Pronunciation and Motivation in FLT: An Empirical Classroom Study Among Flemish Learners of German

Philipp Bekaert, Belgium

I’ve been terrorizing poor students of German (and of other foreign tongues too) with pronunciation exercises for quite a few years now. Many victims seemed to enjoy the terror, so now as a researcher and an assistant for German at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (Belgium) I’m trying to understand why. E-mail: philippbekaert@yahoo.de

Menu

Abstract

Introduction

1 Description of the experiment

1.1 The test sounds

1.2 The participating classes

1.3 Stage One: observation

1.4 Stage Two: first measurement

1.5 Stage Three: intervening in the teaching process

1.6 Stage Four: second measurement

2 The output data of the experiment

3 Discussion and conclusion

Bibliography

Refernce works

In spite of a growing interest for pronunciation among researchers, in everyday GFL classroom practice the importance of using a correct German pronunciation tends to be somewhat underrated by both teachers and learners. Beside suggesting reasons for this, the contribution offers a description of a pilot study carried out in six different GFL classes across Flanders and looks into the impact of systematic pronunciation instruction on the pupils’ actual performance. The contribution also discusses the problems encountered while implementing the study. Researchers involved in empirical studies have to make choices that may influence their output data; in this case, along with solving technical and human problems so as to guarantee the reliability of the output data, it had to be decided whether to conduct the study in different types of schools located in different dialectal areas, in larger towns and/ or in rural areas. The emphasis is on the importance of empirical studies and of reducing the number of variables.

Researchers on foreign language teaching (FLT), especially within the field of DaF (Deutsch als Fremdsprache, i.e. German as a foreign language or GFL), have shown a growing interest in pronunciation in recent years. In classrooms, however, the pronunciation of German still receives comparatively little attention – from both teachers and learners (Hirschfeld & Reinke 2007: 1). This seems to confirm observations I made during my former career as a German teacher in adult education (Bekaert 2009). These observations could be summarized as follows:

- Concerning their teachers, one of the points learners seem to be particularly critical about is the teacher’s so-called “Flemish accent” (the adjective Flemish refers here to the variety of Dutch – as the language is officially called in the Netherlands and Belgium – spoken in Flanders, i.e. Belgium’s northern Region; also, Belgian Regions are federate states, so education in Flanders is organized by the Flemish department of education), by which they mean the pronunciation of certain sounds. In parallel, most learners of German, adult ones at any rate, seem to appreciate their teacher to “sound like a native”

.

- Learners with a good German pronunciation seem to enjoy a kind of insider feeling, and that feeling seems to increase their motivation (see also Helbig et al. 2001: 872-873).

- Although Flemish adults are generally assumed to easily learn and fluently speak foreign languages, they often have considerable difficulties pronouncing some German sounds. It may be that these sounds exist in Flemish but are written differently in German, or that they are not found at all in Flemish, in which case adult Flemish learners of German often seem to fear appearing ridiculous or pompous if they try to imitate them.

- In many teachers and learners lacking self-confidence of this kind could lead to a tendency to dismiss pronunciation as something trivial and be satisfied with a poor pronunciation.

- Under certain circumstances pronunciation mistakes can lead to breakdowns in communication. I myself once witnessed how a native speaker understood täuschen (deceive) instead of tauchen (dive) only because his non-native interlocutor had wrongly realized the voiceless velar fricative [x] ( as an achlaut) in tauchen as a voiceless palatal fricative [ç] ( as an ichlaut) (see also Bekaert 2009).

It should be pointed out that these observations and speculations were purely intuitive at the time – hence the repeated use of the restrictive seem in the above. This is why I decided to investigate this matter further, and the first step in this investigation was a pilot study conducted in six different Flemish schools between January and April 2008. This pilot study was aimed at examining the importance given to pronunciation in the teaching of German as well as the pronunciation competence of the learners and a possible link to their motivation. The starting point of this experiment, on which we will now focus, was more empirical than theoretical, and the use of scientific literature on pronunciation problems is fairly limited.

