over a maximum of four years. It is possible to study for a Postgraduate Diploma or a Postgraduate Certificate within these courses (except the MA in Research Methods).”(Available at: < www2.warwick.ac.uk/study/postgraduate/courses/depts/applied-linguistics/taught >, – consulted on April 2009).

10 See link in previous note.

11 From the published bibliography, I recommend the paper “Research-based teacher education for multicultural contexts”, by Judith Bernhard, Carlos Diaz and Ilene Allgood, where they focus on a graduate program in education that “sought to prepare graduate students to address the needs of ELL students. Among the articulated goals of the program grant were that teachers enrolled would be able to: (1) use effective English for Speakers of Other Languages and bilingual educational strategies and methods; (2) use findings from testing, assessment and research functionally; and (3) promote multilingualism, and, in a broader sense, respect and equitable treatment of the heritages of home languages.” (Intercultural Education, Volume 16, Number 3, August 2005, p. 263). It is useless to compare these goals with those inscribed in DL 43/2007, which is a law that entirely disrespects the dimension of research-based teacher education.

12 “Future challenges for education and learning outcomes”, available at: < http://spica.utv.miun.se/wingspan/article.lasso?ID=WSA10018 > – consulted on April 2009.

13 The complete quote in Portuguese: “… o novo sistema de atribuição de habilitação para a docência valoriza, de modo especial, a dimensão do conhecimento disciplinar, da fundamentação da prática de ensino na investigação e da iniciação à prática profissional.” (p. 1321).

14 See “Guia da Avaliação de Desempenho dos Docentes para o Ano Lectivo de 2008/2009”, available at: < www.min-edu.pt >, – consulted on April 2009.

15 [In] 2006, 50,000 teachers throughout the country have achieved advanced certification through the National Board for Professional Teaching Standards. Since 1987 more than 55,000 teachers have achieved National Board Certification. That’s 55,000 teachers working side-by-side with administrators and fellow colleagues, tackling the challenges in today’s classrooms. “NBPTS is an independent, nonprofit, nonpartisan and nongovernmental organization. It was formed in 1987 to advance the quality of teaching and learning by developing professional standards for accomplished teaching, creating a voluntary system to certify teachers who meet those standards and integrating certified teachers into educational reform efforts.” < www.nbpts.org/about_us > – consulted on April 2009.

16 Decreto Regulamentar n.º 3/2008 (< http://min-edu.pt >). The so-called Portuguese National Jury is at this moment a mysterious entity, but, from what is known, it will hardly be compared to the American NBC, introducing themselves as follows: “National Board Certification is developed by teachers for teachers, with teachers heavily involved in each step of the process from writing standards, designing assessments and evaluating candidates. A National Board certificate attests that a teacher was judged by his or her peers as one who is accomplished, makes sound professional judgments about students, and acts effectively on those judgments. It allows teachers to gauge their skills and knowledge against objective, peer-developed standards of advanced practice. Offered on a voluntary basis, National Board certification complements, but does not replace, state licensing. While state licensing systems set entry-level standards for novice teachers, National Board certification establishes advanced standards for experienced teachers. National Board certification raises the quality of the teaching profession. It creates a high standard for the profession and the process itself offers high quality professional development. It is based on teacher self-reflection and inquiry, linked to the teacher's own teaching situation and practice. Accomplished teachers form the core of the teaching profession. Their knowledge and leadership are central to any effort to educate each of our students to high academic standards. The NBPTS has confirmed with the U.S. Department of Education that NBCTs do meet the definition of a "highly qualified teacher" as defined in the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB).“ < www.nbpts.org/about_us/mission_and_history/history > – consulted on April 2009.

17 See “Padrões de Qualidade para a Formação Inicial de Professores” (Deliberação 1488, INAFOP 2000; DR de 15-12-2000, 2ª série). INAFOP was closed in 2002 (n.º 2 do artigo 2.º da Lei n.º 16-A/02, de 31 de Maio).

18 Available at: < www.nbpts.org/the_standards > – consulted on April 2009.

19 See < www.fcsh.unl.pt/docentes/cceia/projectos/teals-teacher-education-and-applied-language-studies > >.

20 See Linda Darling-Hammond’s comment on the fact that the NBPTS values this type of evaluation as the best approach to success: “Another important attribute of the National Board standards is that they are performance-based: that is, they describe what teachers should know, be like, and be able to do rather than listing courses that teachers should know take in order to be awarded a license. (…) This approach aims to clarify what the criteria were for a determination of competence, placing more emphasis on the abilities teachers develop than the hours they spend taking classes.“ (“Reshaping Teaching Policy, Preparation, and Practice: Influences of the National Board for Professional Teaching Standards”, in Assessing Teachers for Professional Certification: The First Decade of the National Board for Professional Teaching Standards, Volume 11 of the book series: Advances in Program Evaluation, edited by Lawrence Ingvarson and John Hattie, Elsivier, Oxford, 2008, p. 32).

