From the Author

In the March 2000 issue of Humanising Language Teaching, a group of my students (Music from Naples) wrote about the effects of some odd-seeming classroom activities. I added a note to the effect that I didn’t know why or how it worked, it just did. This article is an attempt to set out the rational and offer samples of the activity types. I would be very happy to exchange ideas and materials with other teachers. One way of doing this would be to contribute to the monthly newsletter of my association for teachers, learners and speakers of English, CAMPANIA ELT. E-mail: elt@boardman.it

Creative Language Learning

Roy Boardman, Italy

Roy Boardman is a lecturer in English for International Relations at Naples University. He is interested in all aspects of language and literature teaching and teacher training. He has written coursebooks and experimental materials. His current interests are creative language teaching and learning. E-mail: royboardman@hotmail.com

Menu

Introduction: The creative nature of native speaker language

What we expect of learners

Learning through creative language use

Creative language activities

Creative language learning activities

Creative interaction activities

Conclusion

One of the characteristics of native speakers is their ability, not only to produce recognisably correct or ‘acceptable’ language and understand a wide variety of spoken and written text-types, but also to create new language acceptable to interlocutors as well as to understand and react appropriately to the neologisms of others. We adapt existing words to new circumstances, giving them wider ranges of meaning with richer associations; invent new words; find appropriate contexts for words from other languages; apply rules in cases where they have never before been applied; and generally play with language in ways which are appreciated by our listeners and readers. If this were not so, we would not only have no literature, we would have no natural, dynamic conversation. Confident creativity in language use, whether by the ‘well educated’ or the ‘less educated’, in this or that dialect, is a defining characteristic of ‘nativeness’.

But it goes further than this. Every time we say “Good morning” it is never the same “Good morning”. The words are not different, though the intonation and tone may be. It is the total context of utterance that is different, and this cannot be divorced from the words themselves any more than our arms cannot be divorced from the rest of our bodies and remain arms. The speaker’s intention, the person or people being addressed, the speaker’s knowledge and opinion of these people, the place, the time, the presuppositions … all of these are different every time the utterance is pronounced. “Good morning” could mean “You’re late”, “Sorry, I’m late”, “What a great day it is”, “I love you”, “I hate you” and so on ad infinitum. And it can, of course, mean “I wish you good morning,” but even then it is different on every occasion. In other words, while the words and structure of an utterance are deprived of meaning in the museum display case of a coursebook or recorded dialogue, every naturally occurring utterance in the context of an interaction is unique and acquires meaning through its uniqueness. Every utterance is newly-created. And this is where authentic speech differs from most classroom language. Every instance of authentic language use is a creative act, whether it contains neologisms or not. In this sense, “She’s fantastic” is as unique as “She doth make the candles to burn bright”, though no one would wish to hear the former as an appreciation of Juliet at the Capulets’ ball.

Generally speaking, we do not expect learners to develop this ability; we normally concern ourselves with enabling them to understand and produce already-existing samples, and feel gratified when they occur appropriately in our learners’ speech and writing. We may, of course, include “creative writing” in our courses, especially after, say, B2 level, but usually without expecting students to produce unusual but effective combinations of words; and in getting our students to talk, we aim at fluency, but normally without expecting much wordplay. Many of us would almost certainly be suspicious of attempts to allow learners to take risks of this kind, given that they are, in any case, taking risks all the time in their attempts to produce the language to be found in the dictionary and the grammar books. This article will suggest and recommend that we give greater attention to what is here called ‘creative language learning’, not in order to get learners to conform to static native-speaker models, but as a significant step away from the unreal and artificial EFL model of the language and towards rewarding, flexible self-expression in English.

This article will illustrate creative language learning by breaking it down into the following categories:

- activities in which students invent language, focusing on the product (creative language activities)

- activities in which students work on and use language in the mind in response to environmental stimuli, focusing on the process (creative learning activities)

- activities in which students experiment with unusual ways of interacting with spoken and written text, focusing on the changes such interaction brings about in the environment through the agency of, and including, interlocutors (creative interaction activities).

The article will recommend that such activities should be central to foreign language learning and teaching. Each activity is “creative” in that it will have a range of possible outcomes; that is, outcomes that differ from individual to individual but each equally appropriate or valuable, or a variety of outcomes from each individual. The two activities described below for each category are a sample of twenty or so in that category that I have used with students over a number of years.