This study was set up to investigate the pronunciation of five German sounds, which will in the following be called our “test sounds”:

- the voiceless palatal fricative [ç] (the so-called ichlaut as in ich);

- the voiceless velar fricative [x] (the so-called achlaut as in Achtung);

- the vocalized final as in vier Kinder (realized as fee-ah Kindah);

- the letter (pronounced as [ts]);

- the glottal stop (as in Not-arzt vs. Notar).

The last four of these sounds were chosen because in my teaching practice, they usually proved quite difficult to acquire by Flemish learners. There can be two reasons for this: either the sound is not current in Dutch (or in its Flemish variety), as is the case for the achlaut, vocalized and glottal stop, or the corresponding grapheme differs, like [ts] written in Dutch and in German, whereas the Dutch is pronounced like in English.

The ichlaut, on the other hand, was used as a contrast to the achlaut and expected to be pronounced easily by all Flemish natives – and actually it was: the few pupils who did not get the ichlaut right were children of non-Flemish origin, among them a Dutch national, who in accordance with the pronunciation in use in the Netherlands got his achlaut right, but not a single ichlaut (already described in Bekaert 2009).

Compared to other aspects of language acquisition, pronunciation is a phenomenon that has until now been somewhat neglected in academic teaching and research (Helbig et al. 2001: 873). Nevertheless, instructors and phoneticians usually seem to agree that pronunciation skills are best developed at a beginner level (see among others Moise 2007: 5 & 8; Helbig et al. 2001: 873 & 875). Learners otherwise risk – it is further assumed – to fossilize in their own mistakes (Selinker 1972; Helbig et al. 2001: 875-876). These mistakes are thought to be much harder to eliminate in later learning stages. Therefore it was decided that the experiment had to be carried out in beginner classes. Applied to the Flemish educational system, in which German is the third foreign language – after French and English –, this would mean, in government-run schools, in the fifth form of secondary education, with seventeen-year old pupils.

On the basis of a list, provided by the Flemish department of education, of all government schools offering courses of German in the fifth form, six classes from six different schools were eventually chosen, ensuring geographical diversity as all five Flemish provinces as well as rural and urban areas were represented. In total, 62 fifth-formers participated in the study:

- Class n°1: 22 pupils, 2 hours a week, ASO school (ASO = algemeen secundair onderwijs, i.e. grammar school) in a rural community of the province of East Flanders;

- Class n°2: 16 pupils, 2 hours a week, ASO school in a small town of the province of Flemish Brabant;

- Class n°3: 12 pupils, 3 hours a week, TSO school (TSO = technisch secundair onderwijs, i.e. secondary modern school or technical school) in a larger town of the province of Flemish Brabant;

- Class n°4: 10 pupils, 2 hours a week, ASO school in a middle-sized town of the province of West Flanders;

- Class n°5: 7 pupils, 2 hours a week, ASO school in a middle-sized town of the province of Limburg;

- Class n°6: 16 pupils, 3 hours a week, ASO school in a large city of the province of Antwerp;

One may wonder why the sum of pupils mentioned above makes 83, not 62. These were the pupils originally registered in each class. But as a matter of fact, it sometimes appeared surprisingly difficult to ascertain the exact number of pupils belonging to a given class, as a few of them would “come and go”. Moreover, all pupils absent at one of the last three stages of the study (as described in the following) had to be retroactively excluded from the final data. Along with them, one pupil was removed from the data because she was a native speaker of German. Ultimately, 62 pupils were taken into account for the final data.

The classes 3 and 6 had three hours of German a week instead of two. The Flemish curriculum of German requires that this third hour be spent on deepening knowledge acquired in the first two (cf. Leerplan AV Duits 2006: 8). This implies that all classes were, at least theoretically, and at least with respect to grammar and vocabulary, supposed to have reached comparable levels at any given time of the school year.

However, class 6 appeared to have used this extra time for a special pronunciation training right at the beginning of the school year. Admittedly, this proved quite interesting for my general hypothesis about the link between pronunciation and motivation, since the pupils of this class were generally above average in all domains of language acquisition – including pronunciation, as is clearly shown by the results of the first measurement (for further description of class 6 see Bekaert 2009). But this special pronunciation training also jeopardized the validity of the experiment, since class 6 started with an obvious advantage.