21 See the current Guide published by the Ministry of Education: Guia da avaliação de desempenho dos docentes para o ano lectivo de 2008/2009, in < www.min-edu.pt >.

22 See this particular guide for Professional Development for Language Teachers: Strategies for Teacher Learning, published by Jack C. Richards and Thomas S. C. Farrell, where several ideas are proposed to implement a strategic approach to all aspects of teacher development, and where class observation is seen as providing “a chance to see other teachers teach, it is a means of building collegiality in a school, it can be a way of collecting information about teaching and classroom processes, it provides an opportunity to get feedback on one’s own teaching.” (Cambridge University Press, New York, 2005, p. 86). Peer observation is a key factor in teacher performance evaluation, but it will only be effective if it helps the teacher to develop his/her own skills and professional awareness.

23 Much different is the policy adopted by the American NBPTS: “Another policy of NBPTS that was of paramount importance in persuading teachers to ‘trust’ the NBC process was the decision that all assessors who were judging candidate performances and other submissions within the assessment had to be current practicing classroom teachers within the certificate field of the candidates whose performances were being assessed.” (Assessing Teachers for Professional Certification: The First Decade of the National Board for Professional Teaching Standards, Volume 11 of the book series: Advances in Program Evaluation, edited by Lawrence Ingvarson and John Hattie, Elsivier, Oxford, 2008, p. xix).

24 Ibid., “Introduction”, p. 3. Note that certification here means: “an endorsement by a professional body that a member of that profession has attained a specific set of advanced performance standards. Application for NBPTS advanced certification is usually voluntary and available to all members of the profession (who have to have at least three years of experience in the profession). It is based on assessment of performance; it is not an academic qualification, or a record of professional development courses attended. (...) Most important, it acknowledges that the individual who gains this certification is demonstrably teaching at highest levels in our profession.” (Idem).

25 Linda Darling-Hammond, Charles E. Ducommun Professor at the School of Education, Stanford University, concluded that evaluating teachers based on value-added student achievement test scores is a good research tool but one with “severe limitations as a primary means for evaluating individual teachers”. The reasons are listed as follows: “Teachers’ ratings are affected by differences in the students who are assigned to them (...); VAM [Value-Added Models] models do not produce stable ratings of teachers (...); most teachers and many students are not covered by relevant tests (...); many desired learning outcomes are not covered by the tests (...); it is impossible to fully separate out the influences of students’ other teachers, as well as school conditions, on their apparent learning (...) Thus, while value-added models are useful for looking at groups of teachers for research purposes – for example, to examine the results of professional development programs or to look at student progress at the school or district level – and they might provide one measure of teacher effectiveness among several, they are problematic as the primary or sole measure for making evaluation decisions for individual teachers.” (Full report available at: “A Proposal for Measuring and Recognizing Teacher Effectiveness”, < www.ewa.org/library/site/linda_darlinghammond_letter.doc >, consulted in March 2009).

26 Published on 6-2-2009, available at: < www.study-in-china.org/hostschools/educationoutlook/20092699504155.htm >, consulted on March 2009.

27 Linda Darling-Hammond, op. cit.

28 “A avaliação do desempenho docente é fundamental para o desenvolvimento profissional dos professores e, desse modo, para a melhoria dos resultados escolares, da qualidade do ensino e da aprendizagem e para o reforço da confiança das famílias na qualidade da escola pública. A avaliação de desempenho inscreve-se num conjunto de medidas de valorização da escola pública, como a introdução do inglês no 1º ciclo, a escola a tempo inteiro ou as aulas de substituição. Permite ainda reconhecer o mérito dos melhores professores, servindo de exemplo e de incentivo para a melhoria global do exercício da função docente em cada escola.”, available at: < www.min-edu.pt/np3/2833.html >, consulted on March 2009. A Law Act published in 1998 (Decreto-Lei nº 1/98, de 2 de Janeiro) already mentions merit in teacher performance, but in practice no one has ever been granted a reward of any kind for being an excellent teacher in a public school.

29 < www.whitehouse.gov/agenda/education >, consulted on March 2009.

30 See Dunkin, Michael J. (1997): "Assessing teachers' effectiveness”, Issues in Educational Research, 7(1), pp. 37-51, available at: < www.iier.org.au/iier7/dunkin.html >, consulted on March 2009.

