The Arts and Crafts of Teaching Pronunciation: The What and How?

Hande Isil Mengu, Turkey

Dr. Hande Isil Mengü is the Head of Teaching Units Coordinator at Bilkent University School of English Language in Ankara, Turkey. Over the years, she has been involved in teaching, course design and development, research work, teacher and trainer training and has tutored on the Cambridge-ESOL DELTA courses and MA courses. E-mail: hmengu@bilkent.edu.tr

Menu

Abstract

Introduction

Background to the study

Data collection

The package

Conclusion

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

References

This article reports on a study carried out with 45 Turkish students studying English at the preparatory program of an English medium university in Turkey regarding their feelings about pronunciation and the package they were ‘exposed to’ that helped them change their perceptions and improve their pronunciation.

Throughout history there has been a strong need to express words clearly and time has shown that even the simplest mistake in pronunciation has led to the loss of life as well as great confusion. Therefore, if we are to be effective in this world, we must speak clearly and precisely. It is a known fact that as students’ and teachers’ awareness of the importance of intelligible speech increases, pronunciation automatically finds room for itself in the classroom context and becomes an integral part of all classes. Therefore, especially in a non-English speaking environment (i.e. EFL setting) raising awareness of the importance of pronunciation plays a vital role in persuading students to believe in the miracles of pronunciation. To this end, the following are the questions upon which the study and the package were constructed:

- What is the best way to raise students’ awareness of the importance of pronunciation to help them improve their pronunciation?

- How can students be shown/persuaded that it is possible to articulate sounds correctly with a bit of practice?

- How can students see that certain sounds, for example, /w/ exists in Turkish (e.g. kavun, kavuk, tavuk etc.)?

In addition, the existence of the positive impact of pronunciation on “listening and reading comprehension”, “spelling” and “grammar” have been revealed through various studies in the area. That is why students’ awareness regarding the importance of pronunciation should be raised from day one. In any given context, as is known, the best way of raising awareness is achieved through unearthing where individuals’ beliefs centre on, which in this study was firstly realised through the initial administration of the beliefs questionnaire. Secondly, with the help of individual interviews the underlying cognitive and affective reasons behind the students “not so positive attitude” towards pronunciation was further explored. Thirdly, students were given the chance to self-assess their own articulation of the most common problematic sounds for Turkish learners to see where they were at and to give them a goal to work towards. Next, they had nine weeks of input and practice (i.e. the package) aimed to improve their pronunciation. Finally, the change in the students’ beliefs and the improvement in their pronunciation observed through their in and outside class work was validated through the final administration of the beliefs questionnaire. This was followed by a final round of interviews and a final phase of self-assessment for the students to concretely see the improvement in their pronunciation.

The students who took part in the study were students studying at the preparatory program of an English medium university to pursue their academic studies in the departments whose ages ranged from 17 to 22 (25 female and 20 male students). Most of them were false beginners who had limited exposure to English through classes taken at secondary school. It was certain that they had not done any work in the area of pronunciation previously and therefore it was a perfect opportunity to help them see the importance of pronunciation, knowing that it would have a lot of impact on their overall language skills. They were going to receive 20 hours of input and practice in the areas of grammar, vocabulary, lexis and discourse, and language skills (reading, listening, writing, speaking) over nine weeks at elementary level and were going to spend 5 hours every week working on pronunciation.

As mentioned previously the data collection stage consisted of the following phases:

Phase 1- Awareness Raising

- Initial admiministration of the beliefs questionnaire

- Initial round of semi-structured interviews

- Pre-test: Student self-assessment 1 (through software)

*Students received input and practice over nine weeks

Phase 2 – Observation of the Changes (in regards to perceptions and performance)

- Final administration of the beliefs questionnaire

- Final round of semi-structured interviews

- Post test: Self-Assessment 2 (through software)