On the other hand, the other class with three hours of German a week, class 3, scored distinctly below average (which might also be explained by the different school type). As a matter of fact, the results of the first measurement show, if anything, that is it an illusion to expect any kind of homogeneity among participating classes.

The experiment lasted from the third week of January, after the pupils had completed their fourth month of German, until early April, i.e. shortly before the end of their first year of German. The experiment consisted of four stages, one to four weeks elapsing between one stage and the next.

It must be stressed that it was only upon completion of the fourth stage that both teachers and learners came to know what aspect of language acquisition was being dealt with. Had they known earlier that the study was about pronunciation, this would inevitably have influenced their behavior and performance with regard to pronunciation.

The first stage consisted of one observation hour in each class in order to assess to what extent German and Dutch were spoken in class, to what extent pronunciation was made an issue and if it was, how the pupils reacted to it. Also, it was attempted to assess how the teachers themselves pronounced the test sounds – but this succeeded only to a certain extent, since it was of course impossible to make the teachers specifically pronounce the test sounds without making them aware that the whole study was about pronunciation. Each observation hour was digitally (audio)recorded.

At the second stage of the experiment the pupils were called out of the classroom one by one during a German lesson and asked to read the following 21 sentences aloud (although the meaning of the sentences is irrelevant to the topic of this study a translation might appear convenient):

- Senta läuft auf den Zehenspitzen aus ihrem Zimmer.

(Senta tiptoes out of her room)

- Hast du vier Kinder?

(Do you have four children?)

- Sie haben nicht die ganze Nacht gesprochen.

(They haven’t talked all night long)

- Dieses Er/eignis hat sein Leben ver/ändert.

(This event has changed his life)

- Der Fußballspieler schießt ein Tor.

(The football player shoots a goal)

- Ich bin mit meiner Nichte ver/abredet.

(I have a meeting with my niece)

- Der Zahn/arzt hat mir von Kaffee mit Sahne abgeraten.

(The dentist has advised me against coffee with cream)

- Der Notar ruft einen Not/arzt.

(The solicitor calls an emergency doctor)

- Der Specht hat drei Löcher in den Baum geklopft.

(The woodpecker has made three holes in the tree)

- Die Pfadfinder wollen unter eigener Ver/antwortung ein Konzert ver/anstalten.

(The scouts want to organize a concert on their own responsibility)

- Ein belgischer Spruch lautet: „Eintracht macht Macht“.

(A Belgian saying runs: Unity makes strength)

- Die Herde bestand aus zwanzig Ziegen.

(The flock consisted of twenty goats)

- Wir ver/abschieden uns von der Einkaufs/abteilung.

(We are taking leave of the purchasing department)

- Falls Ihnen jemand im Wege steht, rufen Sie einfach: „Vorsicht!“

(In case somebody stands in your way, just shout: Careful!)

- Wir haben viel Zeit im Zoo verbracht.

(We have spent a lot of time at the zoo)

- Es ist unsere Pflicht, die Menschenwürde zu achten.

(It’s our duty to respect human dignity)

- Wir wollen uns den bayerischen Dialekt an/eignen.

(We want to acquire the Bavarian dialect)

- Hast du noch ein Buch für mich?

(Do you have another book for me?)

- Haben Sie Bücher für uns?

(Do you have books for us?)

- Willst du mit uns ins The/ater?

(Do you want to join us to the theater?)

- Erwin läuft im Zickzack.

(Erwin is zigzagging)

These sentences contain the five test sounds, which have been italicized in the above but quite obviously were not in the version that was presented to the pupils. After each sentence, pupils were asked to tell the interviewer if they had globally understood its meaning. This was in the first place meant to divert their attention from pronunciation, and for the sake of realism a few slightly more difficult sentences were included in the test. Every reading session was digitally (audio)recorded for later analysis of the test sounds. First the sounds that had been correctly pronounced would be counted per pupil. Afterwards a correct pronunciation rate for each class could be established per sound and subsequently for all sounds together.