Activity 1: Inventing compound nouns

| Native speaker ability: |

combining nouns to create original compound nouns which may, over time,

become norms of the language. |

| Everyday example: |

railway station |

| Literary example: |

salad days (Shakespeare, Antony and Cleopatra) |

Authentic text: Song: Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds, The Beatles

- The song you are going to hear was written and recorded in the 1960’s. It contains a lot of unusual phrases. They are all compound nouns, phrases made up of two nouns like ‘flower shop’ and ‘bus ticket’. As you listen, try to recognise and write down one compound noun.

- Read the list of 18 compound nouns. Match the unfamiliar words with the definitions.

| COMPOUND NOUNS |

DEFINITIONS |

- tangerine trees

- play station fingers

- kaleidoscope eyes

- big burger mouths

- rocking horse people

- newspaper taxis

- DVD pages

- marmalade skies

- submarine silence

- plasticine porters

- marshmallow pies

- cellophane flowers

- Internet hands

- house music fields

- Easyjet magic

- takeaway parcels

- looking glass ties

- banana split sweaters

|

- a sweet dish with bananas and ice cream

- a small sweet fruit like an orange with a skin

that comes off easily; a bright orange colour

- a jam made from fruit such as oranges,

lemons or grapefruit, usually eaten at

breakfast

- a pattern, situation or scene that is always

changing and has many details or bright

colours

- a think transparent material used for wrapping

things

- a wooden horse for children that moves

backwards and forwards when you sit on it

- a very soft light white or pink sweet, made of

sugar and egg white

- a soft substance like clay, that comes in many

different colours and is used by children for

making models

- a mirror

- a low-cost airline company

- a meal that you buy at a shop or restaurant to

eat at home

- a type of popular dance music

|

| All definitions are from the Longman |

Dictionary of Contemporary English |

- The song was written and recorded in the 1960’s. Which of the compound nouns in the list do you think are used in the song? Why?

- Listen to the song again and check your answers to 3.

- Each of the compound nouns in the song has two main stresses. Here they are. Practise saying them.

tangerine trees marmalade skies kaleidoscope eyes

cellophane flowers rocking horse people marshmallow pies

newspaper taxis plasticine porters looking glass ties

- What do these very unusual compound nouns mean? How can trees be ‘tangerine’, for example? Think about this, then discuss your interpretations with a partner.

- Here are some possible interpretations. How far do they correspond with yours? Which of them convince you, which don’t?

tangerine trees are bright orange in colour, like trees in a child’s drawing

marmalade skies are bright with some clouds, like marmalade with pieces of peel in it.

kaleidoscope eyes seem to be of many colours when they reflect the sun

cellophane flowers are flowers that are so beautiful they don’t look real

rocking horse people are people sitting cross-legged on the grass, having a picnic, so they bend backwards and forwards to pick up their sandwiches and cakes

marshmallow pies are small cakes with white and pink cream on them

newspaper taxis are taxis that arrive just where and when you want, like newspapers being delivered

plasticine porters are railway station porters in bright-coloured uniforms, standing still waiting for customers

looking glass ties are ties which are all alike, so that when the porters stand facing each other one looks like a mirror reflection of the other

- In groups, read the text of the song. Invent different compound nouns to replace the ones in the song, like this:

Picture yourself in a boat on a river

with comic-book trees and filmstar-face skies

Make sure you get the stresses right!

- Each group sings its own version of the song to the rest of the class. Take a vote on the best one.

- Imagine an exotic or unfamiliar scene which would need new or imaginative compound nouns to describe the objects in it. For example, a fairground on another planet. Describe or draw the scene, and invent three or more compound nouns to describe objects or activities that will be unfamiliar to your readers.