31 In his article, Michael J. Dunkin (1990) describes R. J. Stiggins and D. L. Duke proposal in The Case for Commitment to Teacher Growth: Research on Teacher Evaluation (State University of New York Press, New York), who “suggested three, parallel evaluation systems. The first would be an induction system for novice teachers with a focus on meeting performance standards in order to achieve tenure, using clinical supervision, annual evaluation of performance standards and induction classes, with mentors and a recognition of similarities in performance expectations for all. The second would be a remediation system for experienced teachers in need of remediation to correct deficiencies in performance so that they might avoid dismissal. This would involve letters of reprimand, informal and formal, planned assistance by a remedial team and clinical supervision. The third would be a professional development system for competent, experienced teachers pursuing excellence in particular areas of teaching. These would be teachers pursuing continuing professional excellence. They would be involved in goal setting, receive clinical supervision, and would rely on a wide variety of sources, such as peers, supervisors, students and themselves for feedback, and would recheck their performance standards periodically. They would respond to the different demands for performance by different grade levels and subject areas.” (op. cit.). This is good planning for an integrated system of evaluation; on the contrary, the Portuguese system is totally disintegrated and planned for the satisfaction of each level of teacher education and not for whole system.

32 Op. cit.

33 Moss, P. A. (1994): “Can there be validity without reliability?”, Educational Researcher, 23 (2).

34 The evaluation philosophy adopted by the Law Act “Decreto Regulamentar n.º 3/2008” is best understood if we think of what Good and Mulryan invoke as biased criteria for teacher performance evaluation which is aimed at obtaining a certain professional rating only: “[T]he key role for teacher ratings in the 1980s is to expand opportunities for teachers to reflect on instruction by analytically examining classroom processes. For too long rating systems ... delineated what teachers should do and collected information about the extent to which they did it, Ratings of teacher behavior should be made not only to confirm the presence or absence of a behavior but with the recognition that many aspects of a teaching behavior are important (quality, timing, context) and that numerous teacher behaviors combine to affect student learning.“ (“Teacher ratings: A call for teacher control and self evaluation”, in J. Millman & L. Darling-Hammond (eds.) (1990): The New Handbook of Teacher Evaluation: Assessing: elementary and secondary school teachers, Newbury Park, CA, p.208).

35 Original document available at: < www1.ncte.org/library/files/Store/Books/Sample/Guidelines2006Chap1-6.pdf >, consulted on March 2009. The advert of the NCTE website reads as follows: “The 2006 version of the Guidelines, prepared by the NCTE Standing Committee on Teacher Preparation and Certification, outlines the basic foundational elements of an effective English teacher preparation program and describes how English teacher preparation programs might provide support for candidates when they graduate into their own classrooms.”

36 See: < www.ncte.org/cee/positions/programassessment >, consulted on March 2009.

37 See < www.doe.in.gov/dps/standards/EnglishLangArtsContStds.html >, consulted on April 2009.

38 Note that CELTA is aimed at people with little or no previous experience of teaching. As it is normally advertised, it CELTA is “an ideal choice for people who are interested in becoming teachers of English as a foreign language and who want to gain an internationally recognised qualification. It also constitutes the first stage of the qualification required to enter Further Education ESOL teaching. The Cambridge CELTA certificate is widely regarded by potential employers as a good indicator of teaching quality.” (see < www.liv.ac.uk/elu/celta.htm >, consulted on April 2009). In itself, CELTA cannot be benchmarked with the Portuguese pre-service education system, which is a complete process in itself. CELTA is normally combined with other degrees, diplomas and certifications. We have several Cambridge-based practices and types of assessment and certification that could also be used as examples of good practices: the Teaching Knowledge Test (TKT) (“a test from Cambridge ESOL about teaching English to speakers of other languages. It aims to increase teachers' confidence and enhance job prospects by focusing on the core teaching knowledge needed by teachers of primary, secondary or adult learners, anywhere in the world. (...) After taking TKT, teachers who want to develop their knowledge further can progress to Cambridge ESOL's well-established Teaching Awards, such as ICELT and CELTA.”, see: < www.cambridgeesol.org/exams/teaching-awards/tkt.html>, consulted on April 2009; or the In-service Certificate in English Language Teaching (ICELT) (“ICELT is ideal if you are already teaching English in a specific context — e.g. teaching adults or young learners in the private sector, teaching within a university environment, teaching primary or secondary school learners. This qualification can help you to deepen your knowledge and develop your ability to reflect on and improve your teaching.”), see: < www.cambridgeesol.org/exams/teaching-awards/icelt.html > - consulted on April 2009.

39 Handbook available at: < www.bedford.k12.va.us/teacher/handbook.pdf > - consulted on April 2009.

40See, as a good example of this policy, the “Guidelines for Performance-Based Teacher Evaluation” used by the Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (available online at: < http://dese.mo.gov/divteachqual/leadership/profdev/PBTE.pdf >, consulted on April 2009).

Please check the Train the Trainer course at Pilgrims website.

Please check the How to be a Teacher Trainer course at Pilgrims website.

|