This methodology implies that the pupils’ reading skills had to be relied on – knowing that this is not a perfect solution, but that a different methodology would have induced other problems. As a matter of fact, it repeatedly happened that sounds were mispronounced not because of failures in pronunciation, but as a consequence of misreading or misunderstanding parts of the (sometimes deliberately difficult) sentences. Some pupils pronounced, say, an achlaut instead of an ichlaut when reading “Bucher” instead of “Bücher” in sentence 19. Since the achlaut is expected after and the ichlaut after , the incorrect makes the following achlaut appear correct from a strictly phonological viewpoint. Yet these “logical errors” had to be considered mistakes in order to keep the statistics valid. Other mistakes, such as the omission of the glottal stop, can also be attributed to non-phonological factors: since the glottal stop occurs when a morpheme starts with a vowel pupils are due to omit it if they fail to recognize the morphemes that make up a compound word, as is likely to happen – especially by first-time reading in stressful circumstances – in words like Notarzt or verabredet. Again, this could not be taken into account without endangering the statistical analysis of the study, and these lexical or reading errors had to be counted as pronunciation mistakes. Also, when test sounds were not read at all, i.e. when what pupils read did not match the written text, the sound had to be rated as mispronounced.

In preparation of the third stage, the six classes were then divided in three – virtual – groups on the basis of the correct pronunciation rates obtained at stage two. Three classes belonged to group A (N = 44): class 2 (correct pronunciation rate 42,39 %), class 3 (correct pronunciation rate 23,98 %) and class 6 (correct pronunciation rate 54,53 %). Group B (N = 22) consisted only of class 1 (correct pronunciation rate 39,49 %), and group C (N = 17) included the classes 4 and 5 (correct pronunciation rate respectively 40,53 % and 47,42 %). The correct pronunciation rates and numbers of participants mentioned in this section were, at the time, provisional. Pupils who missed later stages of the experiment were subsequently removed from the final data.

The actual third stage of the experiment was a lesson, given by myself, on an arbitrarily chosen topic that fitted the teaching program: the possessive determiners. During preparations for that lesson I made sure that my sample and exercise sentences on possessive determiners contained repeated occurrences of the test sounds. During the actual class, most pupils quite expectedly failed to pronounce these sounds correctly, which on my part led to three – carefully prepared – reactions (for the terms explicit and implicit error corrections see Lochtman 2009):

- In group A pronunciation errors triggered explicit corrections and extended explanations about the underlying pronunciation mechanisms as well as about the differences between German and Dutch (or Flemish) pronunciation.

- In group B pronunciation errors triggered explicit pronunciation corrections (i.e. the word in question was repeated correctly, in some cases including a stress on the incorrect part), yet without any explanation about the underlying pronunciation rules.

- In group C the only reaction to errors consisted of implicit corrections. As in daily conversation, the whole sentence (i.e. a corrected version of it, adapted to the speaker’s viewpoint if necessary) is repeated by way of acknowledgement, with no particular stress on the incorrect elements of the original.

In this respect, group C was a test group that reflected a classroom situation not particularly focused on pronunciation. The groups A and B, on the other hand, were exposed to a more (for A) or less (for B) concentrated form of specific pronunciation teaching.

The fourth stage of the experiment consisted of a second measurement realized under similar circumstances and using the same sentences as in the second stage. This second measurement of the pupils’ pronunciation took place a few weeks after the “pronunciation lesson in grammatical disguise” and was aimed at investigating whether pupils performed better as a result of this intervention.

The objectivation of the sound ratings is an important question. Rating a sound as correct or mispronounced is something than can easily be disagreed upon (see Helbig et al. 2001:878). One way of enhancing the objectivity of this highly subjective business is an interrater reliability test ruling out all sounds whose rating is not sufficiently agreed upon by all co-raters (Bekaert 2009), but reducing the number of test sounds could, again, jeopardize the statistical validity of the study. The important thing was, after all, that all sounds of the first and of the second measurement be rated using the same criteria, and the best way to achieve this was probably to have them rated by the same person – ideally also the person who taught some of the classes pronunciation rules at the third stage of the study, i.e. myself. This is why I did all ratings myself, endeavoring to apply the same criteria to all of them.