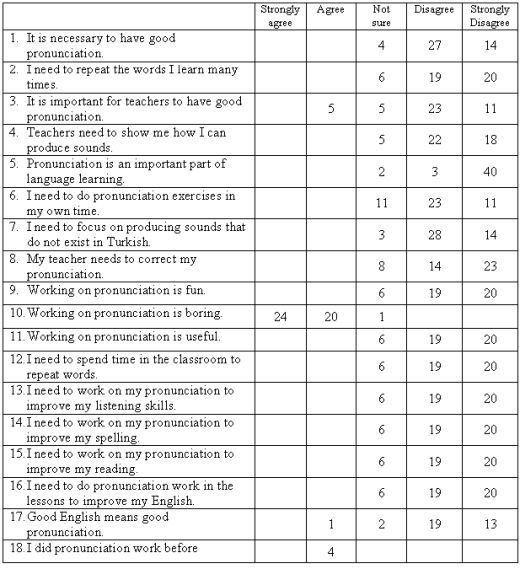

The first phase in the data collection stage started with the administration of the initial beliefs questionnaire (please see Appendix 1). The results were mainly “not so positive” as most of them did not believe in the importance of pronunciation as was revealed through their responses in the questionnaire (please see appendix 1). Therefore, there was a need to further explore the underlying beliefs of the students through the initial round of semi-structured individual interviews with randomly selected 15 students. During the interviews when asked questions about their resistance, the students gave the following responses (translated from their responses in Turkish):

“I have more important things to worry about like exam practice.”

“I can never produce these sounds, it is impossible.”

“I think it is silly to repeat words.”

“I find pronunciation activities very childish.”

“Why should I try to speak like native speakers I am Turkish.”

“I don’t think it is important because it is not tested in the exams.”

“I think the phonemic script is very difficult to learn.”

“Pronunciation does not help anything. It is a waste of time to spend class hours on pronunciation.”

“It is the most difficult part of learning English because native speakers swallow the word and I cannot understand anything.”

“I sometimes cannot differentiate the words/sounds native speakers use. I need to see how they articulate these sounds.”

Although most of the responses did not sound very positive, there was still hope. There were very strong feelings and beliefs that could only be tackled through self-assessment where students would record themselves (i.e. the waveforms of the sounds they produced through the soundforge software) and compare it against the acceptable articulation of the sound to see if they were able to articulate the most common problematic sounds (i.e. /θ/, /ð/, /ŋ/, /w/, /æ/) that had been previously identified through research and classroom observations. This served as proof for the need to do work on pronunciation in the classroom and helped raise awareness on the part of the students as most of them had difficulty in articulating the problematic sounds. They were very engaged throughout the self-assessment stage and were eager to try over and over again to see if they could produce the sounds correctly, which meant constant repetition of the sounds and helped them see the importance of ‘drilling’ in the process. This marked the end of the first phase, that is, the awareness raising stage.

Having completed the awareness-raising stage successfully, the students were ready for the package which consisted of the following stages and components:

Duration: 9 weeks (45 hours in total – 5 hours of input and practice every week)

Weeks 1-6: Initial presentation/focus on the sounds (30 hours in total)

- Awareness raising (importance of pronunciation work/ introduction to the phonemic script/transcribing/dictionary work)

- Lessons on pronunciation (please see appendix 3 for the lesson framework):

- 4 hours every week in class (36 hours)

- Focus on audiovisual representation of how the sounds are articulated

- Practice activities (sounds/stress/intonation/connected speech) through the practice software (1 hour in the computer lab every week – 9 hours)

- Games (for further reinforcement)

Weeks 7-9: Follow-up work/remedial teaching (15 hours in total)

Throughout the nine weeks, the students were actively engaged in the lessons and were willing to do extra practice outside the classroom by going to the lab to do further exercises. Therefore, it was important to delve deeper into the matter to find out what had made the difference in their perceptions and beliefs as they had completely come out of the uneasy mode. It was also important to give them the opportunity to self-assess their articulation of the problematic sounds through recording the same sounds (i.e. /θ/, /ð/, /ŋ/, /w/, /æ/) again to help them see the progress they had made. They recorded themselves with the help of the soundforge software and realised that their articulations were much more accurate which made them feel more confident as they had become more competent.

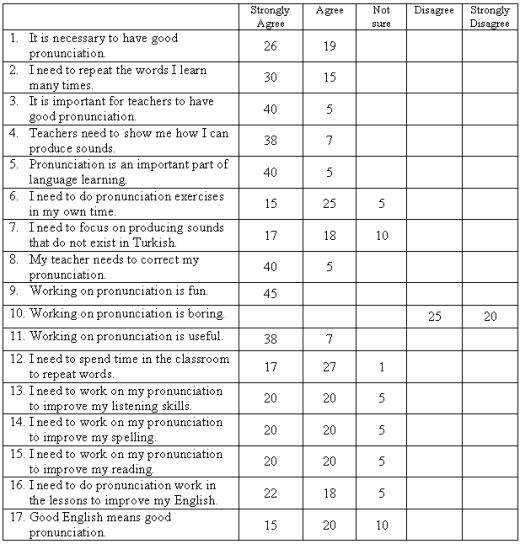

To find out the underlying reasons behind the change in their beliefs, the beliefs questionnaire was readministered and the results revealed that all the students had given positive responses to the items (please see appendix 2), which was an immediate reason to explore further through a final round of semi-structured interviews with randomly selected 15 students. The following were some of the responses students gave with respect to the change in their beliefs (translated from their responses in Turkish):

“I think I can speak better.”