Activity 2: Understanding unfamiliar phrasal verbs and inventing new ones

| Native speaker ability: |

combining verbs and particles to create new phrasal verbs which other

native speakers understand and accept |

| Everyday example: |

think up |

| Internet language example: |

log out |

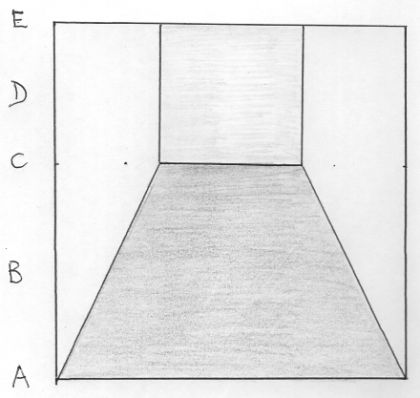

In this activity, students first attempt to identify the semantic common denominator of a particle used in seven phrasal verbs; the particle used here is up, and the same teaching/learning sequence can be used with others. They then map this common denominator onto an image or diagram which conflates the various subtle differences into a single “meaning”. They suggest what the single meaning might be as suggested by the image, and work out the meanings of seven phrasal verbs using up, try to use them, then look them up in a learner’s dictionary to see how close they are to the definition and examples. They are then given a number of frequently-occurring verbs, choose three of them to which to add up, and try them out on the teacher.

- Here is a list of 7 phrasal verbs using up (all of which you know), sentences in which they occur, and an indication of the meaning suggested by the particle. Do you agree with the meaning suggested?

| get up |

RISE/END OF PERIOD OF TIME (IN BED) |

He got up at 8 o’clock. |

| shut up |

FINISH |

Jill told Jack to shut up. |

| give up |

FINISH |

Jack gave up smoking. |

| make up |

COMPLETE |

Jill invented a story about

a hill. |

| eat up |

FINISH |

“Eat up your soup,” I said. |

| take up |

START A NEW PERIOD OF TIME |

Jack decided to take up

medicine. |

| pick up |

RISE/RAISE |

Jill picked up the bucket. |

- How does the following image express what all the uses of up have in common?

What point in the diagram (A, B, C, D or E) relates most directly to up? (C) Why? In what way do all the phrasal verbs indicate a change in situation, a passing from one point to another? How do the parts of the diagram express this?

Which of the phrasal verbs in 1. above relate most clearly to TIME? Which to SPACE? Which to ACTIVITY?

- Here are another seven phrasal verbs, They are probably all unfamiliar to you. Work out their meanings and discuss them with a partner.

| move up |

There wasn’t much standing room on the bus so she asked the person

next to her to move up. |

| catch up |

Are you already on exercise 6? How do you expect me to catch up? |

| bring up |

If you think it’s so important, bring it up at the meeting. |

| run up |

We ran up a huge electricity bill that winter. |

| wind up |

It’s an old-style clock. Don’t forget to wind it up. |

| do up |

The baby learnt to do up her coat buttons at an early age. |

| cheer up |

Perhaps another drink will cheer me up. |

- Now look up the phrasal verbs in your dictionary, read the definitions and the examples, and see how right or wrong you were.

- Choose three of the following verbs, add up to them, write dictionary definitions and an illustrative sentence for each.

- sit

- turn

- send

- beat

- end

- cut

- come

- collect

- drink

- drive

4. Try your sentences out on your teacher and look them up in the dictionary. Look up?!

Activity 1: Mapping dialogues onto intonation and stress patterns

Mapping intonation and stress meaning onto lexical and syntactic meaning is a way of simulating and stimulating one aspect of the mental process that goes into sentence formulation and production. Done on a regular basis, it can make an important contribution to the language-learning process.

- Students look at two pictures, one a picture of someone asking the way, the other of someone buying a pair of jeans in a shop.

- Students hear the teacher “hum” the intonation pattern, and tap out the stress and rhythm pattern, of the “asking the way” dialogue and are asked to identify it with one of the two pictures.

- They hear the intonation, stress and rhythm patterns of the “buying a pair of jeans” dialogue and are asked if they are sure about which situation it refers to.

- They hear the patterns again and, working individually, write dialogues corresponding as closely as possible to the patterns.

- They compare their dialogues and come to a consensus, listening to the patterns again and repeating to themselves.

The dialogues will be typical “museum showcase” examples. You can have some fun afterwards by introducing an “alien” pattern for the class to decide where it can be introduced into the dialogues, with what words and structure.

Activity 2: Mapping language onto observed situations/places/events

Students are asked to spend about 10 minutes outside the classroom, at the bus stop, the railway station or anywhere that catches their fancy, observing their surroundings and what is happening. They mentally label all the objects, people, actions with English words they know, and take a note of anything they would not be able to describe except perhaps by paraphrase. When they get home, they check what they did not know in the dictionary; and when they are next in the classroom, report to the class and to the teacher.