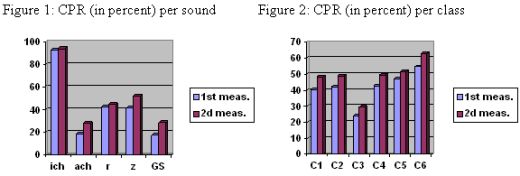

The final output data of the study is depicted below in terms of correct pronunciation rate (CPR) per sound (figure 1) and per class (figure 2):

The participating classes were classified randomly, so it is a mere coincidence that in figure 2 their performances rank from 1 up to 6 – the only exception being class 3, which brings us to the next point. It proved a mistake to include a technical school in the study: both school types are obviously very different, as is shown by the below-average performance of class 3.

Both figures above show a general improvement for all test sounds from the first to the second measurement – even more clearly so for the achlaut, the and the glottal stop. It is fair, however, to assume that any class will make progress in any particular domain of language acquisition in a three-month period. In order to determine if this improvement can be attributed to the disguised pronunciation teaching to which some pupils were submitted, we should examine the separate achievements (in percent) of the groups A, B and C. In figure 3 (below) A- stands for group A without class 3, as we have seen that the markedly below-average performance of class 3 has a noticeable impact on the final results.

Figure 3: CPR (in percent) per group

The difference between the two measurements, i.e. the increase in correct pronunciation rates, can be expressed in relation to the full 100 percent of sounds pronounced (as shown in figure 4) or as related to the correct pronunciation rate obtained by each group at the first measurement (figure 5):

Nota bene: At the first measurement, group C was the group with the highest correct pronunciation rate – at least if class 3 was taken into account, thus lowering the performance of group A. In both figures above, group C registers the lowest increase in correct pronunciation rate between the first and the second measurement. One could expect a group that is better at the start not to improve its performance to the same extent as the others. This comparatively low improvement also seems logical for group C as a test group that was exposed to no particular pronunciation instruction at stage three. But if the latter is true, i.e. if pronunciation instruction is assumed to have an impact on the actual performance of the pupils, then one should, in parallel, expect group A (which benefited from explicit corrections and in-depth explanations about pronunciation rules in German) to be the group with the highest increase in its correct pronunciation rate, followed by group B (which received only explicit corrections, without any explanation of rules). This, however, is not the case. With or without class 3 included in group A, it is group B that scores the highest increase in correct pronunciation rate, both in terms of absolute percentage and in relation to the first measurement.

It appears difficult to determine with certainty whether the slightly better performance of the groups A and B as compared to C can be attributed to the single factor of their exposure to pronunciation corrections (and explanations in the case of A) during stage three. Too many other potential factors remain uncertain.

First, the difference in performance between group C and the other two groups is probably too tiny to tell us anything definite, considering how volatile this kind of measurement can be. This volatility is best illustrated by an interesting incident that occurred during the second measurement. Because it was believed that the first recording had failed, one pupil of class 2 was recorded twice. When the first recording was eventually recovered, the two versions compared as follows (figure 6):

Figure 6: Same pupil recorded twice

If two recordings of the same pupil, taken the same day, at less than an hour interval, and of course carefully rated according to the same criteria, can show such perceptible differences, it becomes quite obvious that, statistically speaking, only a very large number of participants will allow to compensate for this human variation and to make valid statements about the possible impact of pronunciation instruction.

Second, as explained above, it proved a mistake to include a technical school in the study, and in a more general way, it proved a mistake to include too many different kinds of variables in this study, such as pedagogical or geographical diversity of the participating schools. The original idea was that all Flemish provinces should be represented so as to compensate for the potential phonological closeness between certain Flemish dialects and German (Bekaert 2009). As a matter of fact, class 4 appeared to score much better than other classes on the achlaut at the first measurement. Further research could determine whether this is due to the presence of some achlaut-like sound in the local dialect, but in the meanwhile, instead of enhancing the representativity of the output data, the geographical diversity of schools introduced a disturbing variable.

Similarly, the experiment included rural as well as urban areas, because it was assumed that pupils with a migration background would be more numerous in urban areas, and that this – presumably multilingual – background might positively influence their phonetical flexibility for German. In fact, all these precautions to make the study as representative as possible appeared to a large extent irrelevant. Neither were children with a migratory background more numerous in cities than they were in the countryside, nor did they perform noticeably better on pronunciation (Bekaert 2009). Actually, it could even be that their German was more negatively influenced by Flemish phonetics than in pupils from exclusevily Flemish-speaking families. If this were to be confirmed, later research would have to show why Flemish children “get their native phonetics more easily out of the way” than pupils for whom Dutch is the educational, but not the native language.