“I sound and feel like a different person.”

“I can mostly understand/recognise the words I hear on TV/in movies, etc.”

“Pronunciation work has a big role in language learning.”

“Pronunciation lessons are very interesting and I don’t understand how time passes.”

“I now know that repetition is very useful”

“I started repeating the sounds I learnt when I am alone. It really helps to practice in front of the mirror!”

“Pronunciation is no more a scary movie.”

“I can pick out people’s mistakes. It really is great. I feel more confident know.”

“I now know that –w- exists in Turkish (kavun/kavuk).”

“My listening grades have become better. I wonder why?”

The following are the main findings of the study that have helped change students’ perceptions and improve their pronunciation:

- Making students realise that pronunciation is an area that most learners find difficult and that they are not the only ones feeling uneasy about it.

- Giving the responsibility to the students and letting them work in their own pace as each person is unique and therefore accepting the fact that some may need more practice than others (e.g. getting students to self-assess themselves and record their own articulations for future reference and practice, etc.)

- Building students’ confidence and making them believe that they can improve their pronunciation and that they should try hard and not give up until they get it right. Reminding them constantly that repetition/practice makes perfect!

- Showing how the sounds are articulated through diagrams/audiovisual means- muscle movements, etc. This helps them produce the sounds more easily as they can visualise the movements.

- Getting students to realise the progress they have made e.g. getting them to compare the waveforms of the sounds they have articulated with the acceptable versions. This builds their confidence and gives them a reason to try harder until they get it right.

- Resorting to reinforcement tools when teaching pronunciation (e.g. games, competitions, software to support in- class work, etc.)

- Spicing up pronunciation lessons with themes/topics that are of interest to the students always help engage students and turn it into an enjoyable experience for them.

RESULTS OF THE INITIAL ADMINISTRATION OF THE BELIEFS QUESTIONNAIRE

RESULTS OF THE FINAL ADMINISTRATION OF THE BELIEFS QUESTIONNAIRE

PRONUNCIATION LESSON FRAMEWORK

Presentation Stage (15 minutes)

- Lead-in through a story/text with the sounds to be focused on during the lesson.

- Signpost focus.

- Review necessary background knowledge.

- Presentation and practice of the corpus – drilling

- Presentation and practice of minimal pairs – drilling

Practice Stage 1 (15 minutes)

- Phrase and Clause level practice – drilling

- Focus on rule/Audiovisual representation of the sound (e.g. software, diagrams, etc.)

- Minimal sentences– drilling

- Contextual sentences – drilling

- Tongue twisters – drilling

Practice Stage 2 - Production (20 minutes)

- Tasks/Exercises/Games – built around the theme

- Wrap up

- Assignment – software exercises

Derwing, T.M. & Munro, Murray. J. (1997). Accent, Intelligibility, and Comprehensibility. Studies in Second Language Acquisition.19, 1-16.

Firth, S. (1992). Pronunciation Syllabus Design: A Question of Focus. In P. Avery & S.

Jenkins, J. (2004) "Research in teaching pronunciation and intonation", Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 24: 109-125.

Lin, H., Fan, C., & Chen, C. (1995). Teaching Pronunciation in the Learner-Centered

Classroom. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED393292)

Morley, J. (1991). The Pronunciation Component in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages. TESOL Quarterly, 25(3), 481-520.

Pennington, M. C. (1994) "Recent research in L2 phonology: Implications for practice", in Morley, J. (Ed.) Pronunciation Pedagogy and Theory: New Views, New Directions. Alexandria, VA: TESOL. pp. 92-108.

Pennington, M. C. (1996) Phonology in English Language Teaching. An International Approach. London: Longman

Scarcella, R. & Oxford, R..L. (1994). Second Language Pronunciation: State of the Art in Instruction. System. 22 (2), 221-230.

Stern, H.H. (1983). Fundamental Concepts in Language Teaching. Oxford: OUP.

Varonis, E., & Gass, S. (1982). The Comprehensibility of Nonnative Speech. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 4,114-136.

Wong, R. (1987). Teaching Pronunciation: Focus on English Rhythm and Intonation. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall Regents.

Please check the Pronunciation course at Pilgrims website.

|