Students should be encouraged to do this as often, and in as many situations, as possible. It’s all about beginning to “think” in English. One good way to start, and that can be brought back into the class, is by asking them to spend half an hour in their room at home thinking – without writing . of how to name, describe, and comment on all the objects they normally surround themselves with.

This is an excellent activity for students while spending a period of time in an English-speaking country, where much of what they experience will be unfamiliar.

Activity 1: Fitting the same utterance into different communication contexts

- How many ways can we say It’s eight o’clock? Students experiment with saying it with different stress and intonation patterns, suggesting the situation in which it might occur.

- Students ask questions about possible situations in which It’s eight o’clock occurs by asking themselves questions, individually or in groups, such as:

Who said it?

Who did s/he say it to?

Where were they?

What were they thinking about?

What worries did they have?

What were they doing?

--- and so on. They invent the questions themselves until they can imagine well-defined situations.

- Each student presents his/her version in the form of a play which s/he invites a group to act out. For example (this can be the model example given by the teacher):

Robin is sitting in front of a full-length mirror, the script of a play on his lap. He mouths the words as he tries to remember them. Joyce paces up and down behind him, putting on her coat.

ROBIN: “I take thee at thy word!”

JOYCE: It’s eight o’clock.

ROBIN: We don’t have to be on stage until nine and I’ve just got to get these lines right.

JOYCE: Right, I’m off. And I hope I don’t have to imagine you’re down there in the orchard when I’m up on the balcony. I’ll throttle you if you don’t make it on time.

- The class votes on a meaning to assign to It’s eight o’clock for each situation they have invented. In the case of 3 above, it’s something like “It’s too late to be learning your words at the last moment. Hurry up!”

Notice that in this form of activity, as is characteristic of many creative interaction activities, the student begins by questioning the text, whether spoken or written. The answers to these questions produce the parameters of the communication context, and students are made aware of and sensitized to the concept of uniqueness as defined in the introduction to this article.

Activity 2: Interacting with a bare-bones text to personalize it and make it live

Students should think of all text, both spoken and written, as a feature of the world with which to interact and render richer and more rewarding, just as interaction between people creates the kind of social activity that is basic to ‘being human’. Of course, we interact with text in one way or another all the time; making it a conscious activity in language-learning contexts is a way of behaving and learning that feels natural. We are naturally creative, so that learning creatively in the sense that this article has, I hope, made clear ensures that the activities are not imposed or foreign to normal behaviour, but emanate from the individual even if tickled into being by the teacher.

The activity of interacting with a bare-bones text is based on this natural interactive process.

- Students are given a bare-bones text like the following:

It was Jack’s birthday, Jill remembered when she woke up. It was always difficult to

decide what present to give him. Then she realised what he needed. “I’ll get him that

new album he was talking about last night,” she thought.

- Students are invited to ask themselves questions about the text the answers to which are not there, so that they have to be invented. This can be done by students working individually, answering their own questions, or in pairs, with each student asking different questions so that s/he gets a different final version. Questions about the Jack and Jill text might be:

How old was Jack?

Who was Jill?

Were they in the same house that morning?

Why was it difficult to decide what presents to give him?

What kind of album was it?

Why did he need the album?

- By answering their own questions, students will create texts something like:

Jack and Jill were twins, and she knew he’d bought her a lovely birthday present.

She’s seen the beautifully-wrapped parcel in his room. It was always difficult to

decide what to buy Jack, and especially on his 18th birthday. He had all the albums

of his favourite groups because h e too was a musician. Then she remembered him

talking about the new “Black Hole Vistas” album. It was far more expensive than

most albums, and just right for a present. He wanted to use it to imitate Whacky

Miller’s style on the guitar. That’s what she’d give him!

- Students now exchange their texts for reading and comment. Each text is unique, a function of the interaction between it and the individual student.

Creative language teaching obviously overlaps with creative language learning, the difference being the focus in the latter of students’ gradual approximation, not to the native-speaker model, but to native-speaker processes whose outcome in terms of language formulated in the mind (thinking in English) and spoken and written production is unique and at times original. Creative language learning puts the emphasis on what happens in the learner’s mind and on interactions with the environment (including interlocutors in the environment) that continually modify the learner’s hypotheses about the structure and use of the language. To take this approach in teaching foreign languages demands acceptance of the positive effects of risk-taking and an avoidance of overuse of production models to be emulated.

Please check the Creative Methodology for the Classroom course at Pilgrims website.

|