And third: Is pronunciation to be taught in an hour? And can any results be expected from that single hour when the pupils are tested almost a month later? In parallel, if pronunciation is to be taught only in the long run, isn’t the role of the regular teacher of great importance? In order to prevent the teachers from discovering too early what the whole experiment was about, the latter could neither be thoroughly screened on pronunciation nor asked to read the 21 test sentences themselves. Yet it must be borne in mind that the teacher is a capital source of pronunciation input to the learners, and this implies that a very influential factor had to remain unexamined here as well.

In future research it would therefore be advisable to reduce the amount of pedagogical and geographical variables, to extend the period of pronunciation teaching and maybe even the number of participants. At any rate, all study data presented here have to be seen in the light of these reservations.

Should a significant increase in correct pronunciation rate between the first and the second measurement become noticeable in such circumstances, then everything would plead in favor of making pronunciation an issue in Flemish GFL classes. If anything, this experiment has shown the importance of empirical classroom research in FLT studies and the importance of pilot studies of this kind in the empirical research process. They can save researchers much trouble during the conduction of their actual experiments.

Bekaert, Ph. (2009), Aussprache und Motivation im DaF-Unterricht: Probleme bei der empirischen Forschung. In Lochtman, K. & Müller, H.M. (Hg) Sprachlehrforschung. Festschrift für Prof. Dr. Madeline Lutjeharms (S.153-164). Bochum: AKS-Verlag.

Helbig, G., Götze, L., Henrici, G. & Krumm, H.-J. (Hg) (2001), Deutsch als Fremdsprache. Ein internationales Handbuch. Berlin/ New York: Walter de Gruyter.

Hirschfeld, U. & Reinke, K. (2007), Phonetik in Deutsch als Fremdsprache: Theorie und Praxis – Einführung in das Themenheft. Zeitschrift für interkulturellen Fremdsprachenunterricht, 12,2, http://zif.spz.tu-darmstadt.de

Lochtman, K. & Lutjeharms, M. (2004) Attitüden zu Fremdsprachen und zum Fremdsprachenlernen. In Börner, W. & Vogel, K. (Hg) Emotion und Kognition. Tübingen: Narr, 173-189.

Lochtman, K. (2004) Attitüden zu Fremdsprachen und zum Fremdsprachenlernen. In Börner, W. & Vogel, K. (Hg) Emotion und Kognition. Tübingen: Narr, 173-189.

Lochtman, K. (2009), Die 'geheimen Verführer' im DaF-Unterricht. Zur Rolle der impliziten mündlichen Fehlerkorrektur in der pädagogischen Interaktion. In Lochtman, K. & Müller, H.M. (Hg) Sprachlehrforschung. Festschrift für Prof. Dr. Madeline Lutjeharms (S.53-65). Bochum: AKS-Verlag.

Moise, M. I. (2007), Interferenzprobleme rumänischer Deutschlernender. Spezifische Aspekte der Ausspracheschulung und Aussprachekorrektur im Erwachsenenunterricht. Zeitschrift für Interkulturellen Fremdsprachenunterricht 12,2, http://zif.spz.tu-darmstadt.de

Ramers, K.-H. (2001), Einführung in die Phonologie, 2. Auflage, München: Wilhelm Fink Verlag.

Rasier, L. & Hiligsmann, Ph. (2007), Prosodic transfer from L1 to L2. Theoretical and methodological issues. Nouveaux cahiers de linguistique française, 28, 41-66.

Selinker, L. (1972), Interlanguage. International Review of Applied Linguistics, 10, 209-231.

Deutsches Universalwörterbuch CD-ROM (2006). Bibliographisches Institut & F. A. Brockhaus AG.

Leerplan AV Duits ASO derde graad eerste en tweede jaar (leerplan nr. 2006/041), Brussel: Departement Onderwijs – Ministerie van de Vlaamse Gemeenschap, 11.

Please check the Pronunciation course at Pilgrims website.

|